If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.

In Saturn Apartments, the physical distance between us and our terrestrial home is small, but the emotional distance is great. The story takes place in a future where environmental devastation has prompted humans to decamp the Earth’s surface for its atmosphere, where they build an elaborate structure that encircles the planet. That floating city resembles Victorian London in its rigid class system and physical organization: the poorest people live in its bowels, in an artificially lit environment, while the richest live on the uppermost levels, enjoying natural light and unspoiled views of Earth.

Our guide to this stratified world is fourteen-year-old Mitsu, a professional window washer who lives on the lowest level. By virtue of his job, Mitsu has access to the entire city. For a boy who’s joined the workforce at an early age, who lives in a cramped room with few possessions, and whose neighbors suffer the ill effects of chronic light deprivation, his clients, most of whom live on the top floors, seem ridiculous and exacting. At the same time, however, they intrigue Mitsu; not only do they give him a glimpse into a more affluent way of life, they also own things — animals, machines, plants — that connect them to the Earth’s abandoned surface.

As these organisms and objects suggest, all of Saturn‘s characters suffer a strong sense of terrestrial homesickness. Midway through volume one, for example, Mitsu meets an eccentric zoologist who maintains an enormous private aquarium in his apartment. The man’s aquarium and his bizarre request that Mitsu splash water on the windows — something that’s impossible to do at an altitude of 35,000 kilometers — initially seem like a wealthy man’s whims; that is, until Mitsu learns that the zoologist is trying to create a more congenial environment for the aquarium’s prized specimen, the last surviving whale from a failed effort to reintroduce mammals into Earth’s oceans.

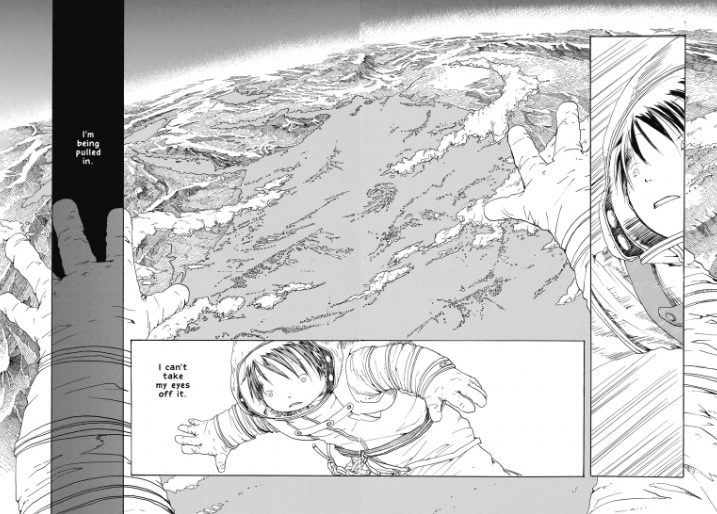

In other chapters, the characters’ longing to go home is more palpable. When Mitsu tackles his first assignment, for example, he finds himself at the very site where his father Akitoshi, also a window-washer, plunged to his death. Mitsu sees evidence of his father’s presence — a frayed rope, handprints on the side of the building — and though he interprets the evidence as proof of Akitoshi’s desperate struggle for survival, Mitsu is briefly seized by the thought that his father wanted to die, that Akitoshi cut the safety line so that he might fall back to Earth. Mitsu himself struggles with that same impulse; caught off guard by a strong solar wind, he finds himself dangling precariously above the Earth, mesmerized by the sight of the African continent spreading below him:

Only the intervention of Jin, an experienced co-worker, snaps Mitsu out of his dangerous reverie and spurs the boy to take corrective action. Once safely tethered to a lift, however, Mitsu peers over the side for another glimpse of the surface, resolving to one day “find the spot down there where Dad landed.”

Like Planetes, Saturn Apartments is less a tale of intergalactic derring-do than of ordinary people doing extraordinarily dangerous, tedious work in extreme environments. Most of what we learn about the characters comes from observing them on the job, as they banter with co-workers, perform routine tasks, and respond to crises. In Saturn Apartments, Akitoshi’s death — an event that took place five years before the story begins — casts a long shadow over the window washer’s guild. The mystery of what happened to Akitoshi plays an important role in advancing the plot, to be sure, but most of the story explores the way in which Mitsu comes to terms with his father’s death through learning Akitoshi’s profession and befriending Akitoshi’s colleagues.

