I’ve always heard great things about Yellow Tanabe’s Kekkaishi (Viz) from eminently reliable sources, but I’ve dawdled on taking a serious look at the series because I feel so late to the party. When a title hits its twenties and you haven’t really tried it, there’s a barrier to entry. Viz, in its ongoing efforts to get more of my money, has softened that barrier by offering a 3-in1 edition of Kekkaishi.

I’ve always heard great things about Yellow Tanabe’s Kekkaishi (Viz) from eminently reliable sources, but I’ve dawdled on taking a serious look at the series because I feel so late to the party. When a title hits its twenties and you haven’t really tried it, there’s a barrier to entry. Viz, in its ongoing efforts to get more of my money, has softened that barrier by offering a 3-in1 edition of Kekkaishi.

You know that I’m very pro-omnibus. I’m not a fiend about paper quality; if I can focus on the page I’m reading instead of what’s on the flip side, I’m perfectly content. For me, it’s a worthwhile trade-off if it results in more content for a lower price. And sometimes the larger span of content makes a more persuasive case for the series that a single volume could. The first third of this collection is likeable but not particularly gripping. It takes a while for Tanabe to get into her groove and for the series to really take off.

Kekkaishi tells the story of young exorcists who spend their nights protecting their school from demons that range from pesky to violently destructive. The school used to be the site of a clan led by a lord whose spiritual aura made him something of a demon magnet. This forced him to hire a powerful exorcist to protect his home and family. After the exorcist’s death, his disciples split into two factions, each thinking their efforts were superior.

Yoshimori and Tokine are the chosen heirs of those two families of exorcists, and even though the family they served is long gone, their land is still demon central. It’s also the place where the kids spend their day in class. Tokine is a couple of years older than Yoshimori. She’s diligent in her training, and she’s eager to accept the family mantle. Yoshimori is resentful over the fact that he’s been forced onto the family career track, but his attitude changes when Tokine is hurt because of his carelessness and lack of skill. He vows to become a better kekkaishi, not to fulfill the family legacy, but to make sure his friend Tokine isn’t hurt again. (The emotional arc of his origin story is a much less dour version of Peter Parker’s, basically.)

That’s a lot of explanation, but it’s necessary, and Tanabe presents it in a lively manner. It sets up the relationship between Yoshimori and Tokine, which is as central to the series as the demon battles. Of course, the demon battles aren’t to be sneezed at. The kekkaishi’s skill set is refreshingly straightforward: they trap the demons in cubic force fields, then banish them. Things get complicated depending on the strength and malice of the demon in question, and Tanabe draws these sequences with great skill and clarity. Designs for the demons are wonderfully varied.

That’s a lot of explanation, but it’s necessary, and Tanabe presents it in a lively manner. It sets up the relationship between Yoshimori and Tokine, which is as central to the series as the demon battles. Of course, the demon battles aren’t to be sneezed at. The kekkaishi’s skill set is refreshingly straightforward: they trap the demons in cubic force fields, then banish them. Things get complicated depending on the strength and malice of the demon in question, and Tanabe draws these sequences with great skill and clarity. Designs for the demons are wonderfully varied.

In the first volume, it can seem like Tanabe is holding back, sticking to short but effective stories rather than really digging into her characters and situations. Maybe the feat of collecting a full volume of material gave her the confidence to go deeper, since the second volume opens with a very involving multi-story arc that examines Tokine’s past and introduces more detail about the larger supernatural culture of the kekkaishi and the mystical types around them. From there, Tanabe goes from strength to strength, alternating between exciting battles, arcs full of emotional undercurrents, and goofy one-off stories that bridge between larger tales.

Aside from general approval of the series overall, there are some elements that I really, really like. One of them is the fact that she can render Yoshimori’s training in ways that are interesting and entertaining, which is a rare feat for a shônen mangaka. The kekkaishi’s means of battle are so simple, but Tanabe has given a lot of thought to how they can be applied, and it’s fun to watch the characters figure out the variations.

Another highlight are the cranky old people. Yoshimori’s crotchety grandfather and Tokine’s sly, spry granny are constantly trying to get each other’s goat. It’s the kind of half-serious, half-reflexive squabbling that can really liven up the vibe. Best of all is that they both get moments that reveal them as formidable kekkaishi in their own right.

