And the winner of the Triton of the Sea manga giveaway is…Haley S.!

And the winner of the Triton of the Sea manga giveaway is…Haley S.!

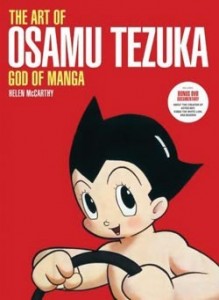

As the winner, Haley will be receiving a copy of the first omnibus in Osamu Tezuka’s series Triton of the Sea. About a year ago, I came to the realization that I had read quite a few manga that featured merfolk of one sort or another. And so for this giveaway, I was interested in learning about all of the mermaids and mermen that other people had come across while reading manga. I’ve complied a list below of manga that feature merfolk, but be sure to check out the giveaway comments for more details on some of them.

Some of the manga in English featuring merfolk:

Castle of Dreams by Masami Tsuda

Children of the Sea by Daisuke Igarashi

A Centaur’s Life by Kei Murayama

Berserk by Kentaro Miura

The Earl and the Fairy by Ayuko

Legendz written by Rin Hirai, illustrated Makoto Haruno

Mermaid Saga by Rumiko Takahashi

Monster Musume: Everyday Life with Monster Girls by Okayado

Moon Child by Reiko Shimizu

One Piece by Eiichiro Oda

Pichi Pichi Pitch written by Michiko Yokote, illustrated by Pink Hanamori

Princess Mermaid by Junko Mizuno

Selfish Mr. Mermaid by Nabako Kamo

Triton of the Sea by Osamu Tezuka

Tropic of the Sea by Satoshi Kon

I was a little lenient with the definition of merfolk above (mostly because I wanted an excuse to include Daisuke Igarashi’s Children of the Sea) and I’m certain that it’s not a comprehensive list, either. But, it should be a good place to start if you’re looking for some mermen or mermaids in manga. Thank you to everyone who participated in this month’s giveaway; I hope to see you all again for the next one, too!

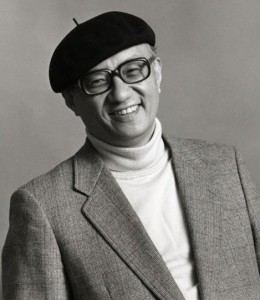

MICHELLE: As we occasionally do when the Manga Moveable Feast rolls around, MJand I have opted to dedicate this week’s Off the Shelf column to the topic at hand, which this month is the works of Osamu Tezuka. Specifically for our case, we’re going to be talking about Princess Knight, Tezuka’s shoujo manga about Sapphire, a princess who accidentally receives both a boy’s heart and a girl’s heart at the time of her birth, and who, when we pick up her story as an adolescent, has somewhat of an identity crisis while undergoing many wacky hardships/hijinks.

MICHELLE: As we occasionally do when the Manga Moveable Feast rolls around, MJand I have opted to dedicate this week’s Off the Shelf column to the topic at hand, which this month is the works of Osamu Tezuka. Specifically for our case, we’re going to be talking about Princess Knight, Tezuka’s shoujo manga about Sapphire, a princess who accidentally receives both a boy’s heart and a girl’s heart at the time of her birth, and who, when we pick up her story as an adolescent, has somewhat of an identity crisis while undergoing many wacky hardships/hijinks. MJ: That may be a generous assumption, but I’ll give it to him if you will. You know, I think what’s most disappointing to me about Princess Knight is that I feel like I really could have liked it. Tezuka’s artwork is so much fun here, and so full of life. And I’m really fine with the “Looney Tunes approach,” as you so brilliantly put it. I think this manga could have been a lot of fun. But the gender issues are so profound, they kinda take over the whole thing for me.

MJ: That may be a generous assumption, but I’ll give it to him if you will. You know, I think what’s most disappointing to me about Princess Knight is that I feel like I really could have liked it. Tezuka’s artwork is so much fun here, and so full of life. And I’m really fine with the “Looney Tunes approach,” as you so brilliantly put it. I think this manga could have been a lot of fun. But the gender issues are so profound, they kinda take over the whole thing for me.