Back in 2006, I stumbled across this entry at Otaku Champloo, reflecting on the need for a manga “canon.” The author noted that books in the Western literary canon (e.g. Aeschylus, Dante, Shakespeare) were not the “most popular” titles, but titles that “reflect[ed] the progress of humanity” from classical antiquity to the machine age. She then posed several intriguing questions:

[W]hat really struck my head was the idea of a canon for manga. Could we come up a list of mangas that would best represent humanity and the manga genre? Another interesting question would be… what good would a manga canon bring? Does the world of manga need one?

When I first responded to her essay back in 2006, I hadn’t read very much manga — just enough to be dangerously opinionated and scornful of shojo* — and my knowledge of “classic” titles was limited to a few works by Osamu Tezuka and Kazuo Koike. I thought it would be an interesting challenge to revisit and revise that initial response to reflect where I am now, three years and hundreds of series later.

TO INCLUDE OR NOT TO INCLUDE, THAT IS THE QUESTION

As I noted in my initial response, I used to teach at a university that organizes its undergraduate curriculum around the idea that certain works of art, literature, music, and philosophy represent the acme of Western civilization. You might think that the list of canonic works would be fixed, but in fact, the canon is constantly evolving. When the university first mandated its “great works” curriculum in the 1920s, for example, Mary Wollenstonecraft didn’t make the cut; only with the rise of feminist scholarship in the 1970s was her groundbreaking Vindication of the Rights of Woman added to the canon. The 1980s prompted a similar round of revisions to the curriculum: realizing that its emphasis on Western culture excluded some of the oldest and most influential literature in the world, the university developed courses about the canonic work of Eastern civilizations: The Art of War, The Tale of Genji, The Shahnameh.

I cite these curriculum changes because they remind us that defining a canon is a tricky business. There’s a veritable cottage industry of think-tanks and self-appointed cultural guardians who view the inclusion of new voices as a threat to the integrity of the literary canon, as if the recognition that women and blacks have written important books might undermine the point of the whole exercise. (They generally fuss less about Great Art and Great Music, though more conservative scholars in those fields police these canons with a similar zeal: Clara Schumann, hit the road!) In their eyes, the canon is a super-exclusive night club open only to a few “universally” recognized authors; they reject the notion that scholars might have valid historical reasons for admitting a few more folks past the velvet rope.

Then there’s that pesky issue of relevance. My students were always shocked that our music survey didn’t include familiar composers like Tchaikovsky: if we were still performing The Nutcracker and Swan Lake, why wasn’t he taking his rightful place alongside Hildegaard of Bingen and Anton Webern, two composers that 98% of them had never heard of before taking my class? As a music historian, I could rebut their arguments, but my students had a point: sometimes we become so obsessed with the idea that a canon represents the best, most timeless products of a culture that we forget the extent to which taste and connoisseurship play a role in deciding what to include — and what to exclude. (Poor old Tchaikovsky is just too tacky for some scholars, I guess.) We ignore that distinction at our own peril, however, as a canon can become a self-perpetuating list impervious to criticism or revision. Anyone intent on making a list of manga masterpieces, therefore, should bear in mind these observations about how and why we create canons — observations drawn from own experiences studying one of the most canon-centric fields, music.

First, historians play a major role in deciding what works make the cut. This is what I call the “Bach” rule: by the time J. S. Bach was writing his best-known works, his style was seen as old-fashioned, even a little stodgy, and not something an up-and-coming composer would want to emulate. Yet 250 years later, Bach is a household name. Why? Because Bach was “discovered” in the nineteenth century by prominent historians and composers who admired the rigor of his counterpoint and the beauty of his compositions. As a result, he became one of the most studied and posthumously influential composers in Western history. I say this not to slight Bach, or to perpetuate Romantic notions of genius (“they only appreciate you after you’re dead!”), but to remind any would-be canon-builders that an artist’s role in advancing the medium is often the most important rationalization for including his work in a canon.

Second, scholars tend to be suspicious of artists whose work is genuinely popular. This is what I call the “Rachmaninoff” rule: audiences may flock to performances of the Second Piano Concerto, but the canon’s gate-keepers treat Rachmaninoff as “just” a tunesmith whose crowd-pleasing melodies lack the harmonic or structural sophistication of Stravinsky and Wagner’s best work. Rachmaninoff’s tenuous membership in the canon reflects our lingering skepticism about popularity: if everyone likes Rachmaninoff’s music, could it really as worthy of study and emulation as music that aspires to greater levels of compositional complexity (e.g. The Rite of Spring, Parsifal)? It’s the same impulse that might lead a manga scholar to include Tezuka’s Buddha in the canon while excluding Kishimoto’s Naruto or Takahashi’s Ranma 1/2 — we wouldn’t want the “merely” popular taking its place alongside bonafide masterpieces, would we?

