As depicted in most shojo and shonen manga, the Japanese high school is the epitome of order, with students in neat, military-style uniforms diligently studying for exams, tidying up classrooms, staging plays, and participating in cultural festivals. Students who don’t fit into the school’s established pecking order — social, athletic, or academic — quickly find themselves ostracized by their peers for lack of purpose.

As depicted in most shojo and shonen manga, the Japanese high school is the epitome of order, with students in neat, military-style uniforms diligently studying for exams, tidying up classrooms, staging plays, and participating in cultural festivals. Students who don’t fit into the school’s established pecking order — social, athletic, or academic — quickly find themselves ostracized by their peers for lack of purpose.

Taiyo Matsumoto, however, offers a very different image of the Japanese high school in his anthology Blue Spring. His subjects are the kids with “front teeth rotten from huffing thinner,” who “answer to reason with their fists and never question their excessive passions” — in short, the delinquents. Kitano High School, the milieu these kids inhabit, is a crumbling eyesore with graffiti-covered walls, trash-filled stairwells, and indifferent faculty. Students cut class and fill their after-school hours with girlie magazines, petty crime, and smack-talk at the local diner, marking time until they join the world of adult responsibility.

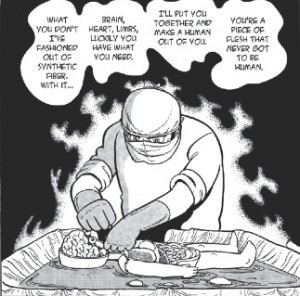

Gangs, bullies, disaffected teens playing at thug life — it’s familiar territory, yet in Matsumoto’s hands, these potentially cliche stories acquire a new and strange quality. Matsumoto eschews linear narrative in favor of digressions and fragments; as a result, we feel more like we’re living in the characters’ heads than reading a tidy account of their actions. Snatches of daydreams sometimes interrupt the narrative, as do jump cuts and surreal imagery: sharks and puffer fish drift past a classroom window where two teens make out, a UFO languishes above the school campus. Even the graffiti plays an integral part of Matsumoto’s storytelling; the walls are a paean to masturbation, booze, and suicide, cheerfully urging “No more political pacts–sex acts!”

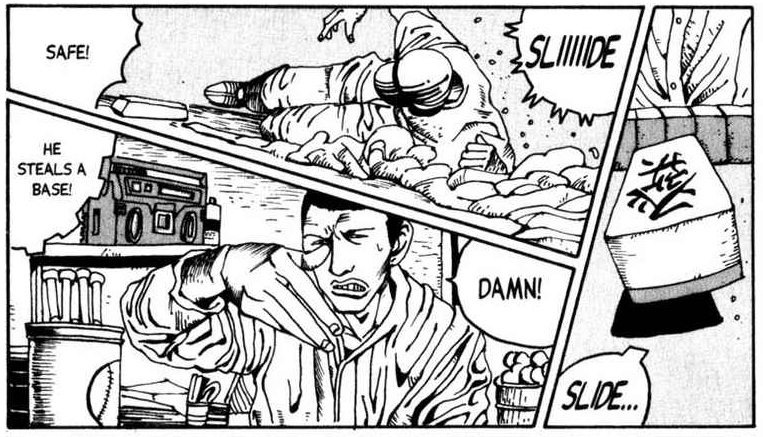

One of the most arresting aspects of Blue Spring is Matsumoto’s ability to manipulate time. In one of the book’s most visually stunning sequences, for example, Matsumoto seamlessly blends two events — a baseball game and a mahjong game — into a single sequence:

Matsumoto makes it seem as if the gambler’s action precipitated the slide into second base. It’s an elegant visual trick that establishes the simultaneity of the two games while suggesting the intensity of the mahjong play; the discarding of a tile is portrayed with the same explosive energy as stealing a base.

Matsumoto makes it seem as if the gambler’s action precipitated the slide into second base. It’s an elegant visual trick that establishes the simultaneity of the two games while suggesting the intensity of the mahjong play; the discarding of a tile is portrayed with the same explosive energy as stealing a base.

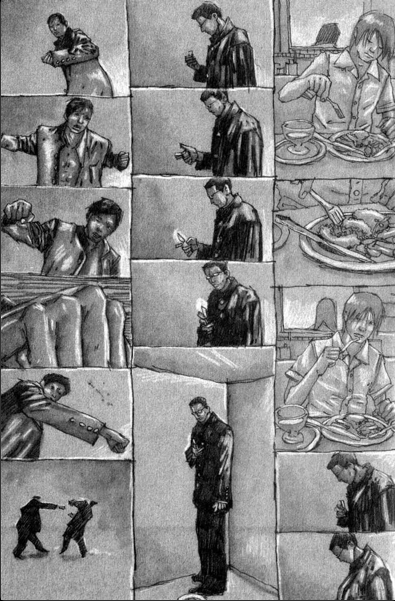

Some of Matsumoto’s time-bending sequences are more cinematic, evoking the kind of split-screen technique popularized in the 1960s by filmmakers like John Frankenheimer and Richard Fleischer. The prologue, for example, contains a series of short, vertical strips in which we see unnamed teenagers preparing for a day at school. Matsumoto deliberates re-frames the activity in each panel, drawing back to show the full scene in some, and pulling in close to reveal the blankness of a characters’ face in another:

It’s an effective montage, largely for the way it juxtaposes the banal with the violent; the fist-fight is presented in the same, matter-of-fact fashion as the student eating breakfast, suggesting that conflict is as routine for some of Blue Spring‘s characters as catching the train to school. The transitions, too, are handled deftly; the eye can process these little vignettes in a sequence while the brain grasps the entire prologue as a simultaneous collage of events, a representative cross-section of high school students going about their business on a typical day.

Matsumoto’s stark, black-and-white imagery won’t be to every reader’s taste; I’d be the first admit that many of the kids in Blue Spring look older and wearier than Keith Richards, with their sunken eyes and rotten teeth. But the studied ugliness of the character designs and urban settings suits the material perfectly, hinting at the anger and emptiness of the characters’ lives. Matsumoto offers no easy answers for his characters’ behavior, nor any false hope that they will escape the lives of violence and despair that seem to be their destiny. Rather, he offers a frank, funny and often disturbing look at the years in which most of us were unformed lumps of clay — or, in Matsumoto’s memorable formulation, a time when most of us were blue: “No matter how passionate you were, no matter how much your blood boiled, I believe youth is a blue time. Blue — that indistinct blue that paints the town before the sun rises.”

This is an expanded version of a review that appeared at PopCultureShock on 4/30/07.

BLUE SPRING • BY TAIYO MATSUMOTO • VIZ • 216 pp. • RATING: MATURE (18+)

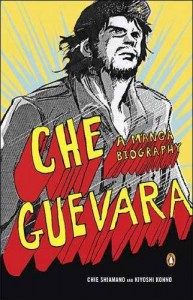

5. Che Guevara: A Manga Biography

5. Che Guevara: A Manga Biography