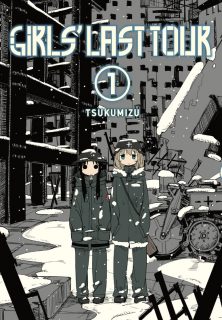

Was Tsukumizu an architect in a previous life? That question lingered with me as I read volume one of Girls’ Last Tour, a sci-fi manga that unfolds in a not-too-distant future filled with crumbling infrastructure and empty cities. Tsukumizu details the physical environment with precision, from sagging girders and abandoned cranes to pockmarked skyscrapers, broken trestles, and rusting water tanks. The sense of loss is palpable on every page, whether the principal characters are surveying an airplane “graveyard” filled with rusting turboprops, or searching for safe passage through a partially flooded city. Though we don’t learn what caused the devastation, Tsukumizu’s vivid illustrations suggest that the world we’re seeing was torn apart by violence.

If only the characters were rendered with such specificity! Yuuri and Chito — the “girls” of the title — are opposites: Yuuri is the brawn, Chito the brain. Both are so focused on their own survival that we have little sense of who they were before the apocalypse, or what brought them together. That in itself isn’t a fatal flaw; Robert Redford’s character in All Is Lost, for example, had no obvious backstory to explain why he was sailing by himself, or who might miss him if he drowned at sea. Yet the movie was compelling, as Redford’s character was painfully aware of his own vulnerability, and the unlikeliness of being rescued. In Girls’ Last Tour, by contrast, the dramatic stakes are low; many chapters revolve around simple activities — jerry building a hot tub, finding a place to sleep — that don’t reveal much about either girl’s personality, or the dangers they face.

The one exception is a story arc spanning chapters six, seven, and eight, in which Yuuri and Chito meet a cartographer who’s been diligently mapping an unnamed city. When an accident scatters Kanazawa’s maps to the wind, his anguish at their loss generates a visceral jolt of emotion. “I may as well fall with them,” he declares, a statement that Chito and Yuuri forcefully reject before dragging Kanazawa to safety atop a tower. As they peer out over the city, their bodies dwarfed by sky and buildings, the darkness gives way to a brilliant patchwork of lights that illuminate their faces and the rooftops around them — a potent reminder that the city once teemed with life.

Tsukumizu frustrates the reader’s efforts to make sense of the characters, however, by drawing Chito and Yuuri as a pair of affectless automatons. Yuuri’s comments about the lights indicate that she’s genuinely moved, but her face and her body don’t register any emotion; she might as well be discussing what she had for dinner, or whether railroad ties make good firewood. Perhaps the flatness of her delivery is meant to convey just how weary she is, or how pragmatic she must be to survive, but the banality of her conversations with Chito suggest that Tsukumizu had some difficulty creating characters as sharp and memorable as the world they inhabit.

The bottom line: Your mileage will vary: some people may appreciate the series’ absence of dramatic conflict, while others may find it a little too measured to be engrossing. I’m on the fence about this one; on the strength of the final story arc, however, I’ll be picking up volume two.

GIRLS’ LAST TOUR, VOL. 1 • STORY AND ART BY TSUKUMIZU • TRANSLATION BY AMANDA HALEY • YEN PRESS • RATED T, FOR TEEN (13+) • 162 pp.