The Red Snake isn’t the most disturbing manga I’ve read — that honor belongs to Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show, a book so intent on celebrating taboo behavior that I was certain I’d be arrested for having a copy in my house. But The Red Snake earns a special place on my manga-reading list for being one weirdest horror stories I’ve read, a grim fable about a family obsessed with bugs, boils, chickens, and snakes.

The Red Snake isn’t the most disturbing manga I’ve read — that honor belongs to Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show, a book so intent on celebrating taboo behavior that I was certain I’d be arrested for having a copy in my house. But The Red Snake earns a special place on my manga-reading list for being one weirdest horror stories I’ve read, a grim fable about a family obsessed with bugs, boils, chickens, and snakes.

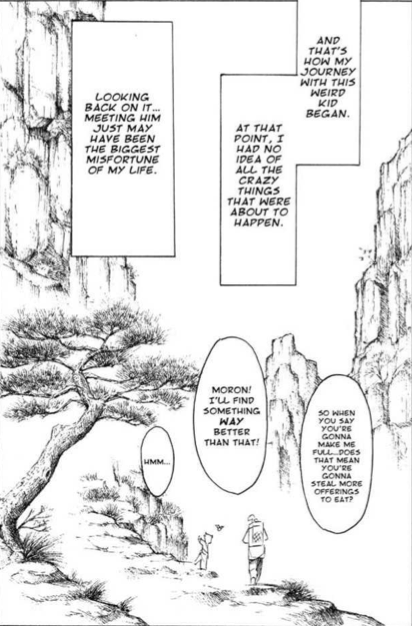

The book opens with the narrator wandering the halls of a sprawling house. “For as long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to get away from this house,” he explains. “Something evil lurks within these walls.” As lugubrious as the corridors and empty rooms may be, the inhabitants are even scarier: the grandfather is a tyrant who lavishes more attention on his poultry than on his family; the grandmother believes she’s a chicken and sits on a gigantic nest, attacking anyone who threatens her “territory”; the sister has an almost erotic fascination with insects; and the mother is a virtual slave, forced each day to massage and drain the pus from an enormous boil on the grandfather’s face. (Perhaps they’re the kind of people Tolstoy had in mind when he famously opined that “every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”?)

What follows the prologue is hard to classify as a story; it’s more a string of loosely connected vignettes, all increasingly horrific, in which:

- Snakes violate the sister in almost every way imaginable;

- The sister kills chickens and drinks their blood — straight from their dripping necks;

- The grandmother transforms into a chicken with a human head;

- The mother gives birth to a monstrous creature that looks like a Garbage Pail Kid; and

- The narrator goes mano-a-mano with a flotilla of zombie infants.

After nearly one hundred pages of blood-soaked insanity, we find ourselves right back where we started: the narrator begins his soliloquy about the house again, using the same words and wandering the same corridors as he did in the book’s opening pages.

Hino’s artwork resembles a scratchboard drawing or a woodblock print, characterized by large patches of black ink pierced by thin, white lines. In the opening pages, for example, there’s no visible light source anywhere in the house or the surrounding woods — no sky, no candles or lamps — creating an atmosphere of almost unbearable claustrophobia; the shadows are palpable, pressing in on the narrator just as surely as the demons he unwittingly frees later in the story.

Character-wise, Hino’s designs belong to the same genotype as Kazuo Umezu and Kanako Inuki’s. Hino draws young girls and mothers as beautiful, glassy-eyed dolls and old women, fathers, and boys as grotesques. The narrator, for example, wears his worry like a shirt; he has enormous eyes rimmed in circles and is almost bald, even though his behavior and height peg him as a child of about ten or twelve. The grandparents, by contrast, resemble animals: the grandfather looks like a toad, with a bumpy hide, wide-set eyes, and a broad, leering mouth filled with rotting teeth, while the grandmother increasingly resembles the object of her delusion:

For all Hino’s ability to provoke and amuse, I’m not sure how I feel about The Red Snake. The story unfolds with the feverish logic of a dream, yielding some suitably creepy and bizarre images; I’ve never pictured the Sanzu River as alive with flesh-eating zombie babies, but it’s an arresting idea. The ending, too, is surprisingly effective. It’s not clear if the narrator realizes that he’s trapped in a cycle of unending horror, or is simply puzzled that all of the house’s nameless inhabitants have reverted to their “normal” state; either way, it’s a nasty punchline that subverts our desire — and the narrator’s — for closure.

At the same time, however, Hino has a juvenile fixation with blood, pus, and bugs, relishing every opportunity to draw a close-up of the grandfather’s boil or fill the page with a squirm of insects. Though some of these images merit an appreciative eewww, they’re too broadly cartoonish to really spook us; the grandfather’s ailments reminded me of an old George Carlin routine about the perverse delight humans take in studying their hangnails and pimples, rather than the disturbing metamorphoses found in Junji Ito and David Croenberg’s work. Maybe that’s Hino’s point: that we’re weirdly — almost comically — obsessed with our own bodily existence, but The Red Snake is so packed with ideas and sight gags and detours into the ludicrous that it’s hard to know what, exactly, Hino is trying to do besides mess with our heads.

THE RED SNAKE • BY HIDESHI HINO • DH PUBLISHING • 200 pp. • NO RATING (APPROPRIATE FOR OLDER TEENS AND MATURE AUDIENCES; SEXUAL CONTENT AND DISTURBING IMAGERY)