I find Natsume Ono’s work rewarding and maddening in equal measure. On the plus side, I love her idiosyncratic style; her panels are spare and elegantly composed, with just enough detail to convey the story’s time and place. Her character designs, too, are a welcome departure from the youthful, homogenized look of mainstream shojo and shonen manga. Her people have sharp features and rangy bodies, yet inhabit their skins as comfortably as the proverbial pair of old shoes; it’s rare to see middle age depicted so gracefully. And speaking of middle age, her characters’ maturity is another plus, as they grapple with the kind of real-world problems — failed marriages, aging parents, child-rearing — that are almost never addressed in manga licensed for the US market.

I find Natsume Ono’s work rewarding and maddening in equal measure. On the plus side, I love her idiosyncratic style; her panels are spare and elegantly composed, with just enough detail to convey the story’s time and place. Her character designs, too, are a welcome departure from the youthful, homogenized look of mainstream shojo and shonen manga. Her people have sharp features and rangy bodies, yet inhabit their skins as comfortably as the proverbial pair of old shoes; it’s rare to see middle age depicted so gracefully. And speaking of middle age, her characters’ maturity is another plus, as they grapple with the kind of real-world problems — failed marriages, aging parents, child-rearing — that are almost never addressed in manga licensed for the US market.

On the minus side, Ono’s artwork is an acquired taste; the reader sometimes has to take it on faith that a particular character is handsome or pretty, as Ono’s children and twenty-somethings are less persuasively realized than her older characters. Then, too, Ono’s fondness for depicting everyday moments can rob her stories of any meaningful dramatic shape, creating long, meandering stretches where very little happens and even less is revealed about the characters. More frustrating still is her tendency to vacillate between allowing readers to interpret events for themselves and slapping readers across the face with a pointed observation, as if she doesn’t trust the audience to read the scene properly without a little authorial intervention.

…

House of Five Leaves, too, focuses less on Big Events and more on everyday activity, but in Leaves, Ono’s restraint serves an important dramatic purpose: she’s showing us events through Masanosuke’s eyes, as he tries to reconcile the bandits’ seemingly ordinary lives with their extraordinary behavior. Making the reader‘s task more difficult is that Masanosuke isn’t very astute. He tends to focus on a kind gesture or a friendly conversation, missing many of the important aural and visual cues that might enable him to understand what’s happening — a trait that the group exploits. In one chapter, for example, Yaichi encourages Masanosuke to accept a job as a bodyguard for a merchant family while the group plans its next kidnapping. Masa befriends his new employer’s son, never realizing that his true assignment is to infiltrate the target’s household so that Yaichi’s minions can snatch the boy for ransom.

House of Five Leaves, too, focuses less on Big Events and more on everyday activity, but in Leaves, Ono’s restraint serves an important dramatic purpose: she’s showing us events through Masanosuke’s eyes, as he tries to reconcile the bandits’ seemingly ordinary lives with their extraordinary behavior. Making the reader‘s task more difficult is that Masanosuke isn’t very astute. He tends to focus on a kind gesture or a friendly conversation, missing many of the important aural and visual cues that might enable him to understand what’s happening — a trait that the group exploits. In one chapter, for example, Yaichi encourages Masanosuke to accept a job as a bodyguard for a merchant family while the group plans its next kidnapping. Masa befriends his new employer’s son, never realizing that his true assignment is to infiltrate the target’s household so that Yaichi’s minions can snatch the boy for ransom. ORANGE PLANET, VOL. 1

ORANGE PLANET, VOL. 1 Orange Planet, Vol. 1

Orange Planet, Vol. 1 Red Hot Chili Samurai, Vol. 1

Red Hot Chili Samurai, Vol. 1 Togainu no Chi, Vol. 1

Togainu no Chi, Vol. 1  In Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics, author Paul Gravett argues that female mangaka from Riyoko Ikeda to CLAMP have often used “the fluidity of gender boundaries and forbidden love” to “address issues of deep importance to their readers.” Taeko Watanabe is no exception to the rule, employing cross-dressing and shonen-ai elements to tell a story depicting the “pressures and pleasures of individuals living life in their own way and, for better or worse, not always as society expects.”

In Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics, author Paul Gravett argues that female mangaka from Riyoko Ikeda to CLAMP have often used “the fluidity of gender boundaries and forbidden love” to “address issues of deep importance to their readers.” Taeko Watanabe is no exception to the rule, employing cross-dressing and shonen-ai elements to tell a story depicting the “pressures and pleasures of individuals living life in their own way and, for better or worse, not always as society expects.” THE FOUR IMMIGRANTS MANGA: A JAPANESE EXPERIENCE IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1904 – 1924

THE FOUR IMMIGRANTS MANGA: A JAPANESE EXPERIENCE IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1904 – 1924 The Four Immigrants Manga

The Four Immigrants Manga Parasyte

Parasyte Satsuma Gishiden

Satsuma Gishiden Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms

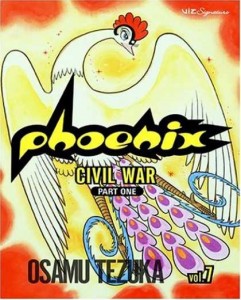

Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War

BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War