With almost every installment of the Manga Moveable Feast, we tend to ask the question, “Why this particular title?” In the case of Natsuki Takaya’s Fruits Basket, published in English over the course of 23 volumes by Tokyopop, I think the answer is complex.

With almost every installment of the Manga Moveable Feast, we tend to ask the question, “Why this particular title?” In the case of Natsuki Takaya’s Fruits Basket, published in English over the course of 23 volumes by Tokyopop, I think the answer is complex.

First of all, it’s almost always interesting to dig into a cultural phenomenon. In the period between the initial English-language publication of Sailor Moon by Tokyopop and its upcoming republication by Kodansha, Fruits Basket was the most commercially successful shôjo manga and one of the most commercially successful manga, period.

Many people have made the argument that romantic fantasy for a female audience tends to be critically undervalued. Commercially successful romantic fantasy for a female audience adds another potential disclaimer for a book’s artistic value. Fruits Basket wasn’t just primarily for girls, but girls liked it a lot. And they bought as many copies of it as boys did of manga they liked. What’s that about? Or, at least that sometimes seems like the psychological subtext.

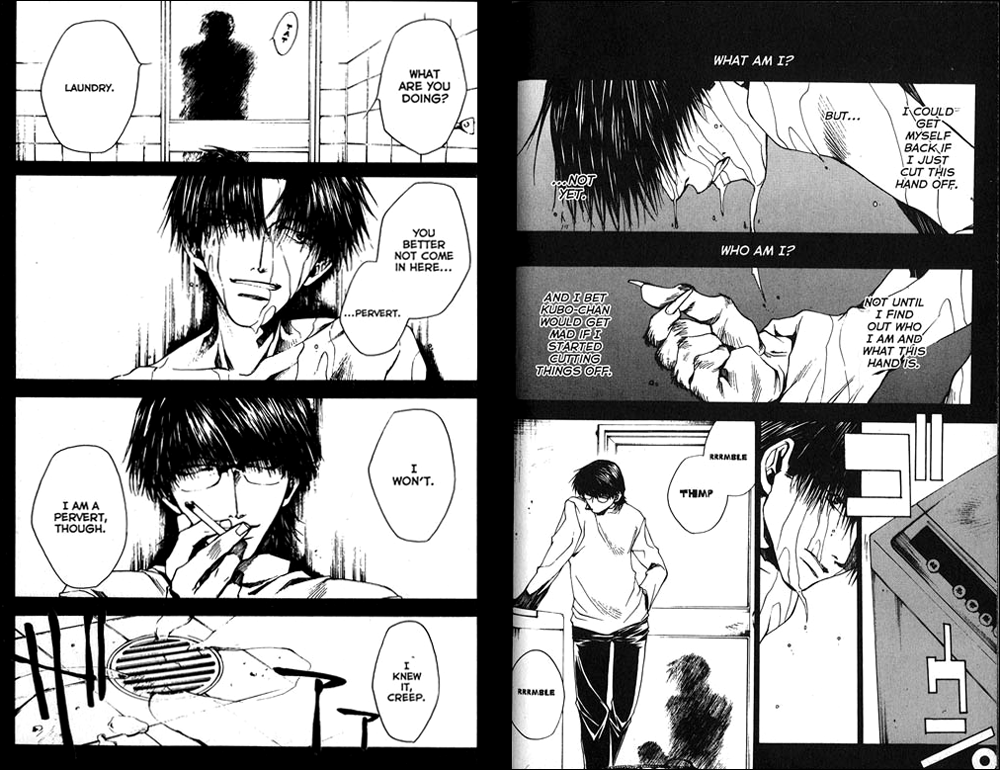

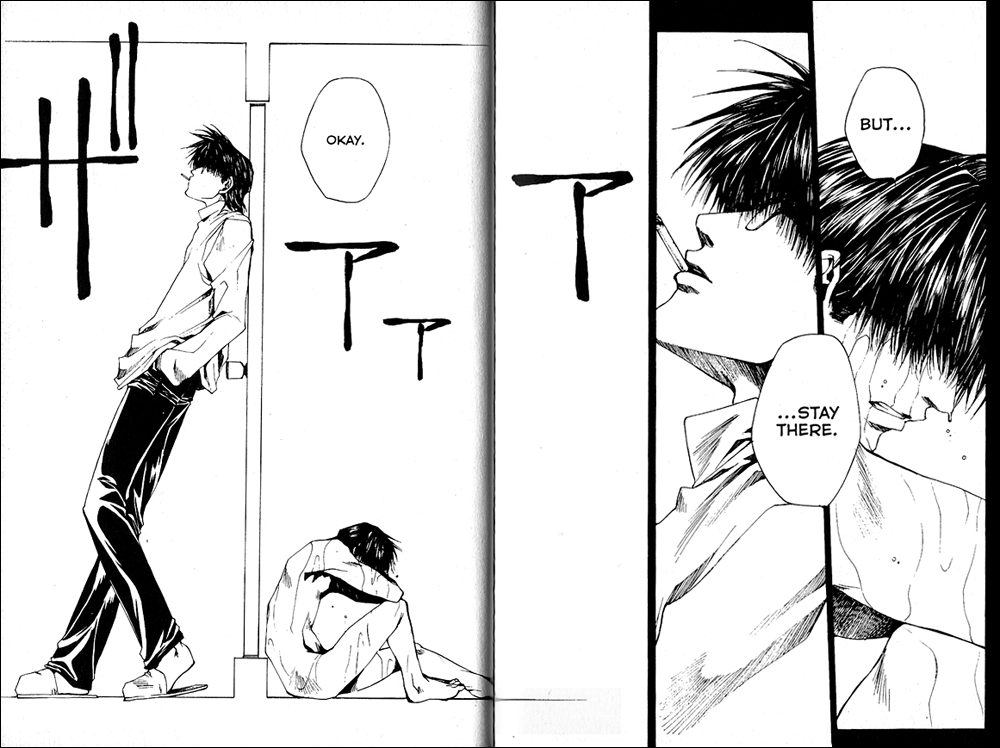

