The characters in Solanin are suffering from what I call a “pre-life crisis”—that moment in your twenties when you realize that it’s time to join the world of adult responsibility, but you aren’t quite ready to abandon dreams of indie-rock stardom, literary genius, or artistic greatness. From a dramatic standpoint, the pre-life crisis doesn’t make the best material for a novel, graphic or otherwise, as twenty-something angst can seem trivial when compared with the vicissitudes of middle and old age. Yet Asano Inio almost pulls it off on the strength of his appealing characters and astute observations.

Solanin focuses on a quartet of twenty-somethings, each struggling to shed their collegiate persona and forge adult identities. To be sure, these characters are familiar types, working dead-end jobs, remaining in relationships out of habit, and clinging to unrealistic dreams. Yet Inio never dismisses or romanticizes their pseudo-bohemian aspirations, instead viewing these angstful young adults with a parental mixture of frankness and affection.

Early in the book, for example, a young woman (Meiko) introduces her boyfriend (Naruo) to her mother while trying to conceal the fact they live together. Inio might have milked the scene for its dramatic potential, staging a confrontation between Meiko and her mother. Yet he opts for something quieter and, frankly, truer to life: Meiko’s mother calls her daughter’s bluff, then offers the couple practical advice and encouragement. Instead of being pleased, however, Meiko is dumbfounded and embarrassed, leaving Naruo to stumble alone through an awkward conversation with her mother. What makes this scene work is Inio’s even-handedness; though we feel sympathy for Meiko — she’s genuinely afraid of upsetting her parents — we also realize that she’s disappointed that her decision to move in with Naruo hasn’t caused a scandal, a symptom of her not-quite-adult-relationship with her mother.

Solanin flounders, however, when Inio injects some drama into the proceedings. His big plot twist wouldn’t seem out of place in a deliciously overripe soap opera like NANA, but it feels too contrived for a low-key, slice-of-life story like Solanin; more frustrating still, Inio telegraphs what’s going to happen more than a chapter before that Big, Life-Changing Event, blunting its emotional impact. The book never quite regains its footing, culminating in a concert scene that’s as hokey as anything in The Commitments. Granted, that scene is beautifully executed, using wordless panels to convey the blood, sweat, and tears needed to pull off a live performance, but it feels too pat to be a satisfactory resolution to what is, in essence, a detailed character study.

I also felt ambivalent about the artwork. On the one hand, Inio draws his characters in a refreshingly soft and realistic fashion; as David Welsh noted in his 2008 review, Inio captures the transitional nature of their age through small but important visual cues: gangly limbs, baby fat still evident in their cheeks and tummies, soul patches and other “unpersuasive” attempts to grow beards and mustaches. Inio nails their body language, too, evoking his characters’ emotional and physical awkwardness as they try to forge connections. In this scene, for example, Inio’s characters can barely look one another in the eye, even though it’s evident from their conversation that each has a deep personal investment in music that s/he wants to share with the other:

On the other hand, the backgrounds sometimes look like poorly retouched clip art. Such shortcuts are common in manga, but when done poorly (as they are in a few sequences in Solanin), the resulting images look more like dioramas or collages than organic compositions. In several key scenes, the characters appear to be pasted into the picture frame, floating above their surroundings instead of actually inhabiting them, spoiling the mood and pulling me out of the moment.

Artistic and narrative shortcuts aside, I’d still recommend Solanin. Inio’s book is funny, rueful, and honest, filled with beautifully observed moments and conversations that ring true, even if it occasionally succumbs to Brat Pack cliche.

This is a revised version of a review that appeared at PopCultureShock on 11/19/2008.

If someone had told me a week ago that I’d be praising Honey Hunt, I’d have scoffed at them; I’ve never been a big fan of Miki Aihara’s work, thanks to the icky sexual politics of Hot Gimmick!, but her story about a poor little rich girl who seeks revenge on her celebrity parents turned out to be shockingly readable. It isn’t terribly original — the plot mirrors Skip Beat! in its basic outline — nor is its heroine a paradigm of strength and self-sufficiency — she weeps at least once every other chapter — but Honey Hunt is slick, fast-paced, and perfectly calibrated to appeal to a sixteen-year-old’s idea of the glamorous life.

