Welcome to the May Manga Movable Feast! On the menu: Keiko Takemiya’s award-winning sci-fi epic To Terra. If you’ve never dined with us before, here’s how the MMF works: every month, the manga blogging community holds a week-long virtual book club in which we discuss a particular series or one-shot. Each day, the host shares links to new blog entries focusing on that work, while building an archive for the entire week’s discussion. At the end of the week, the group then selects a new host and a new “menu” for the following month.

Our “feast” has two goals. The first is to promote intelligent, in-depth analysis of manga we love (or, in some cases, hate). Previous contributions have run the gamut from straightforward reviews to an interview with Sexy Voice and Robo editor Eric Searleman, a guided tour through Kaoru Mori’s “Emmaverse,” and an essay contrasting Urushibara’s Mushishi with Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos. The second goal is to foster a sense of community among avid manga readers. Everyone is invited to take part in the MMF, regardless of whether you’ve participated before. If you have your own blog, simply send me the link to your To Terra-themed post, whether it’s a brand new essay written expressly for the MMF or an older review that you’d like the share with the community, and I’ll include it in my daily round-up. If you don’t have a blog, send me your text and I’ll post your ideas here. (Click here for my email.) Discussion begins today and will run through the week until Sunday, May 30th.

Below, I’ve provided an overview of the series’ publication history, plot, and place in the manga canon. You can follow the discussion by checking the daily blog posts, clicking on the Manga Movable Feast tag, or visiting the MMF archive: http://mangacritic.com/?page_id=4766.

TO TERRA: THE PUBLICATION HISTORY

To Terra debuted in 1977 in Gekkan Manga Shonen. During its three-year run, To Terra nabbed two honors: the Shogakukan Manga Award and the Seiun Award, an annual prize for the best new science fiction published in Japan. (To Terra was the first manga to receive a Seiun Award; later winners would include Appleseed, Domu: A Child’s Dream, Urusei Yatsura, Cardcaptor Sakura, Planetes, and 20th Century Boys.) The series was originally issued in tankubon format in 1980 by Asahi Sonorama, and reissued again in 2007 by Square Enix, around the same time Vertical, Inc. released the first English-language edition.

To Terra has enjoyed considerable popularity in Japan, thanks, in part, to several adaptations: a 1979 NHK radio drama; a 1980 movie, produced by Toei Animation; and a 2007 animated television series, produced by Aniplex.

TO TERRA: THE STORY

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society.

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society.

The real purpose of these checks is to weed out an unwanted by-product of S.D.-era genetic engineering: the Mu, a race of telepathic mutants. After decades of persecution, the Mu fled Terra, seeking refuge beneath the surface of Ataraxia. Under the leadership of Soldier Blue, they escaped detection by humans. But Soldier Blue is frail and dying (though he has chosen to project a youthful, sparkly-eyed appearance), and seeks a successor in Jomy Marcus Shin, a 14-year-old who possesses both the telepathic ability of a Mu and the hardier constitution of a human. As the series unfolds, we watch Jomy develop into a formidable leader, capable of inspiring passion, loyalty, and sacrifice among the Mu as they struggle to return to their homeworld. Running in counterpoint to Jomy’s story is that of Keith Anyan, an elite solider-in-training and future Terran leader. Keith enjoys a privileged position in human society. Yet he is plagued by doubt: why doesn’t he remember his childhood? Or his foster parents? And why does Mother refuse to eradicate the Mu when the state has deemed them a threat to mankind?

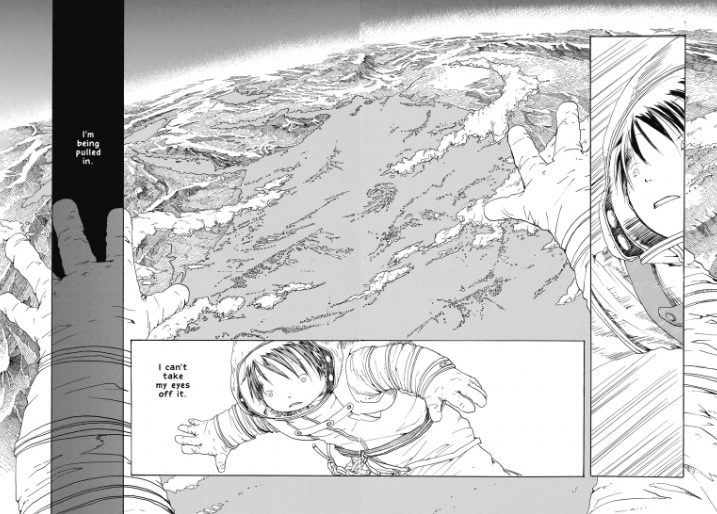

What makes this unabashedly Romantic mash-up of Star Trek, Star Wars, and 2001 both entertaining and moving is the richness of Keiko Takemiya’s universe. On the surface, To Terra is a beautifully illustrated soap opera, the kind of manga in which the heroes have terrific hair, wear smart jumpsuits, and keep psychic squirrels as pets. But To Terra can also be read a cautionary tale about mankind’s poor custodianship of the Earth; a scathing critique of eugenics and social engineering; a meditation on the relationship between memory and identity; and, most significantly, a critique of adult hypocrisy. It’s this multivalent quality that elevates To Terra from a mere allegory to an epic space opera as engaging, beautiful, and thought-provoking as Tezuka’s best work. (This review originally appeared at PopCultureShock on July 16, 2007.)

