Is it too soon to enjoy a pandemic-themed manga? That question was foremost in my mind as I read King of Eden, a new thriller that pits a group of globe-trotting scientists against an assortment of terrorist organizations that have weaponized a lethal virus. I’m happy to report that King of Eden didn’t remind me of the COVID crisis, but it did something arguably worse: it bored me.

The dullness of the story is all the more surprising for a series written by Takashi Nagasaki, Naoki Urasawa’s collaborator on such entertaining pot-boilers as Monster, Master Keaton, and 20th Century Boys. All of Nagasaki’s worst tendencies are on display in King of Eden: there are pointless flashbacks to the main characters’ childhoods, solemn monologues about the Old Testament, long-winded conversations about global terrorism, and an interminable lecture on the ancient Scythians that name-checks Herodotus because… why not? Though the first volume introduces a dizzying number of characters, Nagasaki barely fleshes them out. Even leads Rua Itsuki and Teze Yoo feel more like skill sets than actual people, as evidenced by an on-the-nose exchange in which a bureaucrat recites Dr. Itsuki’s resume and reminds her that she “hold[s] a black belt in Tae Kwon Do” and is “proficient in the Israeli martial art of Krav Maga” as if she didn’t know these things about herself.

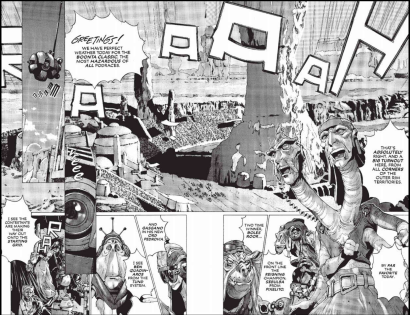

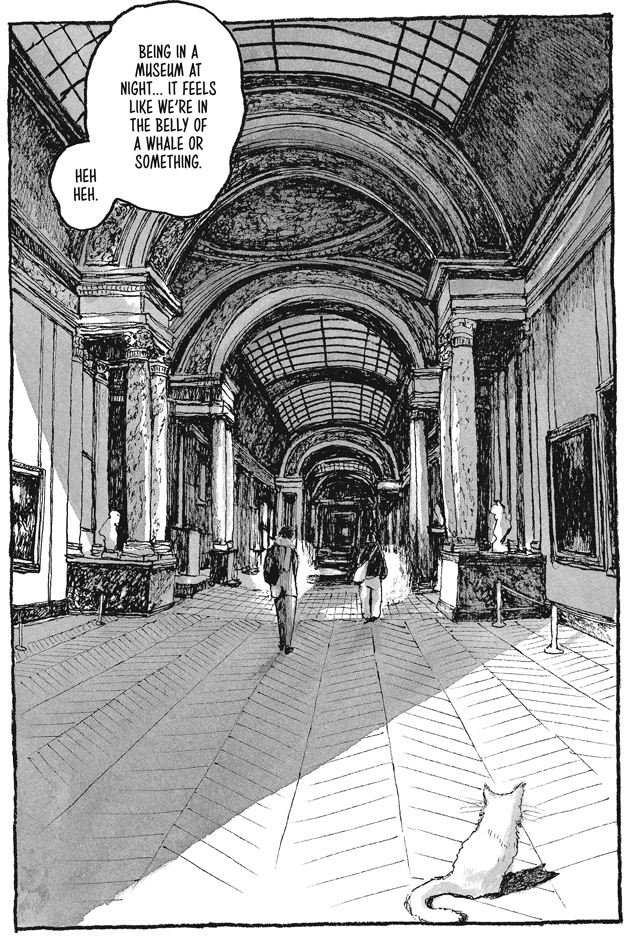

None of this would matter, of course, if King of Eden were entertaining, but Nagasaki is so intent on world-building that he overwhelms the reader with information, all delivered in such earnest, exhaustive detail it saps the narrative momentum. Itsuki and Yoo cross paths with MI-6 agents, WHO officials, IRA terrorists, crazy archaeologists, Interpol officers, and zombies—ZOMBIES, for Pete’s sake!—yet none of these encounters are memorable. Had Nagasaki placed more trust in artist SangCheol Lee (a.k.a. Ignito), King of Eden might have been a brisker, more imaginative entry in the zombie canon.

