To celebrate the release of Moto Hagio’s The Poe Clan, Shojo & Tell host Ashley MacDonald invited me to join her for an in-depth conversation about three of my all-time favorite manga: A, A’, They Were Eleven, and A Drunken Dream and Other Stories. We mulled over plot developments, discussed problematic passages, and agreed that “Iguana Girl” may be the biggest tear-jerker in the Hagio canon. (Seriously–I can’t read it without getting the sniffles.) Ashley just posted the episode, which you can check out here:

For more insight into the manga that we discussed, I recommend the following essays and reviews from The Manga Critic vault:

- The Poe Clan, Vol. 1

- A Drunken Dream and Other Stories

- Manga Artifacts: A, A’ and They Were Eleven

- An Introduction to Keiko Takemiya’s To Terra (essay explores Takemiya’s work in the context of the shojo manga revolution of the 1960s and 1970s)

I want to thank Ashley for the opportunity to chat about Hagio, and for doing such a terrific job of editing our conversation! If you’re not regularly following Shojo & Tell, I encourage you to check out the archive, as Ashley is a thoughtful host with a knack for choosing great manga and great guests. Recent contributors include Aisha Soleil and Rose Bridges discussing Bisco Hatori’s Ouran High School Host Club, Asher Sofman discussing CLAMP’s Tokyo Bablyon, and Manga Bookshelf’s own Anna Neatrour discussing Meca Tanaka’s The Young Master’s Revenge. Go, listen!

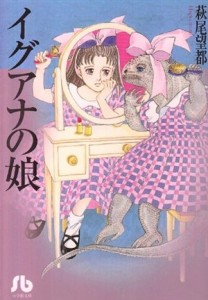

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal. The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal. 10. ASTRAL PROJECT