TO TERRA: ITS PLACE IN THE CANON

As anyone with a passing familiarity with the Magnificent 49ers knows, the 1970s were a watershed in the development of shojo manga. Not that shojo manga was an invention of the 1970s, of course; shojo manga traces its roots back to the 1910s, when girls’ magazines began running short, one-page gag strips, and underwent several major stages of development before evolving into the medium we know today. Until the mid-1960s, however, shojo manga was written by men for pre-teen girls; the stories were sweet, sentimental, and chaste, often revolving around family, class, and identity in the manner of a Frances Hodgson Burnett story. In an interview with manga scholar Matt Thorn, Keiko Takemiya’s former roommate Moto Hagio remembers the manga from this period:

In the girls’ comics, you would have stories in which the woman you thought was the mother turns not to be the mother, and the real mother is actually somewhere else. There was a variety of settings. For example, the poor child in the story turns out to actually come from a rich family, or the child of a rich family turns to have been adopted from a poor family. And one of the standard device was amnesia… It appeared so often, it makes me think that what with the war and the harsh social conditions, people had an unconscious desire to forget everything. So the heroine goes off in search of her real mother, but along the way she develops amnesia, and ends up being taken care of by a string of kind strangers.

Another popular motif was ballet. There was quite a boom in girls’ comics about ballet for a while. For example, the heroine would be a girl from a poor family who’s really good at ballet, but she loses the lead to an untalented girl from a rich family. In the standard story, there would be a mean girl and a kind-hearted heroine, and there would be a very clear-cut struggle between good and evil.

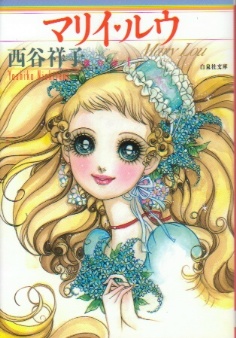

In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in “The Multi-Faceted World of Shoujo Manga,” the heroines of early shojo stories were too young for crushes and dates, so romance was the provenance of older, secondary characters.) Though tame by contemporary standards, Mary Lou’s emphasis on the heroine’s emotional life and relationships proved highly influential, paving the way for other artists to write stories that focused on the everyday concerns of teenagers, rather than the melodramatic travails of poor little rich girls.

In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in “The Multi-Faceted World of Shoujo Manga,” the heroines of early shojo stories were too young for crushes and dates, so romance was the provenance of older, secondary characters.) Though tame by contemporary standards, Mary Lou’s emphasis on the heroine’s emotional life and relationships proved highly influential, paving the way for other artists to write stories that focused on the everyday concerns of teenagers, rather than the melodramatic travails of poor little rich girls.

Nishitani was a pioneer in another sense as well: she inspired dozens of women to enter what had been an overwhelmingly male profession. Those artists who followed Nishitani into the field in the 1970s — women like Takemiya, Hagio, and Ryoko “Rose of Versailles” Ikeda — built on her legacy, helping complete the transformation of shojo manga from staid stories about good girls to a multi-faceted storytelling medium capable of dramatizing the characters’ inner thoughts as forcefully as their physical actions. The 49ers embraced genres such as science fiction and fantasy, and developed new ones as well: the entire boys’ love industry owes a debt to Hagio and Takemiya for ground-breaking stories such as “The Heart of Thomas” and The Song of the Wind in the Trees. Whatever the subject matter, however, the 49ers used the comics medium to explore fundamental questions about identity — what constitutes family? what does it mean to be female? what distinguishes the child from the adult? — and love in all its manifestations, from maternal to carnal.

To Terra, which addresses many of the themes found in Takemiya’s other works, is significant precisely because it isn’t shojo; Takemiya was one of the first female artists to write for a boys’ magazine, bringing a distinctly shojo sensibility to her portrayal of Keith and Jomy’s emotional lives. The popular success of To Terra created opportunities for other manga-ka to cross over as well, a trend important enough for Frederick Schodt to make note of it in Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics (1983). Contemporary artists such Rumiko Takahashi, CLAMP, Yellow Tanabe, and Hiromu Arakawa owe a debt to Takemiya, as she helped demonstrate what seems patently obvious to us now: that women are just as capable of writing for male audiences as men are. Oh, and we can draw a pretty bitchin’ space ship if the story calls for one.