Third, there is no such thing as a “universal” canon. This is what I call the “Gershwin” rule. From the perspective of an American historian, George Gershwin is a canonic composer, profoundly influencing the development of American music with his distinctive marriage of black vernacular styles to European art forms. But from a Russian or Italian perspective, Gershwin is a local anomaly, a decent American composer who enjoys a far greater reputation among his fellow countrymen than in the international community. (Translation: he ain’t no Stravinsky or Verdi.) As such, Gershwin is less likely to be mentioned by an Italian musicologist in the same breath as Rossini, Verdi, or Beethoven. Undoubtedly, there will be artists whose importance to Americans may make them obvious candidates for inclusion in a manga canon, but who may not be viewed as favorably on the other side of the Pacific (and vice versa, I might add).

Finally, there is no such thing as an opera or a novel or a manga that is timeless. This is what I call the “Don Giovanni” rule: we still perform Mozart’s opera 200+ years after its initial premiere, but our experience of Don Giovanni is utterly different than that of audiences who heard it 1787. Most of the opera’s musical “in jokes,” for example, are lost on us—how many of us would recognize Mozart’s shout-out to fellow composer Martin y Soler? And how many of us would grasp the subtle musical gestures that Mozart uses to indicate his characters’ social status—gestures that were old hat to his audience? It’s a safe bet that Osamu Tezuka’s current audience experiences his work differently than its original readers, even though we may admire some of the same qualities in his work as the first generation of Princess Knight and Astro Boy fans.

Is there a need for a similar “canon” of manga masterpieces? The growing body of literature on influential artists such as Osamu Tezuka suggests that scholars already entertain some notion of a manga canon. As we begin labeling works “masterpieces,” however, we need to be mindful of the way in which these labels can trap us, preventing us from critiquing or questioning, say, Tatsumi or Tezuka’s greatness. We also need to remember that whatever canon we devise will be flawed from the outset, revised many times, and say as much about our own tastes and values as it will about the inherent quality or relevance of the manga it includes.

POSTSCRIPT

Having identified several potential pitfalls of canonization (if I might re-purpose that term for non-Vatican usage), I’m curious to know (a) whether it makes sense to talk about a manga “canon” and (b) what titles and authors you think belong in the canon. I’m particularly interested in the issue of gender: what female manga-ka belong in a canon and why? Do we have an innate bias towards seinen works, to the exclusion of shojo and josei titles? Inquiring minds want to know!

UPDATE, 9/15/09: Over at Extremely Graphic, librarian-blogger Sadie Maddox offers a thoughtful response to the question of whether or not Americans even have any business talking about a “manga canon.” She notes:

By being translated the integrity of the original work is compromised. Of course, I’m all for translating because it means I get to read manga and I know that most translators do an excellent job. But still, that’s one layer removed from the original intent. Are Americans really the ones who should be making a canon out of completely foreign material?

I didn’t get into the issue of translation (obviously one that would need to be addressed, if we were going to take this exercise to its logical conclusion), so go, read, and join the discussion at Extremely Graphic.

UPDATE, 10/6/09: Scholars John E. Ingulsrud and Kate Allen, authors of Reading Japan Cool: Patterns of Manga Literacy and Discourse, posted an interesting response to the question, “What belongs in the manga canon?” Their argument hinges on pedagogy: they note the original purpose of a canon was “to teach and test,” citing the New Testament as a body of literature compiled, in part, to answer the question, “Who was Jesus?” They suggest that any manga canon will arise from a similar need to teach and test. I think that’s a valid argument for the Japanese academy, but is more problematic in a Western context; it’s simply too early to know whether manga will be a permanent part of the American cultural landscape or just a passing fad. I also think they’re too quick to dismiss the question of artistry, as one of the most important contemporary functions of the so-called Western canon — by which I mean literature, art, and music — is to teach aesthetics. Whatever my philosophical differences with Ingulrud and Allen, I found their historical arguments compelling, and encourage you to read their essay for a different perspective on the issue of canonicity.

