Back in the 1980s and 1990s, before publishers realized that they could sell manga to teenagers through Borders and Books-A-Million, VIZ and Dark Horse actively courted the comic-store crowd with blood, bullets, and boobs. It was a golden age for manly-man manga — think Crying Freeman and Hotel Harbor View — but it was also a period in which publishers licensed some bad stuff. And when I say “bad stuff,” I mean it: I’m talking ham-fisted dialogue, eyeball-bending artwork, and kooky storylines that defy logic. Lycanthrope Leo (1997), an oddity from the VIZ catalog, is one such manga, a horror story with a plot that might best be described as Teen Wolf meets The Island of Dr. Moreau with a dash of WTF?!

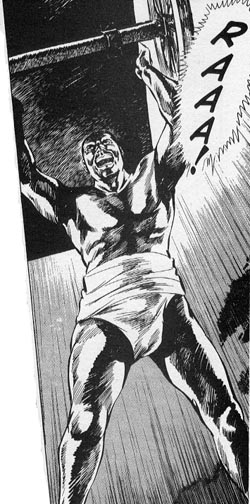

The Leo of the title is Leo Takizawa, a high school student with a cute girlfriend and a gruff father. In the days leading up to his seventeenth birthday, he surprises his track teammates with an astonishing, world-record performance in the hundred-meter dash. Dad, noticing Leo’s dramatic transformation from speedy string-bean to Carl Lewis challenger, realizes that his worst fear is coming true: Leo is on the verge of turning into a lycanthrope, a powerful shape-shifter capable of rending a man limb from limb. So Dad does what all caring, self-respecting parents in his situation would do: he lures his son into an abandoned cabin in the woods, then attempts to shoot him with a fancy crossbow — but not before he gives a long, impassioned speech explaining what Leo is and why lycanthropes are mankind’s avowed enemy. Dad’s garrulousness proves his undoing; like so many villains, he spends too much time delivering an expository monologue and not enough time getting down to business, thus providing Leo opportunity to assume his true form and take Dad out with one blow of his werelion’s paw.

Yes, you read that right: Leo is a werelion. I admit the idea has potential; it liberates the author Kengo Kaji from the conventions of Western were-lore — the silver bullets and full moons and gypsies — while allowing him to milk the human/animal dichotomy for its full dramatic potential. Alas, Kaji extends the were-concept to other, less majestic animals for a subplot involving a centuries-old conflict between carnivore and herbivore lycanthropes. (The meat-eaters favor wiping out mankind; the cud-chewers prefer peaceable co-existence.) The nadir of the anything-is-more-awesome-in-were-form, however, is Mayuko Asuka, a sexy young teacher who turns out to be… a were-flying squirrel. And an evil were-flying squirrel, I might add, one who isn’t above seducing a seventeen-year-old or attacking a lycanthrope who threatens to reveal too much of the carnivores’ world-domination plans.