If someone had told me a week ago that I’d be praising Honey Hunt, I’d have scoffed at them; I’ve never been a big fan of Miki Aihara’s work, thanks to the icky sexual politics of Hot Gimmick!, but her story about a poor little rich girl who seeks revenge on her celebrity parents turned out to be shockingly readable. It isn’t terribly original — the plot mirrors Skip Beat! in its basic outline — nor is its heroine a paradigm of strength and self-sufficiency — she weeps at least once every other chapter — but Honey Hunt is slick, fast-paced, and perfectly calibrated to appeal to a sixteen-year-old’s idea of the glamorous life.

If I were thirteen years old, Library Wars would be at the top of my Best Manga Ever list, as it reads like a catalog of the things I dug in my early teens: books about the future, books about women breaking into male professions, books with bickering leads who harbor secret feelings for each other. I can’t say that Library Wars works as well for me as an adult, but I can recommend it to younger female manga fans who are tired of stories about wallflowers, doormats, or fifteen-year-old girls whose primary objective is to nab a husband.

If I were thirteen years old, Library Wars would be at the top of my Best Manga Ever list, as it reads like a catalog of the things I dug in my early teens: books about the future, books about women breaking into male professions, books with bickering leads who harbor secret feelings for each other. I can’t say that Library Wars works as well for me as an adult, but I can recommend it to younger female manga fans who are tired of stories about wallflowers, doormats, or fifteen-year-old girls whose primary objective is to nab a husband.

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN

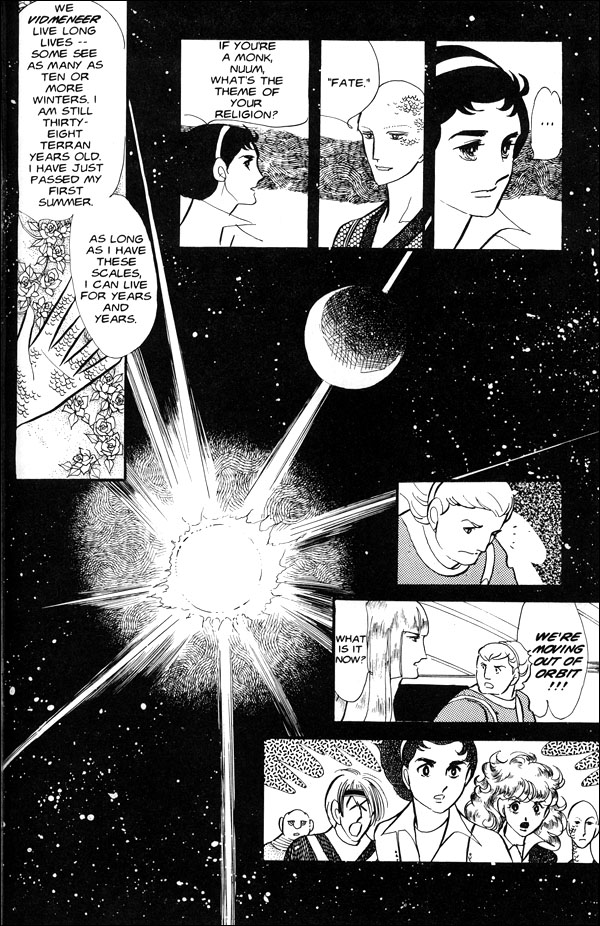

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN

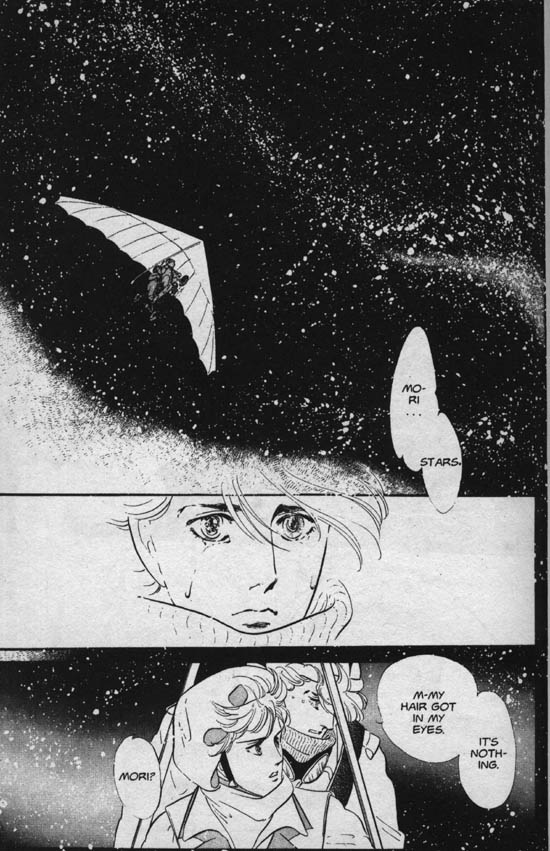

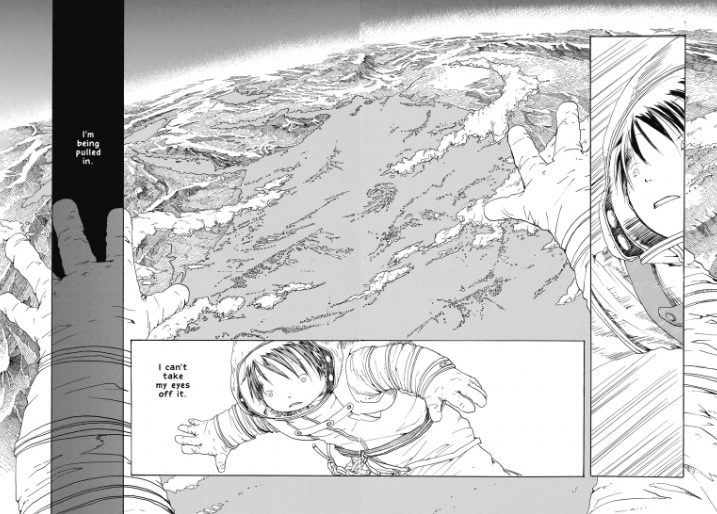

If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.

If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.

Among the most discussed scenes in the new Kick-Ass film is one that pits a tweenage assassin against a roomful of grown men. To the strains of The Banana Splits theme song, thirteen-year-old Hit Girl dispatches a dozen gangsters with a gory zest that has divided critics into two camps: those, like Richard Corliss, who found the scene shocking yet exhilarating, a purposeful, subversive commentary on superhero violence, and those, like Roger Ebert, who found it morally reprehensible, a kind of kiddie porn that exploits the character’s age for cheap thrills. What’s at issue here is not children’s capacity for violence; anyone who’s run the gauntlet of a junior high cafeteria or cranked out an essay on Lord of the Flies is painfully aware that kids can be beastly when the grown-ups aren’t looking. The real issue is that Hit Girl seems to be enjoying herself, raising the far more uncomfortable question of how children understand and wield power.

Among the most discussed scenes in the new Kick-Ass film is one that pits a tweenage assassin against a roomful of grown men. To the strains of The Banana Splits theme song, thirteen-year-old Hit Girl dispatches a dozen gangsters with a gory zest that has divided critics into two camps: those, like Richard Corliss, who found the scene shocking yet exhilarating, a purposeful, subversive commentary on superhero violence, and those, like Roger Ebert, who found it morally reprehensible, a kind of kiddie porn that exploits the character’s age for cheap thrills. What’s at issue here is not children’s capacity for violence; anyone who’s run the gauntlet of a junior high cafeteria or cranked out an essay on Lord of the Flies is painfully aware that kids can be beastly when the grown-ups aren’t looking. The real issue is that Hit Girl seems to be enjoying herself, raising the far more uncomfortable question of how children understand and wield power.