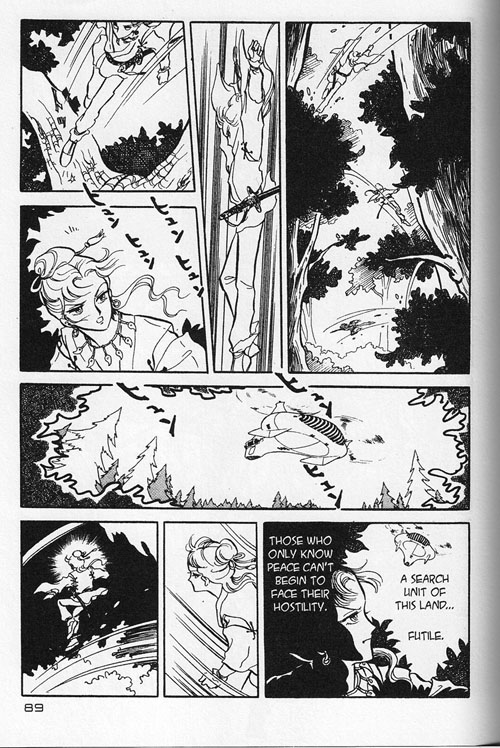

Ah, Keiko Takemiya, how I love your sci-fi extravaganzas! The psychic twins. The giant spiderbots. The evil, omniscient computers. The sand dragons. The fantastic hairdos. Just think how much more entertaining The Matrix might have been if you’d been at the helm instead of the dour, self-indulgent Wachowski Brothers! But wait… you did create your very own version of The Matrix: Andromeda Stories. Your version may not be as slickly presented as the Wachowski Brothers’, but you and collaborator Ryu Mitsuse engage the mind and heart with your tragic tale of doomed love, lost siblings, and machines so insidious that they’ll remake anything in their image—including the fish.

Ah, Keiko Takemiya, how I love your sci-fi extravaganzas! The psychic twins. The giant spiderbots. The evil, omniscient computers. The sand dragons. The fantastic hairdos. Just think how much more entertaining The Matrix might have been if you’d been at the helm instead of the dour, self-indulgent Wachowski Brothers! But wait… you did create your very own version of The Matrix: Andromeda Stories. Your version may not be as slickly presented as the Wachowski Brothers’, but you and collaborator Ryu Mitsuse engage the mind and heart with your tragic tale of doomed love, lost siblings, and machines so insidious that they’ll remake anything in their image—including the fish.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Mitsuse and Takemiya invert the normal order of events in a classical drama and begin Andromeda Stories with a wedding. A royal wedding, to be exact, forging an alliance between Cosmoralia and Ayoyoda, two kingdoms on the planet Astria. On the eve of the ceremony, newlyweds Prince Ithaca and Princess Lilia spot a mysterious blue star pulsating in the night sky. Shortly after the star’s appearance, a meteorite crashes through Astria’s atmosphere with a deadly cargo: an army of nanobots seeking human hosts. Only Il, a fierce female warrior, and Prince Milan, Lilia’s devoted brother, realize that these cyber-critters are rapidly transforming Cosmoralia’s population into a Borg-like race of automatons. Il and Milan set out to liberate Cosmoralia from the grips of this cyber-invasion force before the contagion of violence and fear spreads to Ayoyoda.

…

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society.

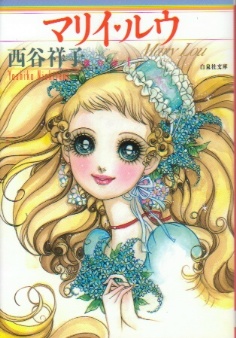

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society. In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in

In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in  The next time someone dismisses manga as a “style” characterized by youthful-looking, big-eyed characters with button noses, I’m going to hand them a copy of AX, a rude, gleeful, and sometimes disturbing rebuke to the homogenized artwork and storylines found in mainstream manga publications. No one will confuse AX for Young Jump or even Big Comic Spirits; the stories in AX run the gamut from the grotesquely detailed to the playfully abstract, often flaunting their ugliness with the cheerful insistence of a ten-year-old boy waving a dead animal at squeamish classmates. Nor will anyone confuse Yoshihiro Tatsumi or Einosuke’s outlook with the humanism of Osamu Tezuka or Keiji Nakazawa; the stories in AX revel in the darker side of human nature, the part of us that’s fascinated with pain, death, sex, and bodily functions.

