It makes me feel good that there are still new series coming out from Viz in the Viz Signature imprint. Sunny by Taiyo Matsumoto is also an addition to the trend of nicely packaged manga hardcovers. With a slightly larger trim size (the same as the other IKKI titles) and color pages before most chapters, this is a volume that will delight manga collectors looking for something nicer than the average paperback. I’ve only read Blue Spring by Matsumoto before, I really need to get around to reading Tekkon Kinkreet.

Sunny is written in one of my favorite fiction formats – a collection of interrelated short stores with shifting main characters that are all tied together. The Sunny of the title of the book refers to a broken down old Nissan Sunny car that sits in the back of a group home for abandoned children. The Sunny is a secret hideout, place to stash porn and other illicit materials, and a means of escape for a group of kids that doesn’t have much security or fun in their daily lives. The volume opens with a brief glimpse of foster home chaos, quickly inter cut with a scene showing the imagination of Haruo, who sits in the car imagining that he’s bleeding out in the desert like a tragic movie tough guy. Haruo’s reverie is abruptly interrupted by Junsuke, an overly hyper snotty-nosed kid who eagerly announces that there’s a new arrival in the house. The readers of Sunny and the new kid Sei both get an abrupt introduction to the children’s home as Sei goes through the house and sits in the Sunny with Haruo and Junsuke. When Sei says that his mom is going to pick him up before summer Haruo says, “No way you’re goin home. You got dumped.”

Sunny captures Haruo’s frustration and anger about his own situation, combined with his helplessness about being able to change anything. Junsuke struggles with his instinct to grab anything shiny, even stealing from his classmates at times. While Haruo is a central viewpoint character, Sunny fluidly moves among different points of view, showing Megumu’s concern for a dead cat and the real-world concerns of older kid Kenji. While there’s a lot of hopelessness in the lives of the kids who live at the home, they also stick up for each other and come together when one of them goes missing.

Matsumoto has a scratchy pen and ink style in his drawings, which incorporate cartoonish elements like circles for rosy cheeks. Washes of ink in varying intensity and hand-drawn textures instead of screentones give Sunny a hand-crafted feel that stands out among more corporate glossy manga. Matsumoto’s detailed backgrounds firmly establish the neighborhood the kids live in, as well as the run-down environment of their house. Overall, Sunny is exactly what I’d expect from the Viz Signature line – a nuanced work that is set apart from more commercial manga due to its artistic and literary value .

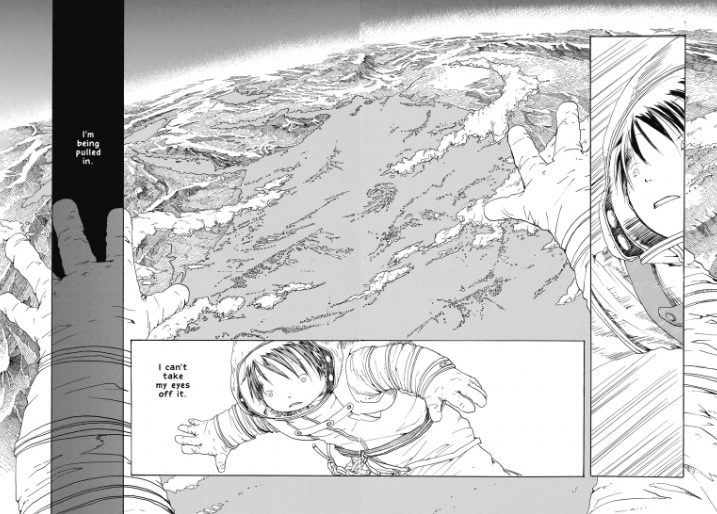

If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.

If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.

Among the most discussed scenes in the new Kick-Ass film is one that pits a tweenage assassin against a roomful of grown men. To the strains of The Banana Splits theme song, thirteen-year-old Hit Girl dispatches a dozen gangsters with a gory zest that has divided critics into two camps: those, like Richard Corliss, who found the scene shocking yet exhilarating, a purposeful, subversive commentary on superhero violence, and those, like Roger Ebert, who found it morally reprehensible, a kind of kiddie porn that exploits the character’s age for cheap thrills. What’s at issue here is not children’s capacity for violence; anyone who’s run the gauntlet of a junior high cafeteria or cranked out an essay on Lord of the Flies is painfully aware that kids can be beastly when the grown-ups aren’t looking. The real issue is that Hit Girl seems to be enjoying herself, raising the far more uncomfortable question of how children understand and wield power.

Among the most discussed scenes in the new Kick-Ass film is one that pits a tweenage assassin against a roomful of grown men. To the strains of The Banana Splits theme song, thirteen-year-old Hit Girl dispatches a dozen gangsters with a gory zest that has divided critics into two camps: those, like Richard Corliss, who found the scene shocking yet exhilarating, a purposeful, subversive commentary on superhero violence, and those, like Roger Ebert, who found it morally reprehensible, a kind of kiddie porn that exploits the character’s age for cheap thrills. What’s at issue here is not children’s capacity for violence; anyone who’s run the gauntlet of a junior high cafeteria or cranked out an essay on Lord of the Flies is painfully aware that kids can be beastly when the grown-ups aren’t looking. The real issue is that Hit Girl seems to be enjoying herself, raising the far more uncomfortable question of how children understand and wield power. Kingyo Used Books starts from a simple premise: an eccentric group of people run a second-hand bookstore in an out-of-the-way location. Various customers stumble upon the shop — usually by accident — and, in the process of browsing, find a manga that helps them reconnect with a part of themselves that’s been suppressed, whether it be a youthful capacity for romantic infatuation or a desire to paint expressively.

Kingyo Used Books starts from a simple premise: an eccentric group of people run a second-hand bookstore in an out-of-the-way location. Various customers stumble upon the shop — usually by accident — and, in the process of browsing, find a manga that helps them reconnect with a part of themselves that’s been suppressed, whether it be a youthful capacity for romantic infatuation or a desire to paint expressively.