And Fruits Basket, which originally ran in Hakusensha’s Hana to Yume, is difficult to quantify. It’s shares a number of qualities with more generic manga of its category – an optimistic but kind of dingbat heroine, two hunky boys engaged in a rivalry for her attentions, a seemingly cutesy curse, and so on. But Takaya approaches that material with quite a bit of craft and emotional ruthlessness. She doesn’t brutalize her characters (or her readers), but she doesn’t spare them much. It’s not a creepy, “suffering and terror are hot” kind of approach; it’s more of a fluid, applied grasp of the nature of tragedy. Fruits Basket has scale. If the aesthetic were less contemporary-casual, the Takarazuka Revue could operetta up this sprawling epic.

It takes a while for things to fall into place, to be honest. Initially, the series seems like what its cover blurb describes: a story about a plucky orphan who moves in with a family of hot guys who are living under a curse! They turn into animals represented in the Chinese Zodiac when they’re hugged by someone of the opposite sex! Eventually, though, the cutesy sheen of the curse gives way to the profound dysfunction and deep, deep pain of the Sohma family. And the ditsy charm of Tohru Honda, the outsider in the tearstained zoo, resolves into resolve and force and generosity of spirit.

I hope you’ll give a few volumes a try. My plan for the week is to focus on some of my favorite moments from the series and to keep a running tally of each day’s posts, if posts there are. I’m looking forward to the contributions of anyone who cares to do so.

Previous Manga Moveable Feasts:

- Sexy Voice and Robo

- Emma

- Mushishi

- To Terra

- Color of… Trilogy

- Paradise Kiss

- Yotsuba&!