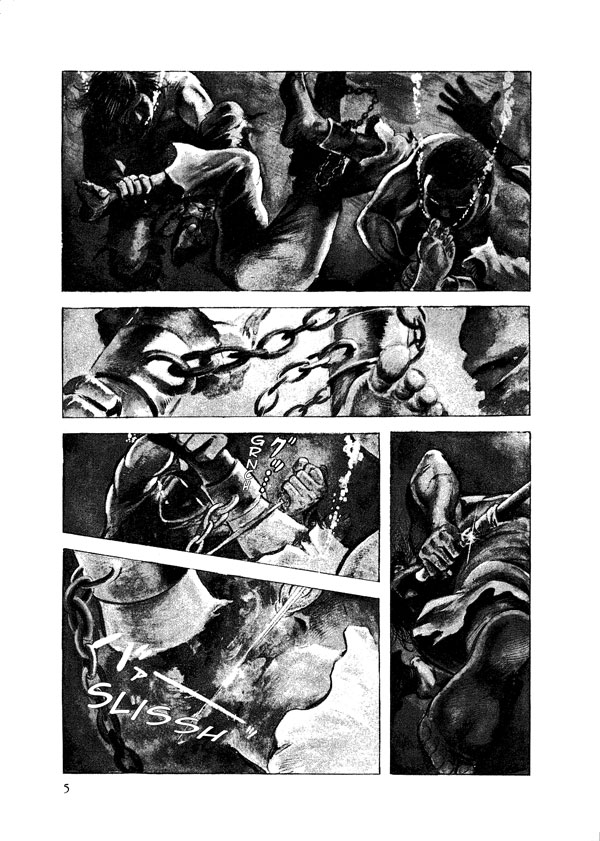

Kenji Okamura’s artwork is awe-inspiring and awful simultaneously. On the one hand, he draws amazingly detailed monsters, rendering their fur and claws and muscle-bound chests with exquisite care, even when they’re ripping each other to pieces; imagine Sylvester Stallone in werewolf drag, and you have some idea of what the male lycanthropes look like in their animal forms. On the other hand, Okamura’s human characters look like they belong in a Fernand Léger painting, with their plastic, impassive faces. Okamura struggles to convey emotion convincingly; about the best he can do is depict Leo sweating profusely. (By my count, Leo loses twenty to thirty pounds of water weight over the course of the first volume.) Worse still, Okamura frames almost every scene from an odd vantage point that distorts the characters’ anatomy, making them look ridiculously stumpy or leggy; I honestly thought Leo was being bullied by a midget in several scenes, thanks to the extreme angle at which we view Leo’s tormentor.

If you’re wondering why you haven’t heard more about Lycanthrope Leo, that’s because VIZ suspended production on the series after just one volume, citing poor sales. It’s not hard to imagine why Leo didn’t connect with American readers; the art has a throwback-to-the-eighties look, while the story is so preposterous and self-serious that it doesn’t work as straight horror or camp. From a reader’s standpoint, the most disappointing thing about Leo is the abruptness with which the English edition ends; Kaji introduces a key character in the final chapters of volume one, leaving readers to wonder whether the carnivores and herbivores eventually achieve detente. Of course, you probably won’t care if they do, considering all the sweaty, frantic silliness that precedes the introduction of the wise were-buffalo; for all the howling and “unsheathing of steel claws,” Lycanthrope Leo is about as scary as a kitten.

Manga Artifacts is a monthly feature exploring older, out-of-print manga published in the 1980s and 1990s. For a fuller description of the series’ purpose, see the inaugural column.

LYCANTHROPE LEO, VOL. 1 • STORY BY KENGO KAJI, ART BY KENJI OKAMURA • VIZ COMMUNICATIONS • 224 pp. • NO RATING (GRAPHIC VIOLENCE, NUDITY, STRONG LANGUAGE)

When reading historical manga, I grant the artist creative license to tell a story that evokes the spirit of an age rather than its details. What rankles my inner historian, however, are the kind of anachronisms that result from sheer laziness or paucity of imagination: modern slang, gross disregard for well-established fact. Alas, Color of Rage is filled with the kind of historical howlers that would make C. Vann Woodward or Leon Litwack gnash their teeth in despair.

When reading historical manga, I grant the artist creative license to tell a story that evokes the spirit of an age rather than its details. What rankles my inner historian, however, are the kind of anachronisms that result from sheer laziness or paucity of imagination: modern slang, gross disregard for well-established fact. Alas, Color of Rage is filled with the kind of historical howlers that would make C. Vann Woodward or Leon Litwack gnash their teeth in despair. The bigger problem, however, is that King entertains notions of race, class, and gender that would have been as alien to American colonists as they were to Japanese farmers and overlords. His blind commitment to addressing inequality wherever he encounters it — on the road, at a brothel — leads him to do and say incredibly reckless things that require George’s boffo swordsmanship and insider knowledge of the culture to rectify. If anything, King’s idealism makes him seem simple-minded in comparison with George, who comes across as far more worldly, pragmatic, and clever. I’m guessing that Koike thought he’d created an honorable character in King without realizing the degree to which stereotypes, good and bad, informed the portrayal. In fairness to Koike, it’s a trap that’s ensnared plenty of American authors and screenwriters who ought to know that the saintly black character is as clichéd and potentially offensive a stereotype as the most craven fool in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. By relying on American popular entertainment for his information on slavery, however, Koike falls into the very same trap, inadvertently resurrecting some hoary racial and sexual tropes in the process.