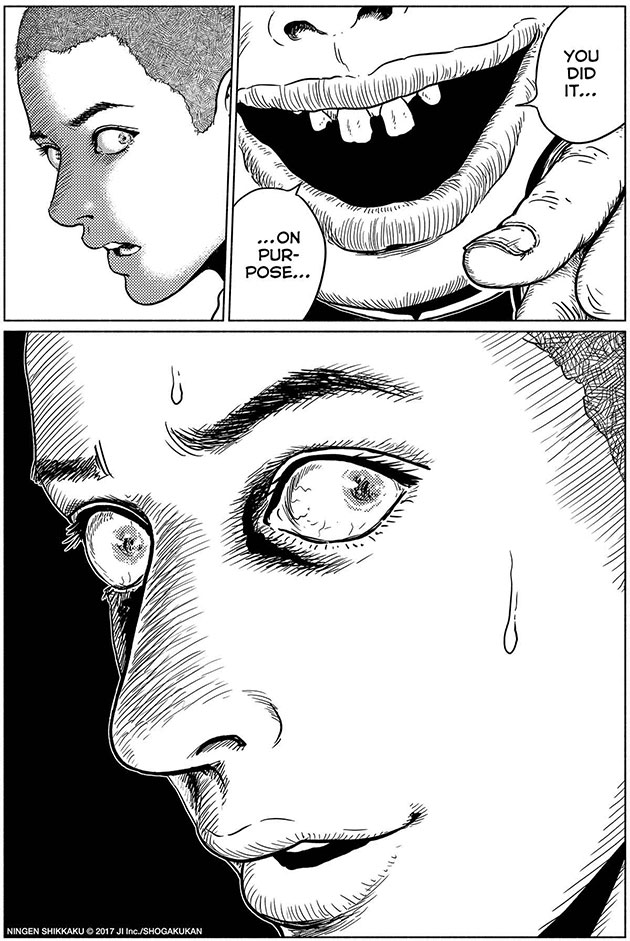

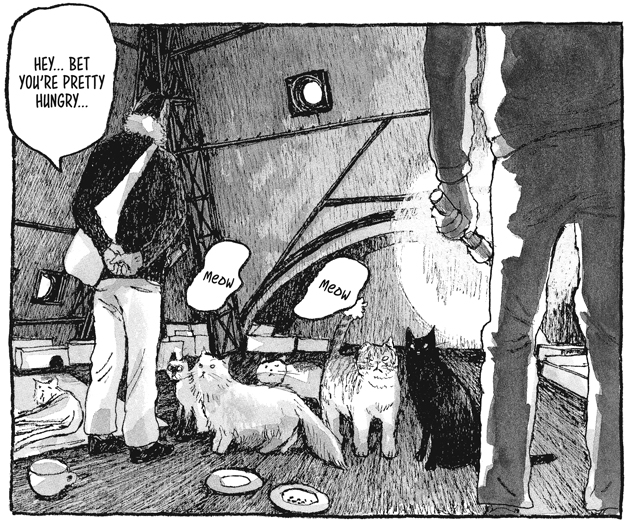

The first chapter offers a tantalizing glimpse of that potential partnership. Gone are the long-winded speeches; instead, Lee drops the reader into the action alongside two police officers who stumble across a baffling, gruesome scene. After the officers arrest a potential suspect, Lee skillfully cross-cuts between two spaces at the local precinct—an interrogation room and the morgue—allowing us to glimpse what’s unfolding in each room, and to feel the policemen’s growing unease. Lee’s crack pacing keeps the reader invested in the characters’ fate, building to a satisfying reveal of the carnage’s true source: a hideous, lantern-jawed creature that’s part werewolf, part zombie.

Alas, that cinematic flair disappears as soon as the characters begin talking; the next two chapters consist of information dumps punctuated by the occasional fist fight or car chase. By the time Nagasaki and Lee introduce a vampire arms dealer near the end of volume one, it barely registers as a major development. And that, in a nutshell, is what’s wrong with King of Eden: the story is so overstuffed with characters and events that I couldn’t muster the energy for another 15 or 100 chapters of talking heads explaining zombie behavior or Scythian culture just to figure out who this vampire is, and why he matters.

Yen Press provided a review copy of volume one.

KING OF EDEN, VOL. 1 • STORY BY TAKASHI NAGASAKI • ART BY IGNITO • TRANSLATED BY CALEB COOK • LETTERING BY ABIGAIL BLACKMAN • RATED OLDER TEEN (16+) • 384 pp.