After reading Missin’ and Missin’ 2, I’m convinced that novelist Novala Takemoto was a teenage girl in a previous life. But not the kind of girl who was on the cheerleading squad, the volleyball team, or the school council — no, Takemoto was the too-cool-for-school girl, the one whose unique fashion sense, sullen demeanor, and indifference to high school mores made her seem more adult than her peers, even if her behavior and emotions were, in fact, just as juvenile as everyone else’s. Though this kind of angry female rebel is a stock character in young adult novels, Takemoto has a special gift for making them sound like real girls, not an adult’s idea of what a disaffected teenager sounds like.

After reading Missin’ and Missin’ 2, I’m convinced that novelist Novala Takemoto was a teenage girl in a previous life. But not the kind of girl who was on the cheerleading squad, the volleyball team, or the school council — no, Takemoto was the too-cool-for-school girl, the one whose unique fashion sense, sullen demeanor, and indifference to high school mores made her seem more adult than her peers, even if her behavior and emotions were, in fact, just as juvenile as everyone else’s. Though this kind of angry female rebel is a stock character in young adult novels, Takemoto has a special gift for making them sound like real girls, not an adult’s idea of what a disaffected teenager sounds like.

Consider Kasako, the heroine of Missin’ and Missin’ 2. Kasako feels estranged from her peers’ pop-culture interests, finding refuge in “the antique, the outmoded, indeed, the passe.” Though she has a special affinity for Schubert lieder and Rococo artwork, she finds a kindred spirit in Nobuko Yoshiya, a popular romance novelist whose career spanned the Taisho and Showa periods. Like an earlier generation of schoolgirls, Kasako is enthralled with Yoshiya’s Hana monogatari (Tales of the Flower, 1916 – 1924), a pioneering work of Class S fiction, or stories about romantic friendships between teenage girls.

…

Built in 1607, the Ooku, or “great interior,” housed the women of the Tokugawa clan, from the shogun’s mother to his wife and concubines. Strict rules prevented residents from fraternizing with outsiders, or leaving the grounds of Edo Castle without permission. Within the Ooku, an elaborate hierarchy governed day-to-day life; at the very top were the joro otoshiyori, or senior elders, who supervised the shogun’s attendants and served as court liaisons; beneath them were a web of concubines, priests, pages, cooks, and char women who hailed from politically connected families. This elaborate social system was mirrored in the physical structure of the Ooku, which was divided into three distinct areas — the Rear Quarters, the Middle Interior, and the Front Quarters — each intended solely ladies of a particular rank. The only male permitted into the Ooku (unescorted, that is), was the shogun himself, who accessed the “great interior” by means of the Osuzu Roka, a long corridor that connected the shogun’s living quarters with the imperial harem.

Built in 1607, the Ooku, or “great interior,” housed the women of the Tokugawa clan, from the shogun’s mother to his wife and concubines. Strict rules prevented residents from fraternizing with outsiders, or leaving the grounds of Edo Castle without permission. Within the Ooku, an elaborate hierarchy governed day-to-day life; at the very top were the joro otoshiyori, or senior elders, who supervised the shogun’s attendants and served as court liaisons; beneath them were a web of concubines, priests, pages, cooks, and char women who hailed from politically connected families. This elaborate social system was mirrored in the physical structure of the Ooku, which was divided into three distinct areas — the Rear Quarters, the Middle Interior, and the Front Quarters — each intended solely ladies of a particular rank. The only male permitted into the Ooku (unescorted, that is), was the shogun himself, who accessed the “great interior” by means of the Osuzu Roka, a long corridor that connected the shogun’s living quarters with the imperial harem.

Tegami Bachi has all the right ingredients to be a great shonen series: a dark, futuristic setting; rad monsters; cool weapons powered by mysterious energy sources; characters with goofy names (how’s “Gauche Suede” grab you?); and smart, stylish artwork. Unfortunately, volume one seems a little underdone, like a piping-hot shepherd’s pie filled with rock-hard carrots.

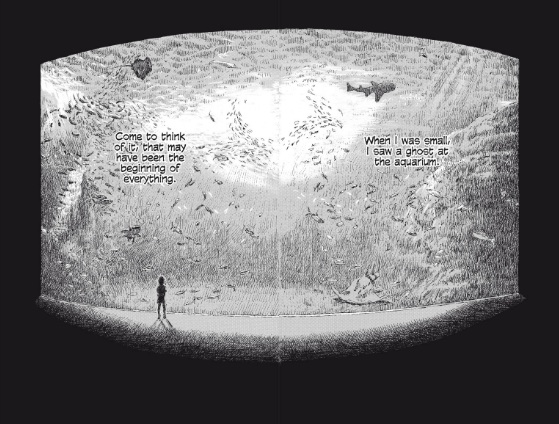

Tegami Bachi has all the right ingredients to be a great shonen series: a dark, futuristic setting; rad monsters; cool weapons powered by mysterious energy sources; characters with goofy names (how’s “Gauche Suede” grab you?); and smart, stylish artwork. Unfortunately, volume one seems a little underdone, like a piping-hot shepherd’s pie filled with rock-hard carrots. The ocean occupies a special place in the artistic imagination, inspiring a mixture of awe, terror, and fascination. Watson and the Shark, for example, depicts the ocean as the mouth of Hell, a dark void filled with demons and tormented souls, while The Birth of Venus offers a more benign vision of the ocean as a life-giving force. In Children of the Sea, Daisuke Igarashi imagines the ocean as a giant portal between the terrestrial world and deep space, as is suggested by a refrain that echoes throughout volume one:

The ocean occupies a special place in the artistic imagination, inspiring a mixture of awe, terror, and fascination. Watson and the Shark, for example, depicts the ocean as the mouth of Hell, a dark void filled with demons and tormented souls, while The Birth of Venus offers a more benign vision of the ocean as a life-giving force. In Children of the Sea, Daisuke Igarashi imagines the ocean as a giant portal between the terrestrial world and deep space, as is suggested by a refrain that echoes throughout volume one:

From the back cover:

From the back cover: