The 1970s marked a turning point in the development of shojo manga, as the first time in the medium’s history that a significant number of women were working in the field. These “founding mothers” weren’t the first female manga artists; Machiko Hasegawa was an early pioneer with Sazae-san,[1] a comic strip that first appeared in her hometown newspaper in 1946, followed in the 1950s by such artists as Masako Watanabe, who debuted in 1952 with Suama-chan, Hideko Mizuno, who debuted in 1956 with Akakke Pony (Red-Haired Pony),[2] and Miyako Maki, who debuted in 1957 with Hahakoi Waltz (Mother’s Love Waltz). Beginning in the mid-1960s and continuing throughout the 1970s, more female creators entered the profession, thus beginning the quiet transformation of shojo manga from sentimental stories for very young readers to a vibrant medium that spoke directly to the concerns and desires of teenage girls.

Several figures played an important role in affecting this transformation. One was Osamu Tezuka, whose Princess Knight (1954)[3] is often erroneously described as “the first shojo manga.” (Shojo manga, in fact, dates to the beginning of the twentieth century, when magazines such as Shojo Sekai, or Girls’ World, featured comics alongside stories, articles, and illustrations.) An affectionate pastiche of Walt Disney, Zorro, and Takarazuka plays, Tezuka’s gender-bending story focused on a princess with two hearts — one female, one male — who becomes a masked crusader to save her kingdom from falling into the hands of a wicked nobleman. However conventional the ending seems now — Princess Sapphire eventually marries the prince of her dreams and hangs up her sword — the story was a rare example of a long-form adventure for girls; well into the 1950s, most shojo manga featured plotlines reminiscent of Victorian children’s literature, filled with young, imperiled heroines buffeted by fate until happily reunited with their families.

Another major influence was Yoshiko Nishitani, whose ground-breaking series Mary Lou appeared in Weekly Margaret in 1965. Mary Lou was among the very first shojo manga to feature an ordinary teenager as both the protagonist and romantic lead; its eponymous heroine suffered from the kind of everyday problems — a beautiful older sister, a boy who sends confusing signals — that invited readers to identify with her. Like Princess Knight, the gender politics of Mary Lou may strike contemporary Western readers as nostalgic at best, retrograde at worst, but Nishitani’s ability to make a compelling story out of ordinary adolescent experience struck a chord with Japanese girls, providing an important model for subsequent generations of shojo artists.

Moto Hagio and The “Founding Mothers” of Modern Shojo

In the hands of the Magnificent Forty-Niners and the other women who entered the field in the 1970s, shojo manga underwent a profound transformation, giving rise to a new kind of storytelling that emphasized the importance of relationships and introspection, even when the stories took place in eighteenth-century France (The Rose of Versailles), Taisho-era Japan (Haikara-san ga Toru, or, Here Comes Miss Modern), or the distant future (They Were Eleven!). Inspired by Tezuka’s cinematic approach to storytelling, they sought to dramatize their characters’ inner lives with the same dynamism that Tezuka brought to car chases, fist fights, and heated conversations. Hagio and her peers placed a premium on subjectivity, trying their utmost to help readers see the world through the characters’ point of view, eschewing tidy grids for fluid, expressionist layouts, and employing an elaborate code of visual signifiers to represent emotions from love to anxiety — symbols still in widespread use today.

Moto Hagio was one of these shojo trailblazers, making her professional debut in 1969 with “Lulu to Mimi,” a short story that appeared in the girls’ magazine Nakayoshi. In the years that followed, she proved enormously versatile, working in a variety of genres: “November Gymnasium” (1971) explores a romantic relationship between two young men, for example, while The Poe Family (1972-76) focuses on a vampire doomed to live out his existence in a teenage boy’s body. Hagio is perhaps best known to Western readers for her science fiction’s unique blend of social commentary and lyrical imagery. A, A’, for example, examines the relationship between memory and identity, while They Were Eleven tackles the thorny question of whether gender determines destiny.

A Drunken Dream and Other Stories

The ten stories that comprise A Drunken Dream span the entire length of Hagio’s career, from “Bianca” (1970), one of her first published works, to “A Drunken Dream” (1985), a sci-fi fantasy written around the same time as the stories in A, A’, to “The Willow Tree” (2007), an entry in her recent anthology Anywhere But Here.

What A Drunken Dream reveals is an author whose childhood passion for Frances Hodgson Burnett, L.M. Montgomery, and Isaac Asimov profoundly influenced the kind of stories she chose to tell as an adult. “Bianca,” for example, is a unabashedly Romantic story about artistic expression. The main narrative is framed by a discussion between Clara, a middle-aged woman, and an art collector curious about the “dryad” who appears in Clara’s paintings. As a teenager, Clara secretly witnessed her younger cousin Bianca dancing with great abandon in a wooded glen, a child’s way of coping with the pain of her parents’ tumultuous relationship. Bianca’s dance haunted Clara for years, even though their acquaintance was brief. “The way [Bianca] danced… the way it made me feel… I can’t describe it in words,” the middle-aged Clara explains to her guest. “But the thrill of that moment still shines today, and still shakes me to my core. And it was my irresistible need to draw that which led me to become a painter.”

Other stories explore the complexity of familial relationships. “Hanshin: Half-God,” for example, depicts conjoined twins with a rare medical condition that leaves one brilliant but physically deformed and the other simple but radiantly beautiful. When a life-threatening condition necessitates an operation to separate them, Yudy, the “big sister,” imagines it will liberate her from the responsibility of caring for and about Yucy, never considering the degree to which she and Yucy are emotionally interdependent. In “The Child Who Comes Home,” the emphasis is on parent-child relationships, exploring how a mother and her son cope with the death of the family’s youngest member. Throughout the story, the deceased Yuu appears in many of the panels, though we are never sure if Yuu’s ghost is real, or if his family’s lingering attachment to him is making his memory palpable.

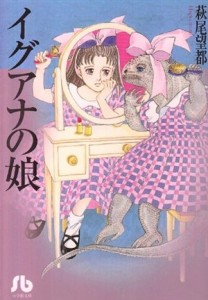

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

Perhaps the best compliment I can pay Hagio is praising her ability to make the ineffable speak through pictures, whether she’s documenting the grief that a young woman feels after aborting her baby (“Angel Mimic”) or the intense longing a middle-aged man feels for the college friends who abandoned him (“Marie, Ten Years Later”). Nowhere is this more evident than in the final story, “The Willow Tree.” At first glance, the layout is simple: each page consists of just two large, rectangular panels in which a woman stands beneath a tree, watching a parade of people — a doleful man and a little boy, a group of rambunctious grade-schoolers, a teenager wooing a classmate — as they stroll on the embankment above her. A careful reading of the images, however, reveals a complex story spanning many years. Hagio uses subtle cues — light, weather, and the principal character’s body language — to suggest the woman’s relationship to the people who walk past the tree. The last ten panels are beautifully executed; though the woman never utters a word, her face suddenly registers all the pain, joy, and anxiety she experienced during her decades-long vigil.

For those new to Hagio’s work, Fantagraphics has prefaced A Drunken Dream with two indispensable articles by noted manga scholar Matt Thorn.[4] The first, “The Magnificent Forty-Niners,” places Hagio in context, introducing her peers and providing an overview of her major publications. The second, “The Moto Hagio Interview,” is a lengthy conversation between scholar and artist about Hagio’s formative reading experiences, first jobs, and recurring use of certain motifs. Both reveal Hagio to be as complex as her stories, at once thoughtful about her own work and surprised by her success. Taken together with the stories in A Drunken Dream, these essays make an excellent introduction to one of the most literary and original voices working in comics today. Highly recommended.

A DRUNKEN DREAM AND OTHER STORIES • BY MOTO HAGIO, TRANSLATED BY MATT THORN • FANTAGRAPHICS • 288 pp.

NOTES

1. The Wonderful World of Sazae-San ran in newspapers from 1946 to 1974. The collected strips, comprising 45 volumes in all, have been perennial best-sellers in Japan, with over 60 million books sold. It’s imporant to note that Sazae-san is not shojo manga; the story focuses on a resourceful, strong-willed housewife and her family, a kind of Mother Knows Best story. Nonetheless, Machiko Hasegawa is an important figure in the history of the medium, both for the influence of her strip and her trailblazing role as a female creator.

2. For more information about Hideko Mizuno, see Marc Bernabe’s recent profile and interview at Masters of Manga.

3. Princess Knight has a long and complex publishing history. The original story appeared in Shojo Club from 1953 to 1956, was continued in Nakayoshi in 1958, and revived again for Nakayoshi in 1963. The third version is generally considered to be the definitive one; Tezuka re-worked a few details from the original version and re-drew the series. In 2001, Kodansha released a bilingual edition of the 1963 version which is now out of print.

4. Both essays originally appeared in issue no. 269 of The Comics Journal (July 2005).

FOR FURTHER READING

Bernabe, Marc. “What is the ‘Year 24 Group’?” Interview with Moto Hagio. [http://mastersofmanga.com/2010/06/hagioyear24] [Accessed 7/22/10.]

Gravett, Paul. Manga: 60 Years of Japanese Comics. New York: Collins Design, 2004.

Randall, Bill. “Three By Moto Hagio.” The Comics Journal 252 (April 2003). (Full text available online at The Comics Journal Archives.)

Shamoon, Deborah. “Revolutionary Romance: The Rose of Versailles and the Transformation of Shojo Manga.” Mechademia 2 (2007): 3-18.

Schodt, Frederick. Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics. New York: Kodansha International, 1983.

Thorn, Matt. “The Multi-Faceted Universe of Shoujo Manga.” [http://www.matt-thorn.com/shoujo_manga/colloque/index.php] (Accessed 7/21/10.)

Thorn, Matt. “What Japanese Girls Do With Manga and Why.” [http://www.matt-thorn.com/shoujo_manga/jaws/index.php] (Accessed 7/21/10/)

Toku, Masaki, ed. Shojo Manga! Girl Power! Chico, CA: Flume Press, 2005.

Vollmar, Rob. “X+X.” The Comics Journal 269 (July 2005): 134-36.

WORKS BY MOTO HAGIO AND HER PEERS (IN ENGLISH)

Aoike, Yasuko. From Eroica With Love. La Jolla, CA: CMX Manga/Wildstorm Productions, 2004 – 2010. 15 volumes (incomplete).

Ariyoshi, Kyoko. Swan. La Jolla, CA: CMX Manga/Wildstorm Productions, 2005 – 2010. 15 volumes (incomplete).

Hagio, Moto. A, A’ [A, A Prime]. Translated by Matt Thorn. San Francisco: Viz Communications, 1997. (Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 5/31/10.)

Hagio, Moto, Keiko Nishi, and Shio Sato. Four Shojo Stories. Translated by Matt Thorn. San Francisco: Viz Communications, 1996. (Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 5/31/10.)

Mitsuse, Ryu and Keiko Takemiya. Andromeda Stories. New York: Vertical, Inc., 2007. 3 volumes. (Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 5/26/10.)

Takemiya, Keiko. To Terra. New York: Vertical, Inc., 2007. 3 volumes. (Reviewed at The Manga Critic on 5/23/10.)

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

When I was fifteen and in the throes of my mope-rock obsession, I fantasized a lot about England, home to my favorite bands. I imagined London, in particular, to be a place where everyone appreciated the sartorial genius of Mary Quant, fashionable ladies accessorized every outfit with a pair of shit kickers, regular moviegoers recognized Eat the Rich as brilliant satire, and — most important of all — teenage boys appreciated girls with dry, sarcastic wits and gloomy taste in music. You can guess my disappointment when I finally visited England for the first time; not only was London dirty, expensive, and filled with tweedy-looking people who found my taste in clothing odd, many of the teenagers I met were fascinated by American pop culture, pumping me and my companions for information about — quelle horror! — LL Cool J. I could have died. Though I’ve gone through similar phases since then — Russophilia, Woody Allenomania — I’ve never been able to abandon myself to those passions in quite the same way, knowing somewhere in the back of my mind that all Muscovites weren’t soulful admirers of Shostakovich and that most book editors didn’t live in pre-war sixes on the Upper East Side.

When I was fifteen and in the throes of my mope-rock obsession, I fantasized a lot about England, home to my favorite bands. I imagined London, in particular, to be a place where everyone appreciated the sartorial genius of Mary Quant, fashionable ladies accessorized every outfit with a pair of shit kickers, regular moviegoers recognized Eat the Rich as brilliant satire, and — most important of all — teenage boys appreciated girls with dry, sarcastic wits and gloomy taste in music. You can guess my disappointment when I finally visited England for the first time; not only was London dirty, expensive, and filled with tweedy-looking people who found my taste in clothing odd, many of the teenagers I met were fascinated by American pop culture, pumping me and my companions for information about — quelle horror! — LL Cool J. I could have died. Though I’ve gone through similar phases since then — Russophilia, Woody Allenomania — I’ve never been able to abandon myself to those passions in quite the same way, knowing somewhere in the back of my mind that all Muscovites weren’t soulful admirers of Shostakovich and that most book editors didn’t live in pre-war sixes on the Upper East Side.