InuYasha was the first comic that I actively collected, the manga that introduced me to the Wednesday comic-buying ritual and the very notion of self-identifying as a fan. Though I followed it religiously for years, trading in my older editions for new ones, watching the anime, and speculating about the finale, my interest in the series gradually waned as I was exposed to new artists and new genres. Still, InuYasha held a special place in my heart; reading it was one of my seminal experiences as a comic fan, making me reluctant to re-visit InuYasha for fear of sullying those precious first-manga memories. VIZ’s recent decision to re-issue InuYasha in an omnibus edition, however, inspired me to pick it up again. I made a shocking discovery in the process of re-reading the first chapters: InuYasha is good. Really good, in fact, and deserving of more respect than it gets from many critics.

What makes InuYasha work? I can think of five reasons:

1. The story arcs are long enough to be complex and engaging, but not so long as to test the patience.

There’s a Zen quality to Rumiko Takahashi’s storytelling that might not be obvious at first glance; after all, she loves a pratfall or a sword fight as much as the next shonen manga-ka. Don’t let that surface activity fool you, however: Takahashi has a terrific sense of balance, staging a romantic interlude between a demon-of-the-week episode and a longer storyline involving Naraku’s minions, thus preventing the series from devolving into a punishing string of battle arcs. The other great advantage of this approach is that Takashi carves out more space for her characters to interact as people, not just combatants; as a result, InuYasha is one of the few shonen manga in which the characters’ relationships evolve over time.

2. Takahashi knows how to stage a fight scene that’s dramatic, tense, and mercifully short.

‘Nuff said.

3. InuYasha‘s villains are powerful and strange, not strawmen.

Though we know our heroes will prevail — it’s shonen, for Pete’s sake — Takahashi throws creative obstacles in their way that makes their eventual triumph more satisfying. Consider Naraku. In many respects, he’s a standard-issue bad guy: he’s omnipotent, charismatic, and manipulative, capable of finding the darkness and vulnerability in the purest soul. (He also has fabulous hair, another reliable indication of his villainy.) Yet the way in which Naraku wields power is genuinely unsettling, as he fashions warriors from pieces of himself, then reabsorbs them into his body when they outlive their usefulness. Naraku’s manifestations are peculiar, too. Some are female, some are children, some have monstrous bodies, and some have the power to create their own demonic offspring, but few look like the sort of golem I’d create if I wanted to wreak havoc. And therein lies Naraku’s true power: his opponents never know what form he’ll take next, or whether he’s already among them.

Sesshomaru, too, is another villain who proves more interesting than he first appears. In the very earliest chapters of the manga, he’s a bored sociopath who has no qualms about using InuYasha’s mama trauma to trick his younger brother into revealing the Tetsusaiga’s location. As the story progresses, however, Sesshomaru begins tolerating the company of a cheerful eight-year-old girl who, in a neat inversion of the usual human-canine relationship, is dependent on her dog-demon master for protection, food, and companionship. Takahashi resists the urge to fully “humanize” Sesshomaru, however; he remains InuYasha’s scornful adversary for most of the series, largely unchanged by his peculiar fixation with Rin.

And did I mention that Sesshomaru has awesome hair? Oh, to be a villain in a Takahashi manga!

4. InuYasha‘s female characters kick ass.

Back in 2008, Shaenon Garrity wrote a devastatingly funny article about the seven types of female characters in shonen manga, from The Tomboy to The Little Girl to The Experienced Older Woman. I’m pleased to report that none of these types appear in InuYasha; in fact, InuYasha boasts one of the smartest, toughest, and most appealing set of female characters in shonen manga. And by “tough,” I don’t mean that Kagome, Kikyo, and Sango brandish weapons while wearing provocative outfits; I mean they persist in the face of adversity, even if their own lives are at stake. They’re strong enough to hold their own against demons, ghosts, and heavily armed bandits, and wise enough to know when words are more effective than weapons. They’re not adverse to the idea of romance, but recovering the Shikon Jewel takes precedence over dating. And they’re woman enough to cry if something awful happens, though they’d rather shed their tears in private than show their pain to others.

5. The horror! The horror!

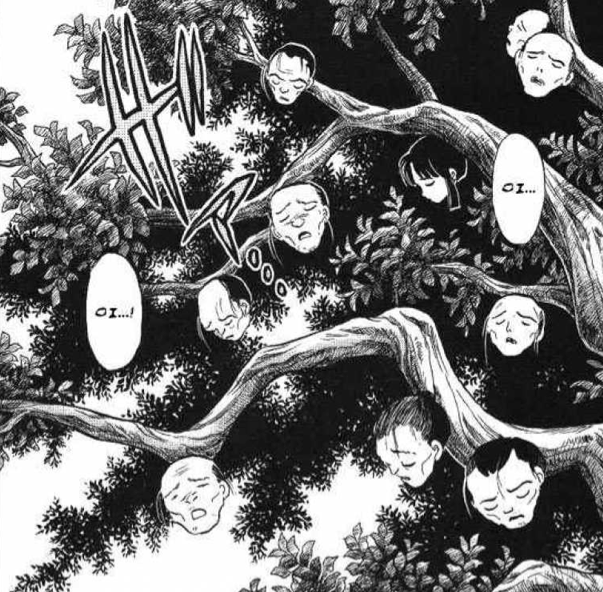

Takahashi may have the coolest resume of anyone working in manga today; not only did she study script writing with Kazuo Koike, she also worked as an assistant to Kazuo Umezu — an apprenticeship that’s evident in the early chapters of InuYasha. In between Kagome and InuYasha’s first encounters with Naraku are a handful of short but spooky stories in which seemingly benign objects — a noh mask, a peach tree — are transformed by Shikon Jewel shards into instruments of torture and killing. Takahashi’s horror stories are less florid than Umezu’s, with fewer detours into WTF? territory, but like Umezu, Takahashi has a vivid imagination that yields some decidedly scary images. Here, for example, is the demonic peach tree from chapter 79, “The Fruits of Evil”:

Takahashi doesn’t just use these images to shock; she uses them to illustrate the consequences of ugly emotions, impulsive actions, and violent behavior, to show us how these choices slowly corrode the soul and transform us into the most monstrous version of ourselves. (Also to show us the consequences of substituting human bones and blood for Miracle Gro. Kids, don’t try this at home.)

What Takahashi does better than almost anyone is walk the fine line between terror and horror. Gothic novelist Ann Radcliffe, author of The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and The Italian (1797), was one of the first writers to argue that terror and horror were different states of arousal. “Terror and Horror are so far opposite, that the first expands the soul and awakens the faculties to a high degree of life; the other contracts, freezes and nearly annihilates them,” she wrote in an 1826 essay, “On the Supernatural in Poetry.” Critiquing Radcliffe’s work in 1966, Devendra P. Varma explained that difference more concretely: “The difference between Terror and Horror is the difference between awful apprehension and sickening realization: between the smell of death and stumbling against a corpse.” And that’s exactly where Takahashi operates: she gives us tantalizing, suggestive glimpses of scary things, then keeps them obscured until the denouement of the story, allowing our imaginations to supply most of the grisly details. We read her work in a heightened state of awareness, which only intensifies our pleasure — and revulsion — when the true nature of Kagome and InuYasha’s foes are revealed.

* * * * *

If you haven’t looked at InuYasha in a while, or missed it during the height of its popularity, now is a great time to give it a try. Each volume of the VIZBIG edition collects three issues, allowing readers to more fully immerse themselves in the story. And if you’re a purist about packaging, you’ll be happy to know that VIZ is finally issuing InuYasha in an unflipped format — a first in the series’ US history.