If you’ve ever lived with a cat or dog, you know that no meal is complete without a pet hair garnish. Now imagine that your beloved companion actually prepared your meals instead of watching you eat them: what sort of unimaginable horrors might you encounter beyond the stray hair? That’s the starting point for Neko Ramen, a 4-koma manga about a cat whose big dream is to run a noodle shop, but author Kenji Sonishi quickly moves past hair balls and litter box jokes to mine a richer vein of humor, poking fun at his cat cook’s delusions of entrepreneurial grandeur.

Taisho is forever dreaming up ways to expand his business, ideas that seem sound in the abstract, but prove disastrous in the execution: a dessert ramen consisting of noodles and milk, a delivery service that’s thwarted by feline territoriality, a playing card promotion featuring unappetizing pictures of soup. In fact, Taisho is so completely misguided that he doesn’t grasp what’s novel about Neko Ramen; when a competitor in a cat costume opens a shop, hoping to capitalize on Taisho’s appearance on “The World’s Most Amazing Animals,” Taisho thinks he, too, needs an animal costume in order to drum up business. His sole customer, the long-suffering Tanaka-san, tries hard to offer sensible advice, but Tanaka’s counsel falls on deaf ears. (Why Tanaka sticks around for ramen that he freely admits is “awful” is one the series’ great mysteries.)

Sonishi’s artwork is crude and sketchy; each character is rendered with just enough lines to give a general impression of who or what he’s supposed to be. The primitive quality of the art actually works in the series’ favor, conveying the low-rent nature of Taisho’s business. More effective still is Sonishi’s strategy for differentiating Taisho from the other cats who regularly appear in the series: Taisho resembles a maneki neko (beckoning cat statue) in an apron, while other felines are depicted as simple, rounded shapes with ears and tails.

None of this would work if the translation were stiff or colorless, but TOKYOPOP wisely employed the husband-and-wife team of Emily Gordon and Kumail Nanjiani to adapt the script for English-speaking audiences. Both are experienced writers and performers (she wrote for Bust and Jane, he does stand-up comedy), and their ear for language is evident throughout volume one; the dialogue is idiomatic and the punchlines are snappy. The other secret to the script’s success is the care with which the adaptors distinguish Taisho’s voice from Tanaka’s, infusing the characters’ owner-customer banter the feeling of a good manzai routine, with Taisho as the boke and Tanaka as the tsukkomi.

The biggest surprise about Neko Ramen is that Sonishi manages to wring so many laughs out of what could be a one-joke premise. Sonishi’s gags remain fresh throughout the first volume, thanks, in part, to several interludes in which he abandons the 4-koma format to relate stories of Taisho’s past: his ill-fated stint as a cat model, his rivalry with a noodle shop staffed by a dog, a monkey, and a bird. These interludes nicely set the table for volume two, providing Sonishi more avenues for his absurd humor without straying too far from the series’ basic idea. Highly recommended, whether or not you fancy cats.

NEKO RAMEN, VOL. 1: HEY! ORDER UP! • BY KENJI SONISHI • TOKYOPOP • 156 pp. • RATING: TEEN (13+)

If I were thirteen years old, Library Wars would be at the top of my Best Manga Ever list, as it reads like a catalog of the things I dug in my early teens: books about the future, books about women breaking into male professions, books with bickering leads who harbor secret feelings for each other. I can’t say that Library Wars works as well for me as an adult, but I can recommend it to younger female manga fans who are tired of stories about wallflowers, doormats, or fifteen-year-old girls whose primary objective is to nab a husband.

If I were thirteen years old, Library Wars would be at the top of my Best Manga Ever list, as it reads like a catalog of the things I dug in my early teens: books about the future, books about women breaking into male professions, books with bickering leads who harbor secret feelings for each other. I can’t say that Library Wars works as well for me as an adult, but I can recommend it to younger female manga fans who are tired of stories about wallflowers, doormats, or fifteen-year-old girls whose primary objective is to nab a husband.