FOR FURTHER READING

Aoki, Deb. “Interview: Keiko Takemiya, Creator of To Terra and Andromeda Stories.” About.com: Manga. January 22, 2008. (Accessed 5/23/10.)

Thorn, Matt. “The Moto Hagio Interview.” The Comics Journal 269 (July/August 2005). (Accessed 5/23/10.)

Thorn, Matt. “The Multi-Facted Universe of Shoujo Manga.” Conference paper. 2008. (Accessed 5/23/10.)

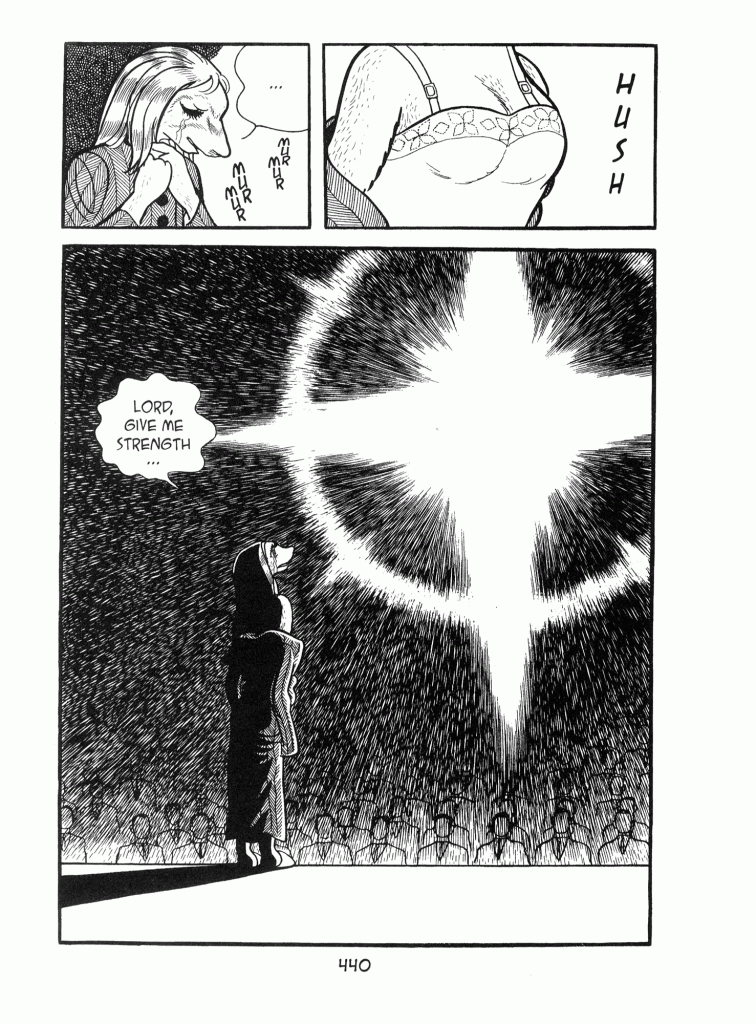

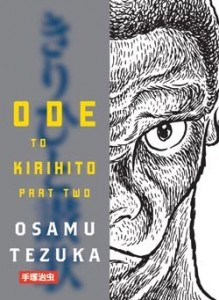

At a deeper level, however, Ode to Kirihito is an extended meditation on what distinguishes man from animal. Kirihito’s physical transformation forces him to the very margins of society; he terrifies and fascinates the people he encounters, as they alternately shun him and exploit him for his dog-like appearance. (In one of the manga’s most engrossing subplots, an eccentric millionaire kidnaps Kirihito for display in a private freak show.) The discrimination that Kirihito faces — coupled with Monmow’s dramatic symptoms, such as irrational aggression and raw meat cravings — lead him to question whether he is, in fact, still human. Throughout the story, he wrestles with a strong desire to abandon reason and morality for instinct; only his medical training — and the ethics thus inculcated — prevent him from embracing the beast within.

At a deeper level, however, Ode to Kirihito is an extended meditation on what distinguishes man from animal. Kirihito’s physical transformation forces him to the very margins of society; he terrifies and fascinates the people he encounters, as they alternately shun him and exploit him for his dog-like appearance. (In one of the manga’s most engrossing subplots, an eccentric millionaire kidnaps Kirihito for display in a private freak show.) The discrimination that Kirihito faces — coupled with Monmow’s dramatic symptoms, such as irrational aggression and raw meat cravings — lead him to question whether he is, in fact, still human. Throughout the story, he wrestles with a strong desire to abandon reason and morality for instinct; only his medical training — and the ethics thus inculcated — prevent him from embracing the beast within.