When I was applying to college, my guidance counselor encouraged me to make a list of amenities that my dream school would have — say, a first-class orchestra or a bucolic New England setting. It never occurred to me to add “pet-friendly dormitories” to that list, but reading Yuji Iwahara’s Cat Paradise makes me wish I’d been a little more imaginative in my thinking. The students at Matabi Academy, you see, are allowed to have cats in the dorms, a nice perk that has a rather sinister rationale: cats play a vital role in defending the school against Kaen, a powerful demon who’s been sealed beneath its library for a century.

Yumi Hayakawa, the series’ plucky heroine, is blissfully unaware of Kaen’s existence when she and her beloved pet Kansuke enroll at Matabi Academy. Within hours of their arrival, however, they find themselves face-to-face with a blood-thirsty demon who describes himself as “the right knee” of Kaen. (N.B. He’s a lot more badass than “right knee” might suggest, and has a coat of human skulls to prove it.) The ensuing battle reveals that the school’s six-member student council is, in fact, comprised of magically-enhanced warriors who fight in concert with their pets. Each Guardian has a different ability; some possess super-strength, while others transform their cats into powerful weapons. Though prophecy foretold only six “fighting pairs,” Yumi and Kansuke quickly discover that they, too, have similar powers that obligate them to fight alongside the Guardians. Iwahara hasn’t explained why the prophecy proved wrong — a cloudy crystal ball, perhaps? — but it’s a safe bet that Yumi and Kansuke will have a special role to play in the impending showdown with Kaen, who has yet to materialize.

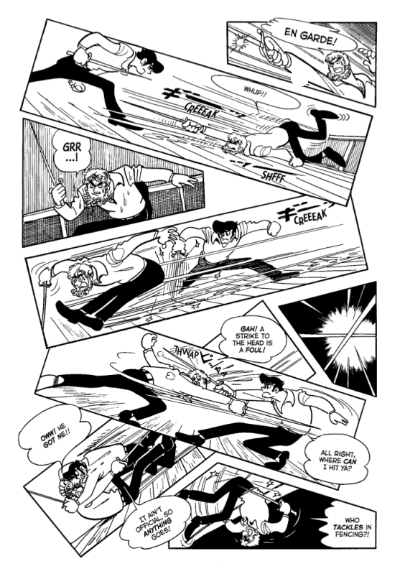

Though the plot sounds like an amalgam of manga cliches, Cat Paradise proves fun and fresh, thanks to Iwahara’s rich imagination and wicked sense of humor. The Guardians’ powers are handled in a particularly droll fashion: each student’s ability is based on his best talent, whether that be great physical speed or the ability to make a mean dumpling. The scenes in which Yumi and the other Guardians unleash their powers are both hilarious and horrifying, as Iwahara pokes fun at fighting-pair manga (e.g. Loveless) while punctuating the action with scary, visceral images (e.g. the demon’s coat). Iwahara also milks the talking animal concept for all its humorous potential, giving each Guardian’s cat a distinctive voice. The jokes are predictable but amusing; Kansuke speaks for many cats when he voices disdain for sweaters.

At first glance, Iwahara’s artwork looks a lot like other manga-ka’s. His cast is filled with familiar types, from the bishonen who’s so pretty people mistake him for a girl to the steely female fighter who looks older and more worldly than her peers. Yet a closer inspection of Iwahara’s drawing reveals a much higher level of craftsmanship that his generic character designs might suggest; he’s a consummate draftsman, favoring intricate linework over screentone to create volume and depth. (Even his character designs are more distinctive than they initially appear, as each human’s face contains a subtle echo of his cat’s.) The story’s good-vs-evil theme is neatly underscored by Iwahara’s use of white spaces and bold, black patches to create strong visual contrast and menacing shadows.

I’d be the first to admit that Cat Paradise defies easy classification. Is it a parody? A horror story? A plea for greater human-cat understanding? Or just a goof on Iwahara’s part, as his afterword suggests? No matter. Iwahara demonstrates that he can make almost any story work, no matter how ridiculous the premise may be. The proof is in the pudding: you don’t need to have a special fondness for cats, manga about cats, or manga about teen demon fighters to enjoy Cat Paradise, just a good sense of humor and a good imagination.

CAT PARADISE, VOL. 1 • BY YUJI IWAHARA • YEN PRESS • 192 pp. • RATING: OLDER TEEN

Black Cat is the story of Train Heartnet, who used to work as an assassin for a powerful organization called Chronos. After an encounter with a female bounty hunter (a.k.a. sweeper) named Saya (whom we only glimpse near the end of volume two), his outlook changed and he gave up that life. Now it’s two years later and Train has become a sweeper himself, collecting bounties on criminals with his partner, Sven. Train’s motto is “more money, more danger… more fun!” and his pursuit of the latter two usually means the duo doesn’t get much of the former.

Black Cat is the story of Train Heartnet, who used to work as an assassin for a powerful organization called Chronos. After an encounter with a female bounty hunter (a.k.a. sweeper) named Saya (whom we only glimpse near the end of volume two), his outlook changed and he gave up that life. Now it’s two years later and Train has become a sweeper himself, collecting bounties on criminals with his partner, Sven. Train’s motto is “more money, more danger… more fun!” and his pursuit of the latter two usually means the duo doesn’t get much of the former.