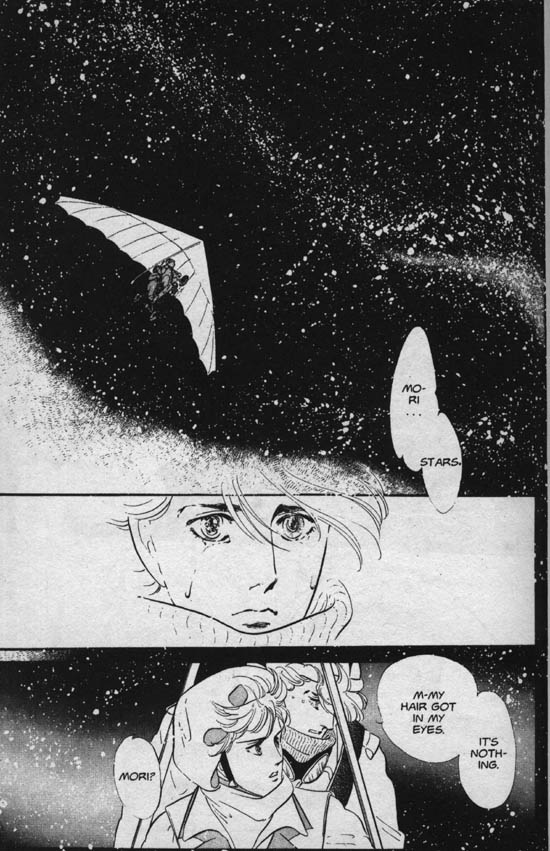

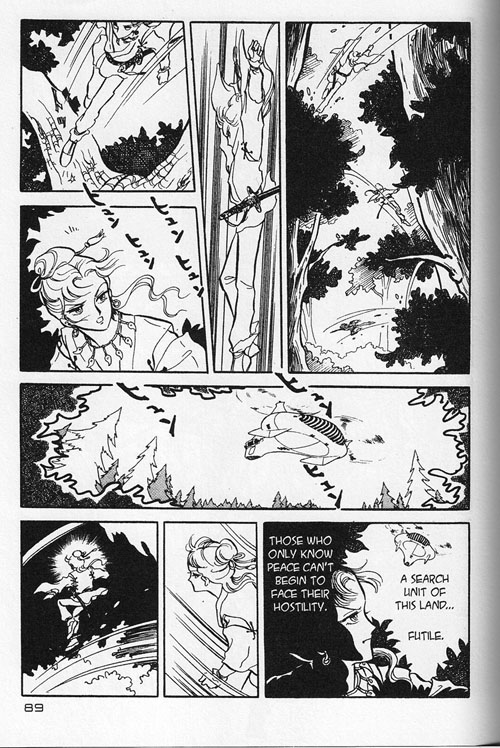

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

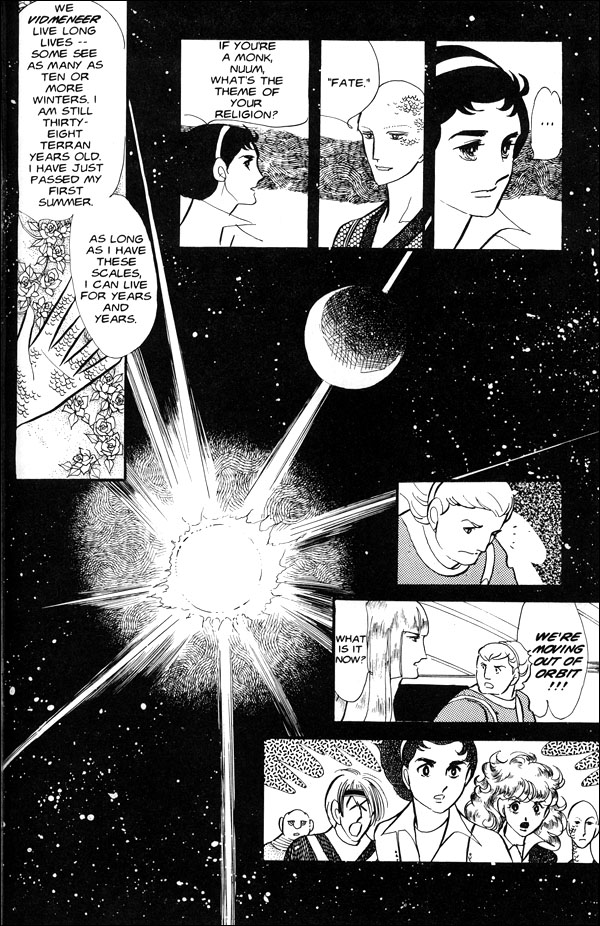

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

A, A’ [A, A Prime]