Highbrow, lowbrow… and everything in between. That’s the slogan of

Highbrow, lowbrow… and everything in between. That’s the slogan of  In the year 2346 A.D., humans have colonized the Vulcan solar system, a region so inhospitable that the average life span is a mere thirty years. Rai and Thor, whose parents belong to Vulcan’s ruling elite, enjoy a life of rare privilege — that is, until a political rival executes their parents and exiles the boys to Kimaera, a penal colony reserved for violent criminals. To say Kimaera’s climate is harsh understates the case: daylight lasts for 181 days, producing extreme desert conditions and water shortages, while nighttime plunges Kimaera into arctic darkness for an equal length of time. Making the place even more treacherous is the flora, as Kimaera’s jungles team with carnivorous plants capable of eating humans whole.

In the year 2346 A.D., humans have colonized the Vulcan solar system, a region so inhospitable that the average life span is a mere thirty years. Rai and Thor, whose parents belong to Vulcan’s ruling elite, enjoy a life of rare privilege — that is, until a political rival executes their parents and exiles the boys to Kimaera, a penal colony reserved for violent criminals. To say Kimaera’s climate is harsh understates the case: daylight lasts for 181 days, producing extreme desert conditions and water shortages, while nighttime plunges Kimaera into arctic darkness for an equal length of time. Making the place even more treacherous is the flora, as Kimaera’s jungles team with carnivorous plants capable of eating humans whole. Though the story is well-executed, the artwork is something of a disappointment. Itsuki goes to great pains to create a diverse cast — a task at which she’s generally successful — but her character designs are generic and dated; I’d be hard-pressed to distinguish the Kimaerans from, say, the cast of RG Veda or Basara. Itsuki also struggles with skin color; her dark-skinned women bear an unfortunate resemblance to kogals, thanks to Itsuki’s clumsy application of screentone.

Though the story is well-executed, the artwork is something of a disappointment. Itsuki goes to great pains to create a diverse cast — a task at which she’s generally successful — but her character designs are generic and dated; I’d be hard-pressed to distinguish the Kimaerans from, say, the cast of RG Veda or Basara. Itsuki also struggles with skin color; her dark-skinned women bear an unfortunate resemblance to kogals, thanks to Itsuki’s clumsy application of screentone. Tegami Bachi has all the right ingredients to be a great shonen series: a dark, futuristic setting; rad monsters; cool weapons powered by mysterious energy sources; characters with goofy names (how’s “Gauche Suede” grab you?); and smart, stylish artwork. Unfortunately, volume one seems a little underdone, like a piping-hot shepherd’s pie filled with rock-hard carrots.

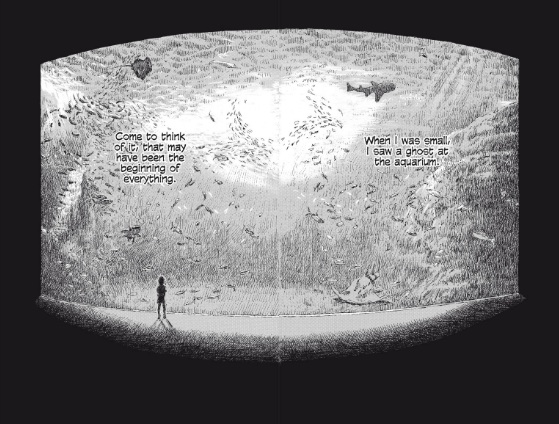

Tegami Bachi has all the right ingredients to be a great shonen series: a dark, futuristic setting; rad monsters; cool weapons powered by mysterious energy sources; characters with goofy names (how’s “Gauche Suede” grab you?); and smart, stylish artwork. Unfortunately, volume one seems a little underdone, like a piping-hot shepherd’s pie filled with rock-hard carrots. The ocean occupies a special place in the artistic imagination, inspiring a mixture of awe, terror, and fascination. Watson and the Shark, for example, depicts the ocean as the mouth of Hell, a dark void filled with demons and tormented souls, while The Birth of Venus offers a more benign vision of the ocean as a life-giving force. In Children of the Sea, Daisuke Igarashi imagines the ocean as a giant portal between the terrestrial world and deep space, as is suggested by a refrain that echoes throughout volume one:

The ocean occupies a special place in the artistic imagination, inspiring a mixture of awe, terror, and fascination. Watson and the Shark, for example, depicts the ocean as the mouth of Hell, a dark void filled with demons and tormented souls, while The Birth of Venus offers a more benign vision of the ocean as a life-giving force. In Children of the Sea, Daisuke Igarashi imagines the ocean as a giant portal between the terrestrial world and deep space, as is suggested by a refrain that echoes throughout volume one:

