I enjoyed the first series in this franchise, Alice in the Country of Hearts, but didn’t care for Alice in the Country of Clover at all. Fortunately this variation seems much closer to the original series in tone and execution. It is the unstable April season in the Country of Hearts and a circus headed by a new character named Joker has just arrived.

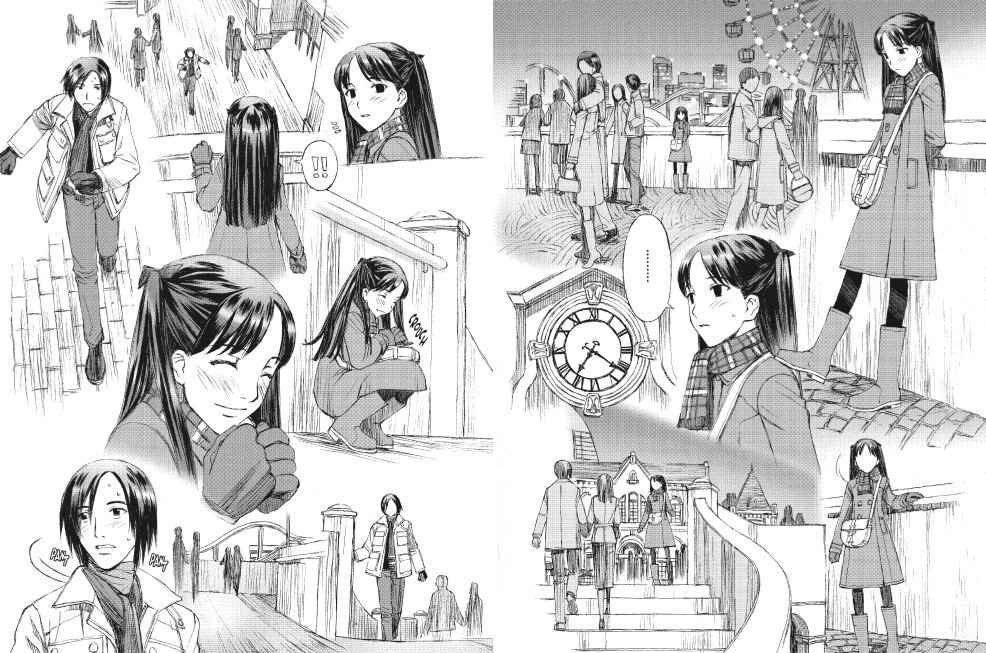

Alice seems to be having issues with both her memory and perception, aided by some mental meddling from Nightmare. Her occasional fugue states and general confusion serve to give this manga a hint of the sinister and mysterious atmosphere that I enjoyed so much in Alice in the Country of Hearts. Plotwise, there isn’t much going on as Alice goes around during April season saying hello to all the handsome male residents of Wonderland. We do get some world building bits when we see that Alice’s desires are creating a situation where there are more people with “roles” for her to interact with and there’s some nice back story filled in where we see glimpses of Alice’s life before Wonderland. There’s even a glimpse of the man from Alice’s past who is strikingly similar to the Mad Hatter but in some ways the flashback to Alice’s real life seems just as surreal as her dream world. Even though this volume is mostly exposition and getting reacquainted with most of the characters, I was curious to see how this version of the story would play out. After reading the first volume of Alice in the Country of Clover, I was wondering if any of the sequel series would appeal to me at all, but I am now wavering. Recommended for people who enjoyed the first series in this franchise.