In the introduction to The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga, author Helen McCarthy argues that Tezuka’s work merits scholarly attention, but also deserves a more accessible treatment as well, one that acknowledges that Tezuka “was first and foremost a maker of popular entertainment.” Her desire to bring Tezuka’s work to a wider audience of anime and manga fans is reflected in every aspect of the book’s execution, from its organization — she divides her chapters into short, one-to-three page subsections, each generously illustrated with full-color plates — to its coffee-table book packaging.

As one might expect from such an ambitious undertaking, the results are a little uneven. The strongest chapters focus on the unique aspects of Tezuka’s work, exploring a variety of creative issues in straightforward, jargon-free language. McCarthy provides a helpful overview of Tezuka’s “star system” (a.k.a. recurring figures such as Acetylene Lamp and Zephyrus) and traces the evolution of his storytelling technique through dozens of series, debunking the notion that he “invented” cinematic comics while carefully spelling out what was innovative about his manga. McCarthy also makes a persuasive case for Astro Boy as one of the most important works in the Tezuka canon, the series that most clearly anticipated his mature style.

As a biography, however, The Art of Osamu Tezuka offers little insight into Tezuka’s personality beyond his relentless perfectionism and strong work ethic. McCarthy’s attempts to situate Tezuka’s work within the context of his life and times feel glib — a pity, as she makes some thought-provoking observations about Tezuka’s recurring use of certain motifs — especially androgyny, childhood, and disguise — that beg further elucidation.

That said, The Art of Osamu Tezuka largely succeeds in its mission to educate fans about Tezuka’s work process and artistic legacy, clarifying his place in Japanese popular culture, exploring his animated oeuvre, and introducing readers to dozens of untranslated — and sometimes obscure — series. A worthwhile addition to any serious manga reader’s library.

The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga

By Helen McCarthy

Abrams Comic Art, 272 pp.

House of Five Leaves, too, focuses less on Big Events and more on everyday activity, but in Leaves, Ono’s restraint serves an important dramatic purpose: she’s showing us events through Masanosuke’s eyes, as he tries to reconcile the bandits’ seemingly ordinary lives with their extraordinary behavior. Making the reader‘s task more difficult is that Masanosuke isn’t very astute. He tends to focus on a kind gesture or a friendly conversation, missing many of the important aural and visual cues that might enable him to understand what’s happening — a trait that the group exploits. In one chapter, for example, Yaichi encourages Masanosuke to accept a job as a bodyguard for a merchant family while the group plans its next kidnapping. Masa befriends his new employer’s son, never realizing that his true assignment is to infiltrate the target’s household so that Yaichi’s minions can snatch the boy for ransom.