THEY WERE ELEVEN

THEY WERE ELEVEN

Ah, Keiko Takemiya, how I love your sci-fi extravaganzas! The psychic twins. The giant spiderbots. The evil, omniscient computers. The sand dragons. The fantastic hairdos. Just think how much more entertaining The Matrix might have been if you’d been at the helm instead of the dour, self-indulgent Wachowski Brothers! But wait… you did create your very own version of The Matrix: Andromeda Stories. Your version may not be as slickly presented as the Wachowski Brothers’, but you and collaborator Ryu Mitsuse engage the mind and heart with your tragic tale of doomed love, lost siblings, and machines so insidious that they’ll remake anything in their image—including the fish.

Ah, Keiko Takemiya, how I love your sci-fi extravaganzas! The psychic twins. The giant spiderbots. The evil, omniscient computers. The sand dragons. The fantastic hairdos. Just think how much more entertaining The Matrix might have been if you’d been at the helm instead of the dour, self-indulgent Wachowski Brothers! But wait… you did create your very own version of The Matrix: Andromeda Stories. Your version may not be as slickly presented as the Wachowski Brothers’, but you and collaborator Ryu Mitsuse engage the mind and heart with your tragic tale of doomed love, lost siblings, and machines so insidious that they’ll remake anything in their image—including the fish.

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society.

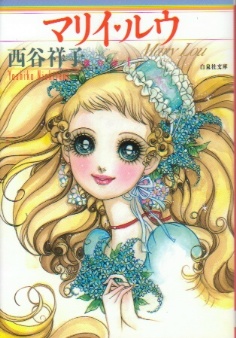

To Terra unfolds in a distant future characterized by environmental devastation. To salvage their dying planet, humans have evacuated Terra (Earth) and, with the aid of a supercomputer named Mother, formed a new government to restore Terra and its people to health. The most striking feature of this era of Superior Domination (S.D.) is the segregation of children from adults. Born in laboratories, raised by foster parents on Ataraxia, a planet far from Terra, children are groomed from infancy to become model citizens. At the age of 14, Mother subjects each child to a grueling battery of psychological tests euphemistically called Maturity Checks. Those who pass are sorted by intelligence, then dispatched to various corners of the galaxy for further training; those who fail are removed from society. In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in

In the mid-1960s, pioneering female artist Yoshiko Nishitani began writing stories aimed at a slightly older audience. Nishitani’s Mary Lou, which made its debut in Weekly Margaret in 1965, was one of the very first shojo manga to document the romantic longings of a teenage girl. (As Thorn notes in  The next time someone dismisses manga as a “style” characterized by youthful-looking, big-eyed characters with button noses, I’m going to hand them a copy of AX, a rude, gleeful, and sometimes disturbing rebuke to the homogenized artwork and storylines found in mainstream manga publications. No one will confuse AX for Young Jump or even Big Comic Spirits; the stories in AX run the gamut from the grotesquely detailed to the playfully abstract, often flaunting their ugliness with the cheerful insistence of a ten-year-old boy waving a dead animal at squeamish classmates. Nor will anyone confuse Yoshihiro Tatsumi or Einosuke’s outlook with the humanism of Osamu Tezuka or Keiji Nakazawa; the stories in AX revel in the darker side of human nature, the part of us that’s fascinated with pain, death, sex, and bodily functions.

The next time someone dismisses manga as a “style” characterized by youthful-looking, big-eyed characters with button noses, I’m going to hand them a copy of AX, a rude, gleeful, and sometimes disturbing rebuke to the homogenized artwork and storylines found in mainstream manga publications. No one will confuse AX for Young Jump or even Big Comic Spirits; the stories in AX run the gamut from the grotesquely detailed to the playfully abstract, often flaunting their ugliness with the cheerful insistence of a ten-year-old boy waving a dead animal at squeamish classmates. Nor will anyone confuse Yoshihiro Tatsumi or Einosuke’s outlook with the humanism of Osamu Tezuka or Keiji Nakazawa; the stories in AX revel in the darker side of human nature, the part of us that’s fascinated with pain, death, sex, and bodily functions. Reading The Times of Botchan reminded me of watching Alexander Sakurov’s cryptic 2002 film

Reading The Times of Botchan reminded me of watching Alexander Sakurov’s cryptic 2002 film  If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.

If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.