The next time someone dismisses manga as a “style” characterized by youthful-looking, big-eyed characters with button noses, I’m going to hand them a copy of AX, a rude, gleeful, and sometimes disturbing rebuke to the homogenized artwork and storylines found in mainstream manga publications. No one will confuse AX for Young Jump or even Big Comic Spirits; the stories in AX run the gamut from the grotesquely detailed to the playfully abstract, often flaunting their ugliness with the cheerful insistence of a ten-year-old boy waving a dead animal at squeamish classmates. Nor will anyone confuse Yoshihiro Tatsumi or Einosuke’s outlook with the humanism of Osamu Tezuka or Keiji Nakazawa; the stories in AX revel in the darker side of human nature, the part of us that’s fascinated with pain, death, sex, and bodily functions. Reading The Times of Botchan reminded me of watching Alexander Sakurov’s cryptic 2002 film

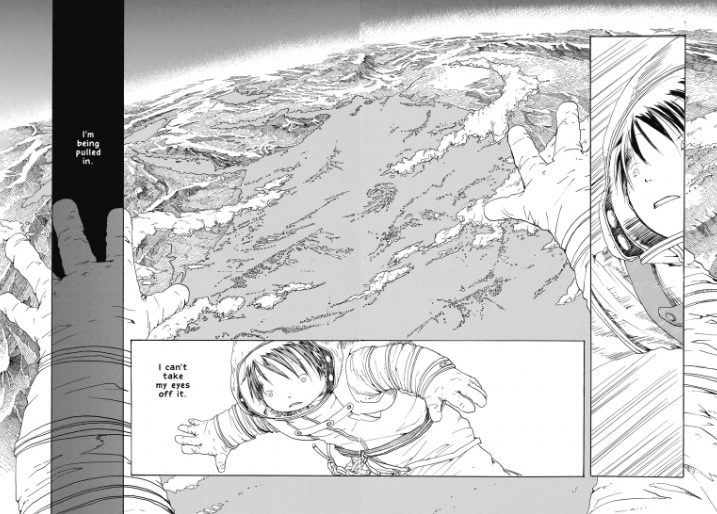

Reading The Times of Botchan reminded me of watching Alexander Sakurov’s cryptic 2002 film  If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.

If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.

The frog who appears to be a prince is a staple character in romantic comedies: what Jane Austen novel didn’t feature a handsome, wealthy suitor who, in the final pages of the story, turned out to be ethically challenged, penniless, or engaged to someone else? My Girlfriend’s a Geek offers a more up-to-the-minute version of Mr. Willoughby, this time in the form of a nice young woman who looks like a dream and holds down a responsible job, but has some rather unsavory habits of mind.

The frog who appears to be a prince is a staple character in romantic comedies: what Jane Austen novel didn’t feature a handsome, wealthy suitor who, in the final pages of the story, turned out to be ethically challenged, penniless, or engaged to someone else? My Girlfriend’s a Geek offers a more up-to-the-minute version of Mr. Willoughby, this time in the form of a nice young woman who looks like a dream and holds down a responsible job, but has some rather unsavory habits of mind. Asumi Kamogawa is a small girl with a big dream: to be an astronaut on Japan’s first manned space flight. Though she passes the entrance exam for Tokyo Space School, she faces several additional hurdles to realizing her goal, from her child-like stature — she’s thirteen going on eight — to her family’s precarious financial position. Then, too, Asumi is haunted by memories of a terrible fire that consumed her hometown and killed her mother, a fire caused by a failed rocket launch. Yet for all the pain in her young life, Asumi proves resilient, a gentle girl who perseveres in difficult situations, offers friendship in lieu of judgment, and demonstrates a preternatural awareness of life’s fragility.

Asumi Kamogawa is a small girl with a big dream: to be an astronaut on Japan’s first manned space flight. Though she passes the entrance exam for Tokyo Space School, she faces several additional hurdles to realizing her goal, from her child-like stature — she’s thirteen going on eight — to her family’s precarious financial position. Then, too, Asumi is haunted by memories of a terrible fire that consumed her hometown and killed her mother, a fire caused by a failed rocket launch. Yet for all the pain in her young life, Asumi proves resilient, a gentle girl who perseveres in difficult situations, offers friendship in lieu of judgment, and demonstrates a preternatural awareness of life’s fragility.