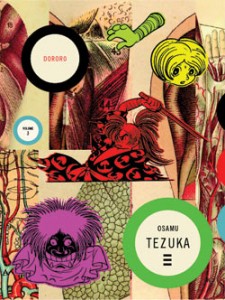

If Phoenix is Tezuka’s Ring Cycle, Wagnerian in scope, form, and seriousness, then Dororo is Tezuka’s Don Giovanni, a playful marriage of supernatural intrigue and lowbrow comedy whose deeper message is cloaked in shout-outs to fellow artists (in this case,

If Phoenix is Tezuka’s Ring Cycle, Wagnerian in scope, form, and seriousness, then Dororo is Tezuka’s Don Giovanni, a playful marriage of supernatural intrigue and lowbrow comedy whose deeper message is cloaked in shout-outs to fellow artists (in this case,  Though much of the devastation that Hyakkimaru and Dororo witness is man-made (Dororo takes placed during the Sengoku, or Warring States, Period), demons exploit the conflict for their own benefit, holding small communities in their thrall, luring desperate travelers to their doom, and feasting on the never-ending supply of human corpses. Some of these demons have obvious antecedents in Japanese folklore — a nine-tailed kitsune — while others seem to have sprung full-blown from Tezuka’s imagination — a shark who paralyzes his victims with sake breath, a demonic toad, a patch of mold possessed by an evil spirit. (As someone who’s lived in prewar buildings, I can vouch for the existence of demonic mold. Lysol is generally more effective than swordplay in eliminating it, however.) Hyakkimaru has a vested interest in killing these demons, as he spontaneously regenerates a lost body part with each monster he slays. But he also feels a strong sense of kinship with many victims — a feeling not shared by those he helps, who cast him out of their village as soon as the local demon has been vanquished.

Though much of the devastation that Hyakkimaru and Dororo witness is man-made (Dororo takes placed during the Sengoku, or Warring States, Period), demons exploit the conflict for their own benefit, holding small communities in their thrall, luring desperate travelers to their doom, and feasting on the never-ending supply of human corpses. Some of these demons have obvious antecedents in Japanese folklore — a nine-tailed kitsune — while others seem to have sprung full-blown from Tezuka’s imagination — a shark who paralyzes his victims with sake breath, a demonic toad, a patch of mold possessed by an evil spirit. (As someone who’s lived in prewar buildings, I can vouch for the existence of demonic mold. Lysol is generally more effective than swordplay in eliminating it, however.) Hyakkimaru has a vested interest in killing these demons, as he spontaneously regenerates a lost body part with each monster he slays. But he also feels a strong sense of kinship with many victims — a feeling not shared by those he helps, who cast him out of their village as soon as the local demon has been vanquished. For folks who find the cartoonish aspects of Tezuka’s style difficult to reconcile with the serious themes addressed in Buddha, Phoenix, and Ode to Kirihito, Dororo may prove a more satisfying read. The cuteness of Tezuka’s heroes actually works to his advantage; they seem terribly vulnerable when contrasted with the grotesque demons, ruthless samurai, and scheming bandits they encounter. Tezuka’s jokes — which can be intrusive in other stories — also prove essential to Dororo‘s success. He shatters the fourth wall, inserts characters from his stable of “stars,” borrows characters from other manga-kas’ work, and punctuates moments of high drama with low comedy, underscoring the sheer absurdity of his conceits… like sake-breathing shark demons. Put another way, Dororo wears its allegory lightly, focusing primarily on swordfights, monster lairs, and damsels in distress while using its historical setting to make a few modest points about the corrosive influence of greed, power, and fear.

