A Devil and Her Love Song has been one of 2012’s best surprises. Though the series uneven — and sometimes a little silly — its heroine is one of the most memorable in the Shojo Beat canon. Maria Kawai looks like a mean girl on the surface: she’s pretty and unsparingly blunt, pointing out her classmates’ insecurities with all the delicacy of Dr. Phil. Yet Maria’s bull-in-a-china-shop demeanor reflects her own uncertainty about how to be the kind of person who’s liked for who she is, not the kind of person who’s admired for telling unpleasant truths. And that makes her interesting.

A Devil and Her Love Song has been one of 2012’s best surprises. Though the series uneven — and sometimes a little silly — its heroine is one of the most memorable in the Shojo Beat canon. Maria Kawai looks like a mean girl on the surface: she’s pretty and unsparingly blunt, pointing out her classmates’ insecurities with all the delicacy of Dr. Phil. Yet Maria’s bull-in-a-china-shop demeanor reflects her own uncertainty about how to be the kind of person who’s liked for who she is, not the kind of person who’s admired for telling unpleasant truths. And that makes her interesting.

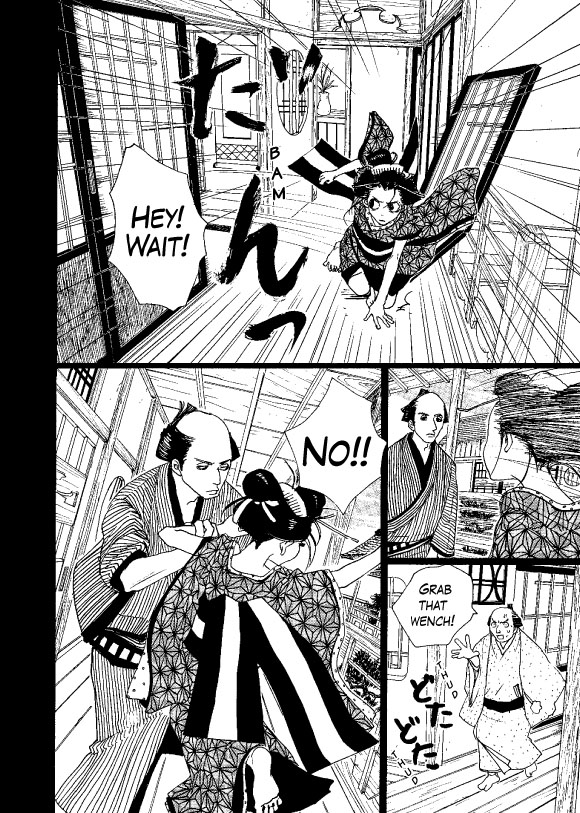

Early in volume four, for example, Maria confronts queen bee Ayu in the bathroom, where she finds Ayu primping for the television cameras. When Maria questions Ayu’s behavior — “But you look the same,” she tells Ayu — Ayu is furious. Maria, however, persists — not because she wants the embarrass a rival, but because she wants to share a hard-won piece of advice. “If someone likes you, or wants to get to know you, it’s not because of how you look,” she tells Ayu. “It’s because you show them how you feel.”

Ayu’s subsequent behavior, however, points to one of the series’ weaknesses: characters have epiphanies with whiplash-inducing frequency. (Saul would never have made it to Damascus if he fell off his donkey as many times as Maria’s classmates do.) Though some of these epiphanies feel genuine, many are contrived: would an alpha girl suddenly confess her feelings to a cute boy in front of all her friends, risking public rejection? Or the class darling admit that she’s actually a nasty manipulator, risking her popularity? Those are nice fantasies, but not very plausible ones; Tomori is working too hard to convince us that Maria’s classmates secretly wish they could be more like her, and not giving group-think and fear enough due.

The series also relies heavily on shopworn gimmicks to advance the plot. The arrival of a television crew in volume three, for example, serves no useful purpose; they disappear for long stretches at a home, only to materialize when the plot demands that someone bear witness to the class’ antics. Maria’s long-running feud with her teacher, too, feels more like an editor’s suggestion than an original idea. To be sure, a student as outspoken as Maria might infuriate a certain kind of adult, but her teacher’s cartoonish behavior renders him ineffective; his actions seem too obvious, too ripe for exposure, for him to pose a real threat to Maria.

Where A Devil and Her Love Song shines is in Maria’s one-on-one interactions with other students. These scenes remind us that everyone is wearing a mask in high school — even Maria, whose sharp comments are as much a pose as Hana’s forced cheerfulness. Though Tomori nails the mean-girl dynamic in all its exquisite awfulness, the best of these exchanges belong to Maria and Shin. Their will-they-won’t-they tension is certainly an effective narrative hook, but what makes these scenes compelling is their honesty. Tomori captures her characters’ body language and fitful conversations, which unfold in fragments, silences, and sudden bursts of feeling, rather than eloquent declarations.

I don’t know about you, but that’s how I remember high school, as a time when I had flashes of insight and bravery, but a lot more moments of cringe-inducing stupidity, cowardice, or tongue-tied helplessness. That Tomori captures adolescence in all its discomfort while still writing a romance that’s fun, readable, and sometimes endearingly silly, is proof of her skill. Now if she could just ditch the television crew and the evil teacher…

Review copy provided by VIZ Media.

A DEVIL AND HER LONG SONG • BY MIYOSHI TOMORI • VIZ MEDIA • 200 pp. • RATING: TEEN (13+)