- Afterschool Nightmare

- One Piece

- Karakuri Odette

- Barefoot Gen

- Aqua and Aria

- Rumiko Takahashi

- Cross Game

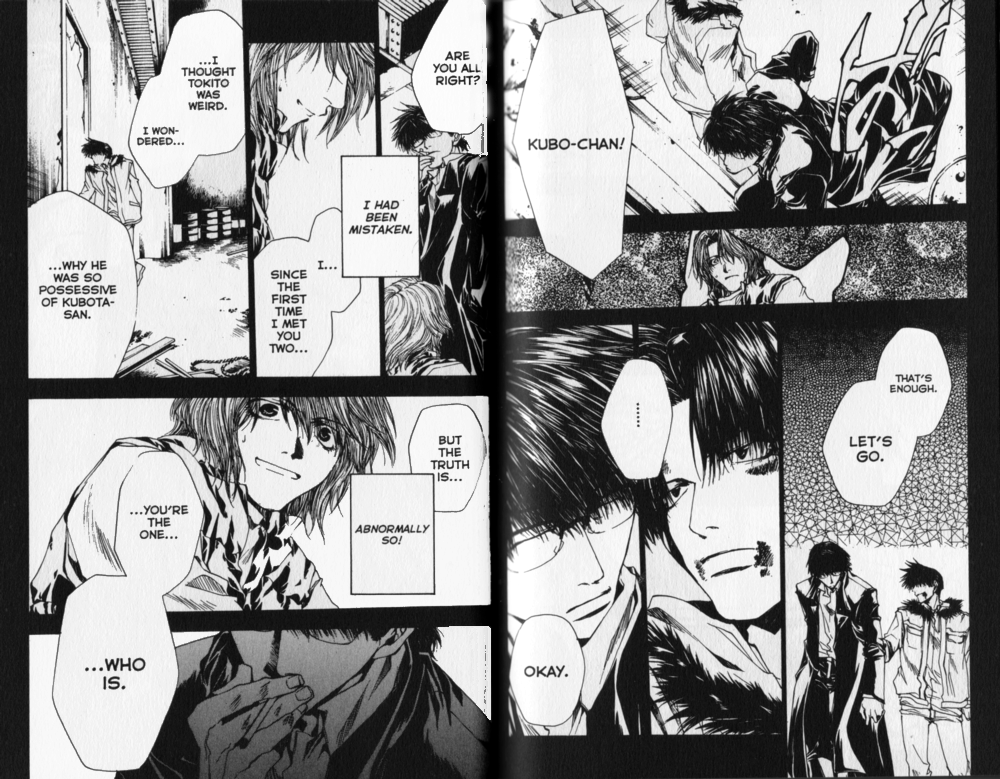