For folks who find the cartoonish aspects of Tezuka’s style difficult to reconcile with the serious themes addressed in Buddha, Phoenix, and Ode to Kirihito, Dororo may prove a more satisfying read. The cuteness of Tezuka’s heroes actually works to his advantage; they seem terribly vulnerable when contrasted with the grotesque demons, ruthless samurai, and scheming bandits they encounter. Tezuka’s jokes — which can be intrusive in other stories — also prove essential to Dororo‘s success. He shatters the fourth wall, inserts characters from his stable of “stars,” borrows characters from other manga-kas’ work, and punctuates moments of high drama with low comedy, underscoring the sheer absurdity of his conceits… like sake-breathing shark demons. Put another way, Dororo wears its allegory lightly, focusing primarily on swordfights, monster lairs, and damsels in distress while using its historical setting to make a few modest points about the corrosive influence of greed, power, and fear. Since childhood, Misao has been cursed with an unlucky gift: the ability to see ghosts and demons. As her sixteenth birthday approaches, however, Misao’s luck begins to change. Isayama, the star of the tennis team, asks her out, and Kyo, a childhood friend, moves into the house next door, pledging to protect Misao from harm. Kyo’s promise is quickly put to the test when Isayama turns out to be a blood-thirsty demon who’s intent on killing — and eating — Misao. Just before Isayama attacks Misao, he tells her that she’s “the bride of prophecy”: drink her blood, and a demon will gain strength; eat her flesh, and he’ll enjoy eternal youth; marry her, and his whole clan will flourish. Kyo rescues Misao, revealing, in the process, that he himself is a tengu (winged demon) who’s also jonesing for her blood. Kyo then offers her a choice: marry him or die. Actually, Kyo is less tactful than that, telling Misao, “You can be eaten, or you can sleep with me and become my bride.”

Since childhood, Misao has been cursed with an unlucky gift: the ability to see ghosts and demons. As her sixteenth birthday approaches, however, Misao’s luck begins to change. Isayama, the star of the tennis team, asks her out, and Kyo, a childhood friend, moves into the house next door, pledging to protect Misao from harm. Kyo’s promise is quickly put to the test when Isayama turns out to be a blood-thirsty demon who’s intent on killing — and eating — Misao. Just before Isayama attacks Misao, he tells her that she’s “the bride of prophecy”: drink her blood, and a demon will gain strength; eat her flesh, and he’ll enjoy eternal youth; marry her, and his whole clan will flourish. Kyo rescues Misao, revealing, in the process, that he himself is a tengu (winged demon) who’s also jonesing for her blood. Kyo then offers her a choice: marry him or die. Actually, Kyo is less tactful than that, telling Misao, “You can be eaten, or you can sleep with me and become my bride.” When I was applying to college, my guidance counselor encouraged me to compose a list of amenities that my dream school would have — say, a first-class orchestra or a bucolic New England setting. It never occurred to me to add “pet-friendly dormitories” to that list, but reading Yuji Iwahara’s Cat Paradise makes me wish I’d been a little more imaginative in my thinking. The students at Matabi Academy, you see, are allowed to have cats in the dorms, a nice perk that has a rather sinister rationale: cats play a vital role in defending the school against Kaen, a powerful demon who’s been sealed beneath its library for a century.

When I was applying to college, my guidance counselor encouraged me to compose a list of amenities that my dream school would have — say, a first-class orchestra or a bucolic New England setting. It never occurred to me to add “pet-friendly dormitories” to that list, but reading Yuji Iwahara’s Cat Paradise makes me wish I’d been a little more imaginative in my thinking. The students at Matabi Academy, you see, are allowed to have cats in the dorms, a nice perk that has a rather sinister rationale: cats play a vital role in defending the school against Kaen, a powerful demon who’s been sealed beneath its library for a century. Nineteen sixty-eight was a critical year in Osamu Tezuka’s artistic development. Best known as the creator of Astro Boy, Jungle Emperor Leo, and Princess Knight, the public viewed Tezuka primarily as a children’s author. That assessment of Tezuka wasn’t entirely warranted; he had, in fact, made several forays into serious literature with adaptations of Manon Lescaut (1947), Faust (1950), and Crime and Punishment (1953). None of these works had made a lasting impression, however, so in 1968, as gekiga was gaining more traction with adult readers, Tezuka adopted a different tact, writing a dark, erotic story for Big Comic magazine: Swallowing the Earth.

Nineteen sixty-eight was a critical year in Osamu Tezuka’s artistic development. Best known as the creator of Astro Boy, Jungle Emperor Leo, and Princess Knight, the public viewed Tezuka primarily as a children’s author. That assessment of Tezuka wasn’t entirely warranted; he had, in fact, made several forays into serious literature with adaptations of Manon Lescaut (1947), Faust (1950), and Crime and Punishment (1953). None of these works had made a lasting impression, however, so in 1968, as gekiga was gaining more traction with adult readers, Tezuka adopted a different tact, writing a dark, erotic story for Big Comic magazine: Swallowing the Earth.