Another highlight are the cranky old people. Yoshimori’s crotchety grandfather and Tokine’s sly, spry granny are constantly trying to get each other’s goat. It’s the kind of half-serious, half-reflexive squabbling that can really liven up the vibe. Best of all is that they both get moments that reveal them as formidable kekkaishi in their own right.

The third element that I particularly enjoy is Tokine. In her author notes, Tanabe explains the character’s conception. She didn’t want to create a victim for the hero to rescue over and over, and she wanted to give Tokine some advantages that made her Yoshimori’s equal. Tanabe succeeded admirably in that regard. Tokine isn’t as powerful as Yoshimori, but she’s more skilled and certainly more mature. She’s an almost serene, steely presence amidst the demon-fighting mayhem, though she has her own goofy foibles. You can see why Yoshimori has such a huge crush on her, even if she doesn’t acknowledge it.

I didn’t really need another long, ongoing series on my to-read list, but I’m glad to add Kekkaishi to it. It’s got all of the elements of a sturdy supernatural adventure with plenty of quirks to keep things from turning formulaic. While I doubt Viz will run through the series entire back catalog in the 3-in1 format, it’s not so oppressively long that it will cost a fortune to fill in the gaps. And the series is available on the publisher’s iPad app, making that process relatively simple. I hope this strategy gives Kekkaishi the commercial boost it deserves.