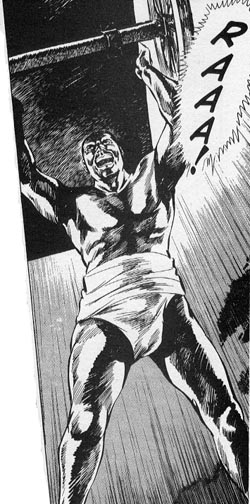

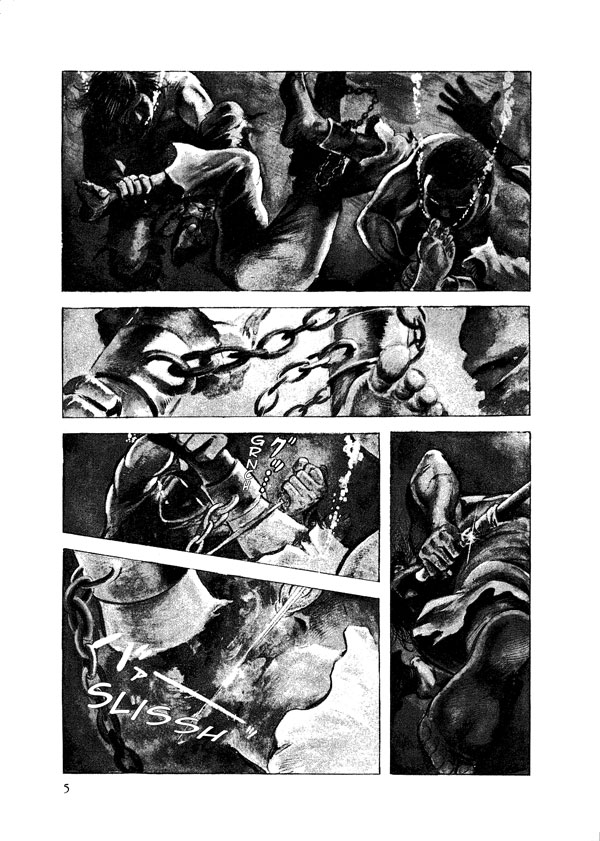

House of Five Leaves, too, focuses less on Big Events and more on everyday activity, but in Leaves, Ono’s restraint serves an important dramatic purpose: she’s showing us events through Masanosuke’s eyes, as he tries to reconcile the bandits’ seemingly ordinary lives with their extraordinary behavior. Making the reader‘s task more difficult is that Masanosuke isn’t very astute. He tends to focus on a kind gesture or a friendly conversation, missing many of the important aural and visual cues that might enable him to understand what’s happening — a trait that the group exploits. In one chapter, for example, Yaichi encourages Masanosuke to accept a job as a bodyguard for a merchant family while the group plans its next kidnapping. Masa befriends his new employer’s son, never realizing that his true assignment is to infiltrate the target’s household so that Yaichi’s minions can snatch the boy for ransom. The bigger problem, however, is that King entertains notions of race, class, and gender that would have been as alien to American colonists as they were to Japanese farmers and overlords. His blind commitment to addressing inequality wherever he encounters it — on the road, at a brothel — leads him to do and say incredibly reckless things that require George’s boffo swordsmanship and insider knowledge of the culture to rectify. If anything, King’s idealism makes him seem simple-minded in comparison with George, who comes across as far more worldly, pragmatic, and clever. I’m guessing that Koike thought he’d created an honorable character in King without realizing the degree to which stereotypes, good and bad, informed the portrayal. In fairness to Koike, it’s a trap that’s ensnared plenty of American authors and screenwriters who ought to know that the saintly black character is as clichéd and potentially offensive a stereotype as the most craven fool in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. By relying on American popular entertainment for his information on slavery, however, Koike falls into the very same trap, inadvertently resurrecting some hoary racial and sexual tropes in the process.

The bigger problem, however, is that King entertains notions of race, class, and gender that would have been as alien to American colonists as they were to Japanese farmers and overlords. His blind commitment to addressing inequality wherever he encounters it — on the road, at a brothel — leads him to do and say incredibly reckless things that require George’s boffo swordsmanship and insider knowledge of the culture to rectify. If anything, King’s idealism makes him seem simple-minded in comparison with George, who comes across as far more worldly, pragmatic, and clever. I’m guessing that Koike thought he’d created an honorable character in King without realizing the degree to which stereotypes, good and bad, informed the portrayal. In fairness to Koike, it’s a trap that’s ensnared plenty of American authors and screenwriters who ought to know that the saintly black character is as clichéd and potentially offensive a stereotype as the most craven fool in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. By relying on American popular entertainment for his information on slavery, however, Koike falls into the very same trap, inadvertently resurrecting some hoary racial and sexual tropes in the process.

Orange Planet, Vol. 1

Orange Planet, Vol. 1 Red Hot Chili Samurai, Vol. 1

Red Hot Chili Samurai, Vol. 1 Togainu no Chi, Vol. 1

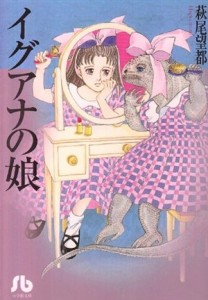

Togainu no Chi, Vol. 1  The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.