The other thing that Saturn Apartments and Planetes have in common is beautiful, detailed artwork that conveys a strong sense of place. Hisae Iwaoka’s landscapes bustle with activity, showing us how the apartment dwellers go about their daily business. Each level has its own distinctive appearance, from the basement tenements — where Mitsu and Jin live — to the middle level — a tidy grid of schools and mid-rise buildings dotted with grassy parks — to the very top — a collection of spacious lofts with enormous windows. Iwaoka renders all of these environments in gently rounded, slightly imperfect lines that make the complex look warmly inviting, rather than sterile and prefabricated; even the very lowest levels of the complex are appealing, their close yet friendly quarters reminiscent of fin-de-siecle Delancey and Mulberry Streets.

Saturn Apartments is many things — a coming-of-age story, a set of character studies, a meditation on man’s place in the greater universe — but like all good space operas, its real purpose is to affirm the truth of T.S. Eliot’s words, “We shall not cease from exploration/And the end of all our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place for the first time.” Highly recommended.

Review copy provided by VIZ Media, LLC. Volume one of Saturn Apartments will be released on May 18, 2010. To read the first eight chapters online, visit the SigIKKI website.

SATURN APARTMENTS, VOL. 1 • BY HISAE IWAOKA • VIZ • 192 pp. • TEEN (13+)

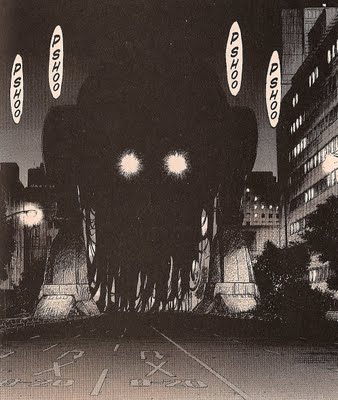

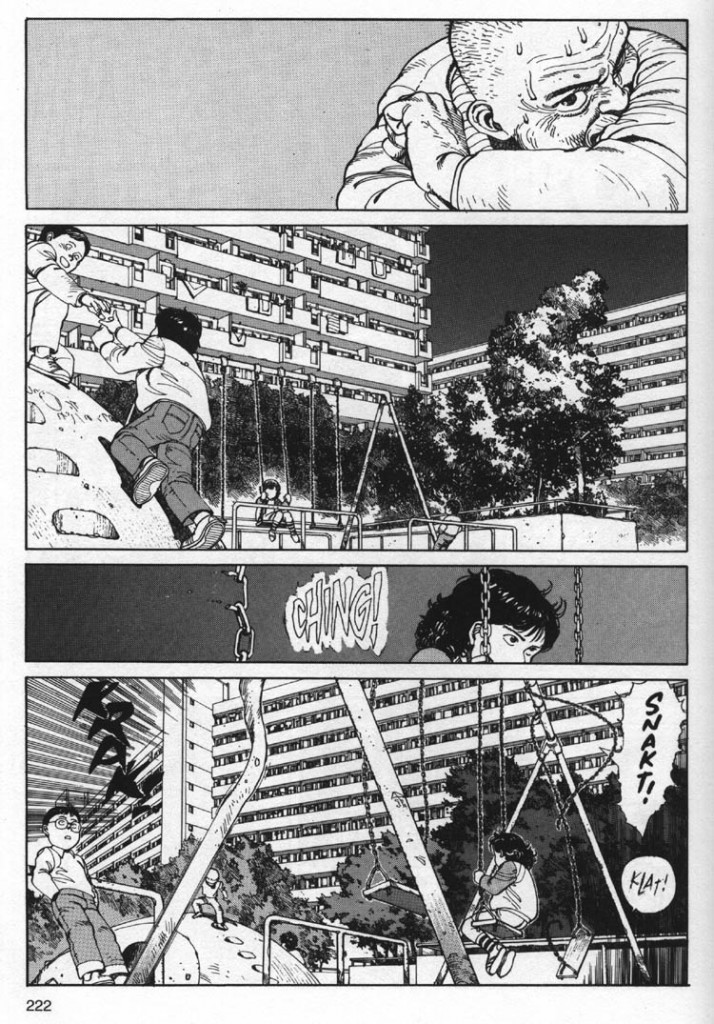

From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

Though the story is well-executed, the artwork is something of a disappointment. Itsuki goes to great pains to create a diverse cast — a task at which she’s generally successful — but her character designs are generic and dated; I’d be hard-pressed to distinguish the Kimaerans from, say, the cast of RG Veda or Basara. Itsuki also struggles with skin color; her dark-skinned women bear an unfortunate resemblance to kogals, thanks to Itsuki’s clumsy application of screentone.

Though the story is well-executed, the artwork is something of a disappointment. Itsuki goes to great pains to create a diverse cast — a task at which she’s generally successful — but her character designs are generic and dated; I’d be hard-pressed to distinguish the Kimaerans from, say, the cast of RG Veda or Basara. Itsuki also struggles with skin color; her dark-skinned women bear an unfortunate resemblance to kogals, thanks to Itsuki’s clumsy application of screentone.