10. ASTRAL PROJECT 9. CHIKYU MISAKI

9. CHIKYU MISAKI 8. THE NAME OF THE FLOWER

8. THE NAME OF THE FLOWER 7. SHIRLEY

7. SHIRLEY 6. KIICHI AND THE MAGIC BOOKS

6. KIICHI AND THE MAGIC BOOKS 5. PRESENTS

5. PRESENTS 4. GON

4. GON 3. FROM EROICA WITH LOVE

3. FROM EROICA WITH LOVE 2. SWAN

2. SWAN 1. EMMA

1. EMMA 10. Astral Project

10. Astral Project 9. Chikyu Misaki

9. Chikyu Misaki 8. The Name of the Flower

8. The Name of the Flower 7. Shirley

7. Shirley 6. Kiichi and the Magic Books

6. Kiichi and the Magic Books 5. Presents

5. Presents 4. Gon

4. Gon 3. From Eroica with Love

3. From Eroica with Love 2. Swan

2. Swan 1. Emma

1. Emma A, A’ [A, A Prime]

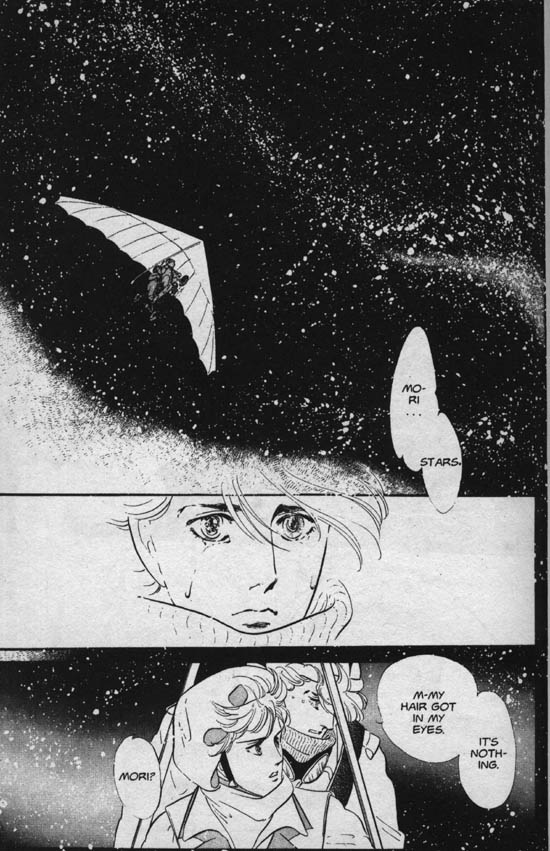

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

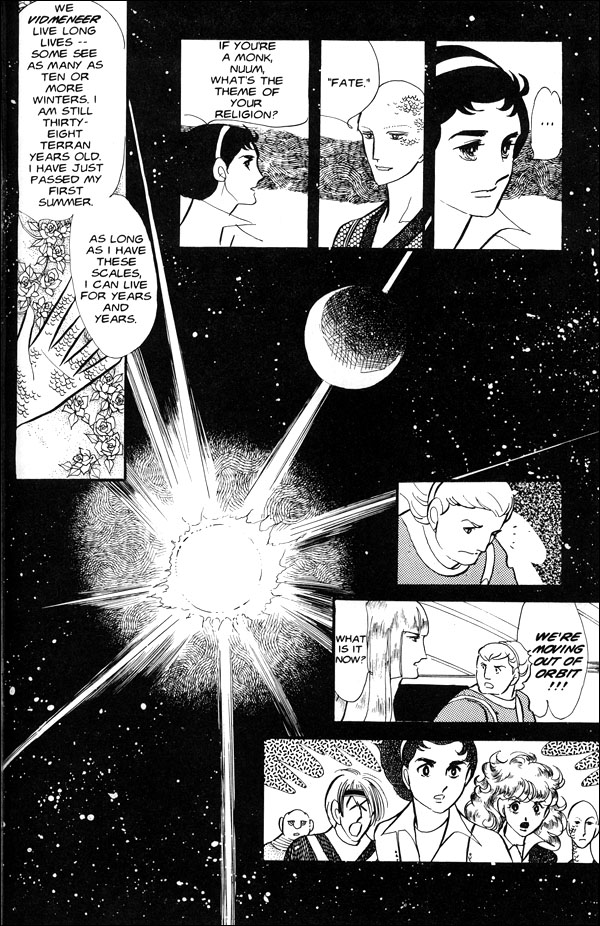

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN

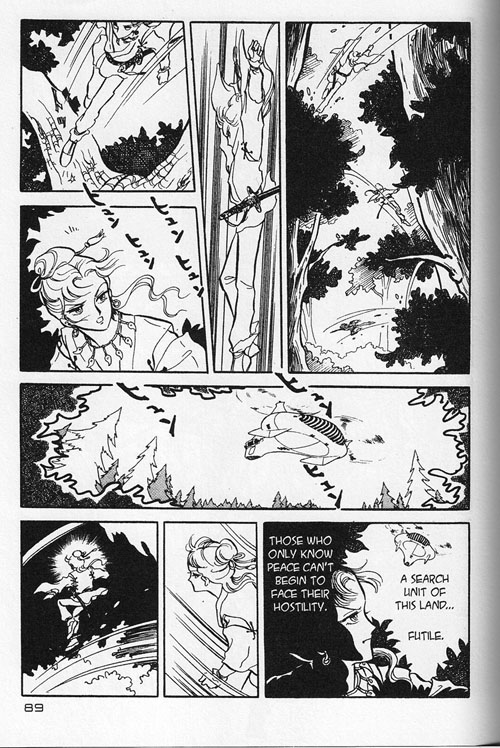

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society.

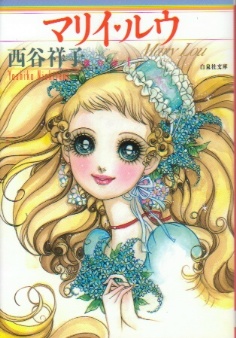

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society. In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in

In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in