Everything you need to know about LIVES is summed up by the following category tags: “big breasts,” “meteor,” “stranded,” “strategically torn clothing,” and “survival.” (Kudos to the Baka-Updates moderator who felt the need to give “strategically torn clothing” its due as a category. But what, no “hungry predators”?)

Plot-wise, LIVES resembles Battle Royale, Gantz, and King of Thorn in using a catastrophic event — in this case, a meteor shower — to deposit normal people into a hostile environment — here, a dense jungle inhabited by carnivorous monsters. It doesn’t take long for the refugees to discover the particularly nasty secret behind these beasties: they were originally human beings as well, and some can still transform back into their bipedal selves, with no memory of terrorizing their fellow survivors.

Art-wise, Taguchi delivers the goods, with scene after scene of expertly staged carnage. His monsters are perhaps a little too neat, lightbox chimaeras that originated in the pages of National Geographic, but they’re agile and vicious enough to be convincing. His humans also offer balm for tired eyes: the hero, Shingo, has abs that would shame The Situation’s, and the harem of doe-eyed, big-bosomed ladies wear just enough clothing to prevent the story from shading into pornography. (In a hilarious touch, all of the women’s shoes are in immaculate condition, even though their tops and skirts have been reduced to scraps. Paging Imelda Marcos!)

What’s missing is subtext. LIVES is the umpteenth manga to suggest when man lives in a “state of nature” — no rulers, no rules of law — that a “war of all against all” prevails, creating an environment where lives are “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” While other manga-ka have attempted to explore what happens to the human psyche when all social constraints disappear, Masayuki Taguchi focuses exclusively on those consequences that Thomas Hobbes forget to mention in The Leviathan: costume failures, near-rapes, faintly incestuous relationships, and hyper-violent showdowns between monsters and would-be meals. There’s nothing wrong with carnage and cheesecake; I’m all for brainless fun. But when the narrative falls into an all-too-predictable pattern of grope-chase-chomp-regroup in the very first volume, a little subtext goes a lot farther than a cool monster or a torn shirt in making things interesting.

Review copy provided by Tokyopop. Volume one will be released on February 1, 2011.

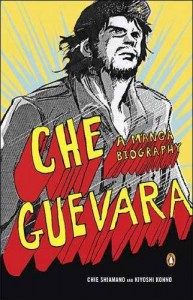

5. Che Guevara: A Manga Biography

5. Che Guevara: A Manga Biography