If you spend any time surfing the mangasphere, you don’t need me to tell you that Twin Spica is about a group of teenagers who are training to become Japan’s first astronauts. You probably know — or have heard from other readers — that it’s poignant. And you may have heard pundits declare it one of the best new series of 2010. (It made my best-of list.) Rather than re-hash plot points or tell you how awesome it is, therefore, I thought I’d share what I like best about Twin Spica: every volume makes me want to look up at the sky.

I’m not talking about the simple act of looking through a telescope or watching clouds drift in the wind — I’m talking about the way the act of looking at the sky makes me feel. Reflecting back on my childhood, that act elicited very specific emotions: the sky represented the future, a large canvas on which I could project my most cherished dreams of traveling to distant places, having adventures, and doing things that, from a six or eight-year-old’s perspective, seemed important. Kou Yaginuma clearly remembers that feeling from his own childhood, because his characters are at their most optimistic and thoughtful when they’re looking up at the sky and thinking about their own experiences.

There’s a lovely moment in volume six, for example, when Fuchuya’s grandfather tells six-year-old Asumi to cherish the memory of gazing up at the sky, as the sky will look different to her as she reaches adulthood. He explains:

You might as well spend your time looking up, at the sky. Me, I’ve spent decades staring up the sky in this town. I only thought the sky was very high when I was your age. When you’re old, it doesn’t seem quite that way. The sky you see as a kid is a lifelong treasure. I mean it. Value what you can see now, and only now.

Reading this passage reminds me of “Feldeinsamkeit” (“In Summerfields”), a beautiful piece of juvenilia from Charles Ives’ 114 Songs. The lyrics, taken from German poet Hermann Allmers, describe the experience of lying in a meadow on a summer’s afternoon and watching the sky. The sight of drifting clouds induces melancholy in his poem’s narrator, who — in typical nineteenth-century fashion — sees the clouds’ gentle, unfettered progress across the sky as a symbol of release from earthly burdens:

I’m resting quietly in tall green grass,

I’m resting quietly in tall green grass,

and cast my eyes far upwards;

around me crickets chirp unceasing,

the sky’s blue magically encloses me.

The beautiful white clouds float past

through the deep blue, like lovely silent dreams.

It is as if I had been long dead,

and flew in bliss with them through unending space.

Ives’ setting, by his own standards, is rather tame; there’s a running accompaniment figure that suggests fast-moving clouds, and a fleeting moment of bitonality, but it falls squarely within the nineteenth-century Stimmungslied tradition with its rounded binary form and gentle chromaticism. The song has an undeniably haunting quality, however. Its rapid modulation to harmonically distant key signatures and achingly sad melodic line suggest that the singer isn’t simply describing the act of watching clouds, as the lyrics alone might imply, but remembering what she was thinking and feeling as she did so.

That may sound like a minor distinction, but memory — or, more accurately, the act of remembering — is an important motif in the 114 Songs. “At the River,” for example, initially sounds like a straightforward rendition of “Shall We Gather At the River,” only to deviate from the melody as the singer “forgets” the proper tune, while “Memories” re-enacts a child’s enthusiasm at attending a concert. “In Summerfields” is less self-consciously modernist than either of these songs, but all three rely heavily on the illusion that the performer is reliving one of her own memories.

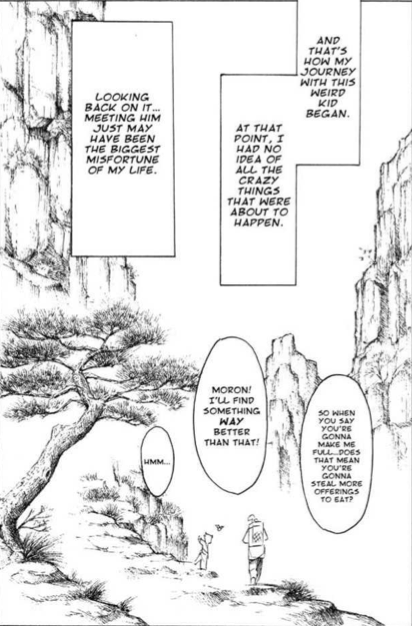

And that’s exactly the quality I find so compelling about Twin Spica: it’s a manga about living with vivid memories — some haunting, some happy — about reconciling past and present, about recognizing the value in both joy and pain, about negotiating the transition from youthful innocence to adulthood. In that scene with Fuchuya’s grandfather, we’re given a powerful reminder of just how much symbolic importance the sky holds for all of us, even if it doesn’t fill us with the same sense of wonder that it did when we were small.

Review copies provided by Vertical, Inc.

TWIN SPICA, VOLS. 5-6 • BY KOU YAGINUMA • VERTICAL, INC. • RATING: TEEN (13+)