The bigger problem, however, is that King entertains notions of race, class, and gender that would have been as alien to American colonists as they were to Japanese farmers and overlords. His blind commitment to addressing inequality wherever he encounters it — on the road, at a brothel — leads him to do and say incredibly reckless things that require George’s boffo swordsmanship and insider knowledge of the culture to rectify. If anything, King’s idealism makes him seem simple-minded in comparison with George, who comes across as far more worldly, pragmatic, and clever. I’m guessing that Koike thought he’d created an honorable character in King without realizing the degree to which stereotypes, good and bad, informed the portrayal. In fairness to Koike, it’s a trap that’s ensnared plenty of American authors and screenwriters who ought to know that the saintly black character is as clichéd and potentially offensive a stereotype as the most craven fool in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. By relying on American popular entertainment for his information on slavery, however, Koike falls into the very same trap, inadvertently resurrecting some hoary racial and sexual tropes in the process.

Though I frequently grouse about fanservice , I have a grudging respect for those artists who make costume failures, panty shots, and general shirtlessness play essential roles in advancing their plots. Consider

Though I frequently grouse about fanservice , I have a grudging respect for those artists who make costume failures, panty shots, and general shirtlessness play essential roles in advancing their plots. Consider  ORANGE PLANET, VOL. 1

ORANGE PLANET, VOL. 1 Orange Planet, Vol. 1

Orange Planet, Vol. 1 Red Hot Chili Samurai, Vol. 1

Red Hot Chili Samurai, Vol. 1 Togainu no Chi, Vol. 1

Togainu no Chi, Vol. 1  ES: ETERNAL SABBATH, VOLS. 1-8

ES: ETERNAL SABBATH, VOLS. 1-8 Move over, Chucky — there’s a new doll in town.

Move over, Chucky — there’s a new doll in town.

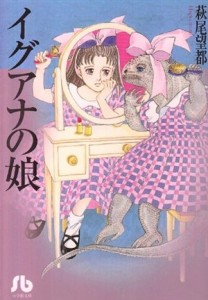

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal. The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal. When I was fifteen and in the throes of my mope-rock obsession, I fantasized a lot about England, home to my favorite bands. I imagined London, in particular, to be a place where everyone appreciated the sartorial genius of Mary Quant, fashionable ladies accessorized every outfit with a pair of shit kickers, regular moviegoers recognized Eat the Rich as brilliant satire, and — most important of all — teenage boys appreciated girls with dry, sarcastic wits and gloomy taste in music. You can guess my disappointment when I finally visited England for the first time; not only was London dirty, expensive, and filled with tweedy-looking people who found my taste in clothing odd, many of the teenagers I met were fascinated by American pop culture, pumping me and my companions for information about — quelle horror! — LL Cool J. I could have died. Though I’ve gone through similar phases since then — Russophilia, Woody Allenomania — I’ve never been able to abandon myself to those passions in quite the same way, knowing somewhere in the back of my mind that all Muscovites weren’t soulful admirers of Shostakovich and that most book editors didn’t live in pre-war sixes on the Upper East Side.

When I was fifteen and in the throes of my mope-rock obsession, I fantasized a lot about England, home to my favorite bands. I imagined London, in particular, to be a place where everyone appreciated the sartorial genius of Mary Quant, fashionable ladies accessorized every outfit with a pair of shit kickers, regular moviegoers recognized Eat the Rich as brilliant satire, and — most important of all — teenage boys appreciated girls with dry, sarcastic wits and gloomy taste in music. You can guess my disappointment when I finally visited England for the first time; not only was London dirty, expensive, and filled with tweedy-looking people who found my taste in clothing odd, many of the teenagers I met were fascinated by American pop culture, pumping me and my companions for information about — quelle horror! — LL Cool J. I could have died. Though I’ve gone through similar phases since then — Russophilia, Woody Allenomania — I’ve never been able to abandon myself to those passions in quite the same way, knowing somewhere in the back of my mind that all Muscovites weren’t soulful admirers of Shostakovich and that most book editors didn’t live in pre-war sixes on the Upper East Side.