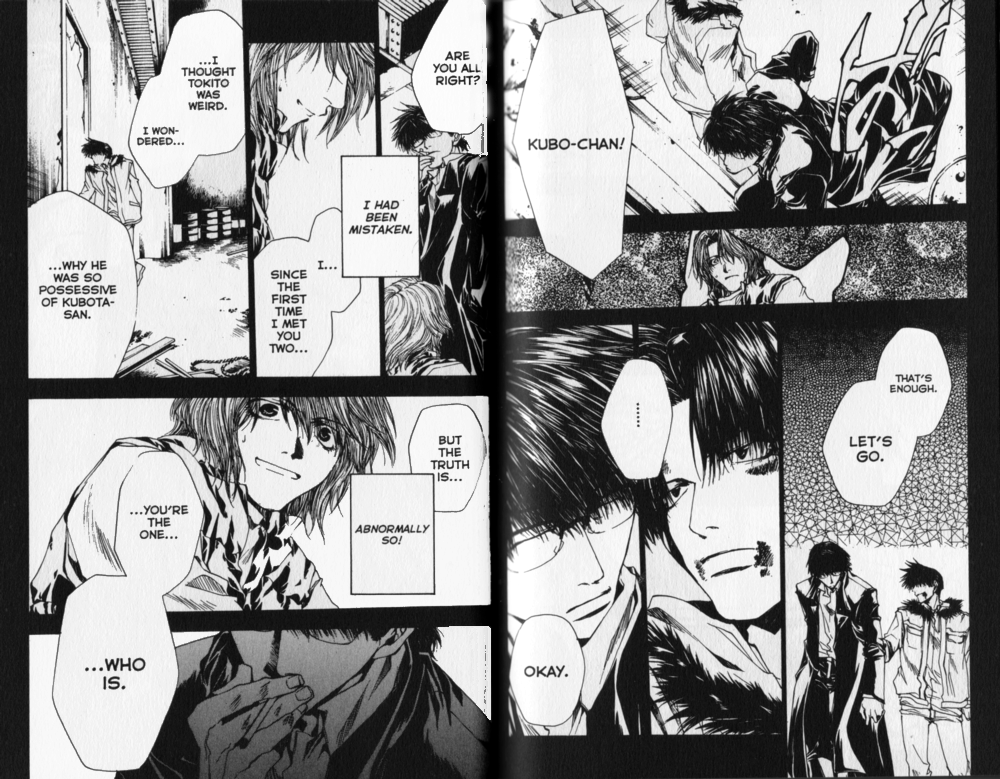

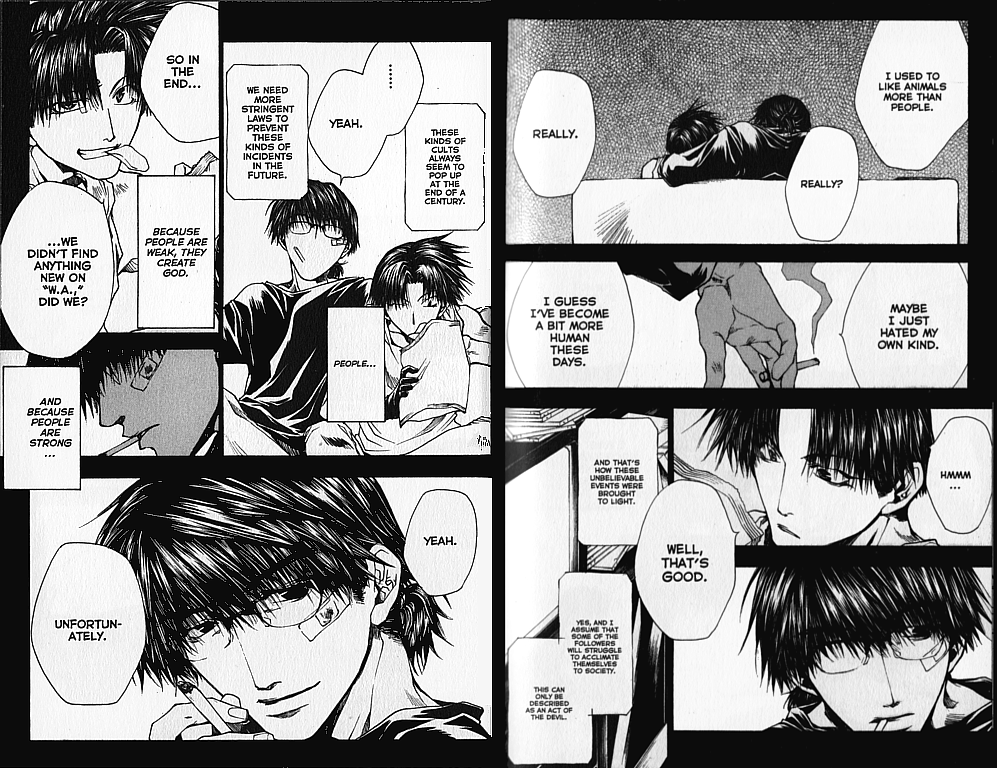

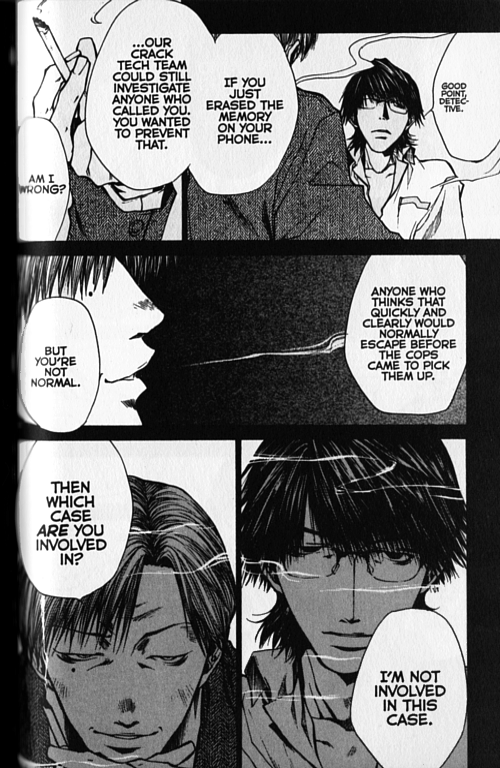

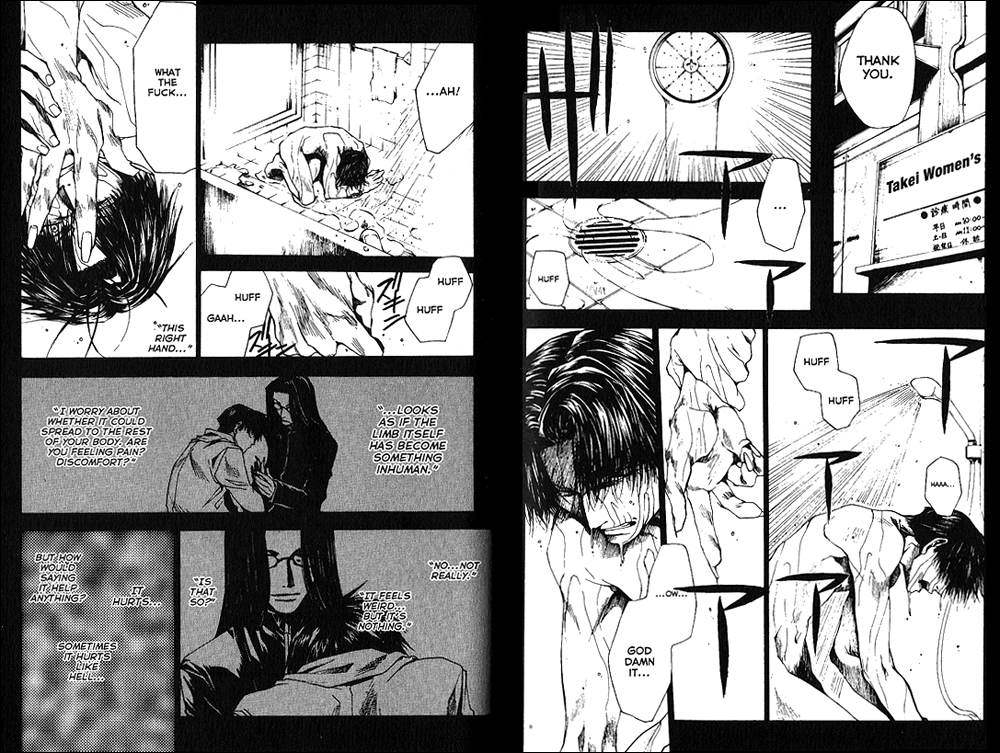

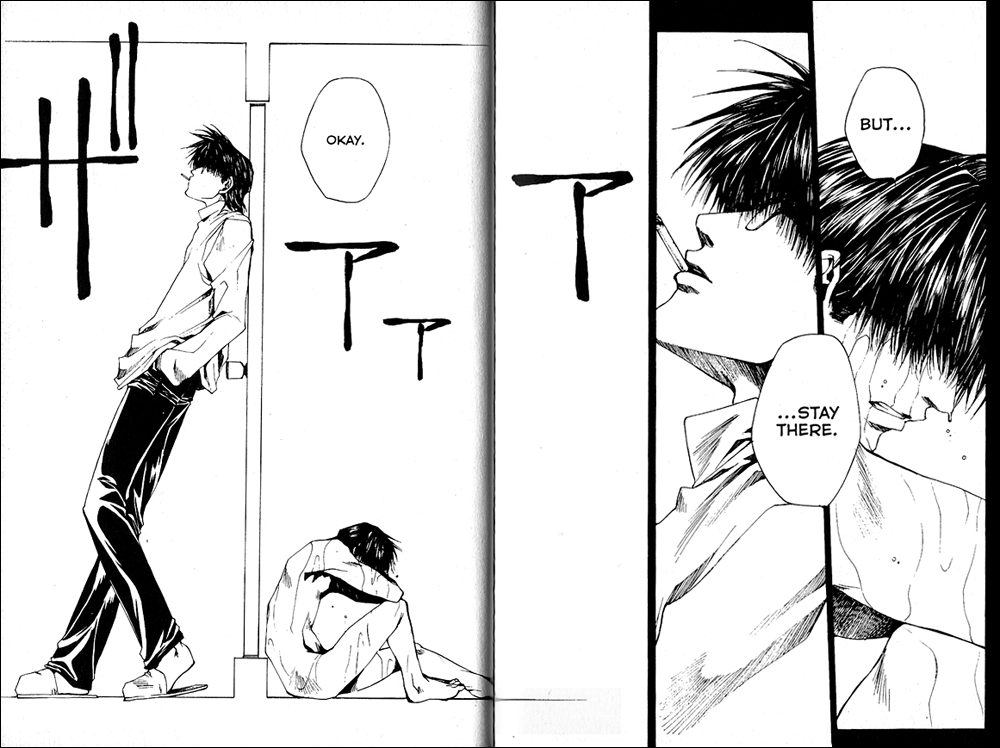

One of my favorite quotes so far from this month’s Manga Moveable Feast comes from David Welsh, as he describes why Wild Adapter is, in his words, “

One of my favorite quotes so far from this month’s Manga Moveable Feast comes from David Welsh, as he describes why Wild Adapter is, in his words, “