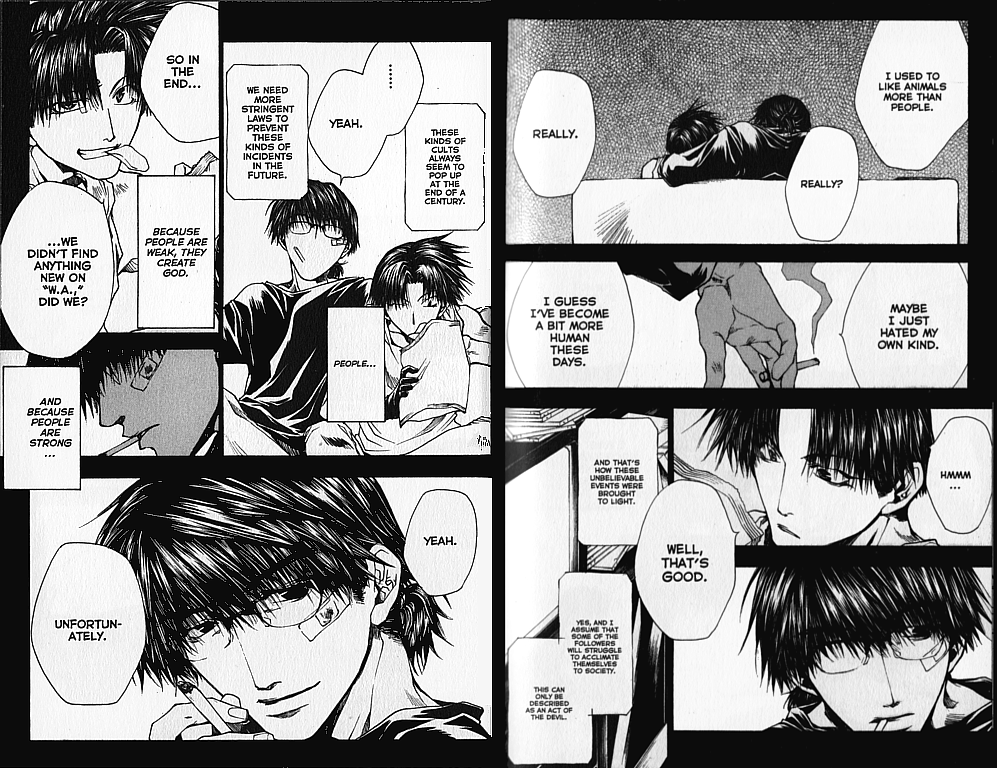

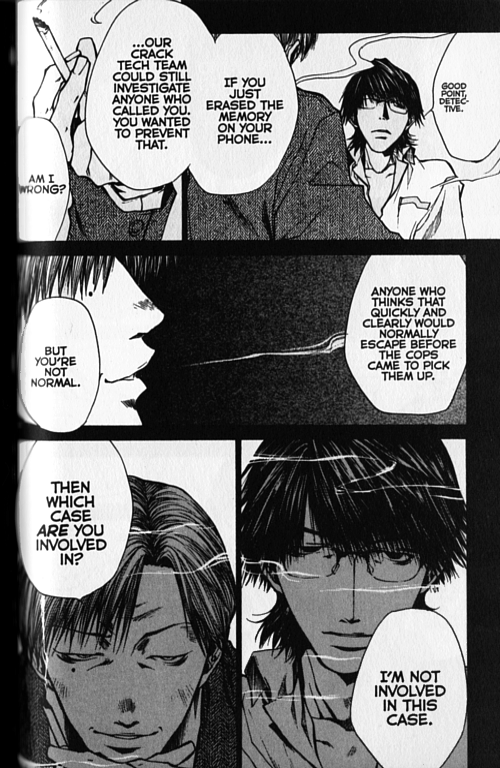

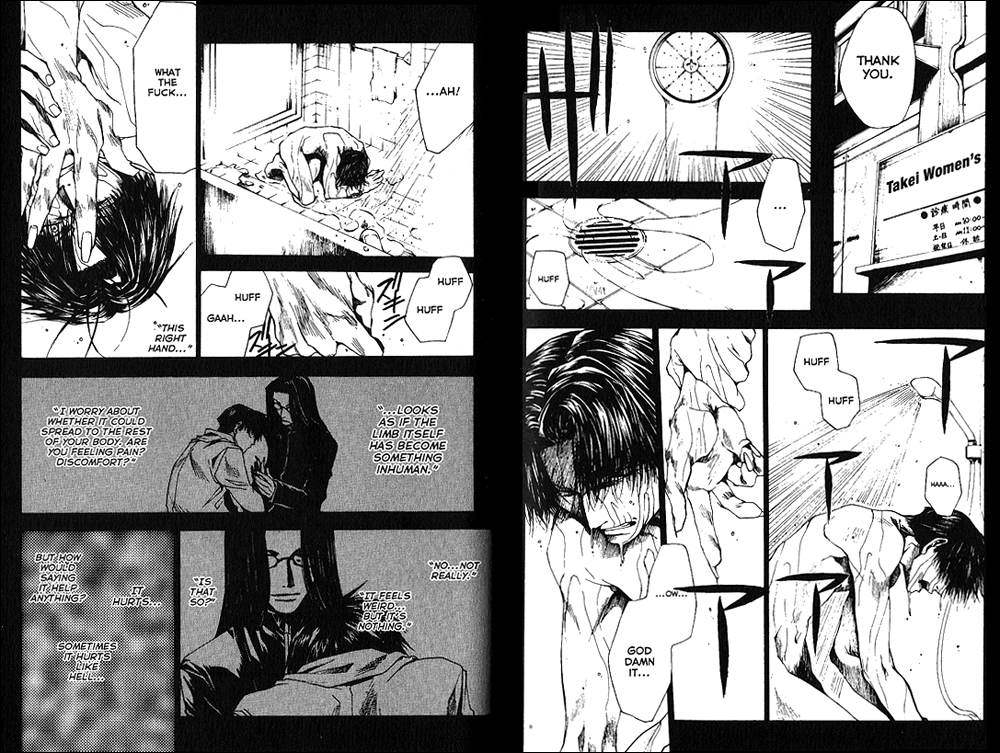

- Wild Adapter