Move over, Chucky — there’s a new doll in town. His name is Hyde, and he’s a stuffed bear who wears a fedora, chomps cigars, and wields a chainsaw. (More on that in a minute.) Hyde belongs to thirteen-year-old Shunpei Closer, a timid junior high school student whose biggest talent is avoiding conflict. Watching Shunpei dodge bullies at school, it’s difficult to believe that he is, in fact, the grandson of Alysd Closer, a powerful, globe-trotting sorcerer with enemies on every continent. Keenly aware that his rivals might seek revenge against his family, Alysd created Hyde, a plush fighting machine capable of fending off attacks with a magical chainsaw. Hyde remained dormant for almost six years before the delivery of a mysterious package containing a murderous, knife-throwing sock monkey activated his abilities. (I can’t believe I just typed the phrase, “knife-throwing sock money,” but there it is.) Thus begins a kind of magical tournament manga that pits Hyde and Shunpei against an array of powerful sorcerers and their toy henchmen.

You don’t have to be a ten-year-old boy to find the sight of karate-chopping, knife-throwing dolls amusing, though it certainly helps. There’s a gleeful, go-for-broke quality to the fight scenes that evokes the feeling of real childhood play, a sensation akin to chopping off your Barbie’s hair or staging an epic battle between your sister’s My Little Ponies and your Star Wars action figures. Making these scenes even more enjoyable is Hyde, who sounds like an affectionate parody of James Cagney, punctuating the combat with sharp, funny one-liners that wouldn’t be out of place in The Public Enemy.

Yet for all the energy and goodwill engendered by these scenes, Hyde & Closer tends to bog down in exposition masquerading as dialogue, thanks to its rather complicated mythology. The rules of engagement are different for each opponent, which means that Hyde spends part of every fight outlining his strategy for defeating the villain du jour. Hyde isn’t the only character who sounds, at time, more like an omniscient narrator than a participant in the action; the villainous sock monkey, for example, lectures Shunpei at great length about Alysd’s true identity, scoffing at Shunpei for thinking gramps was an archaeologist. “That’s his cover story,” the monkey explains. “I guess no one told you anything.” (Or, more accurately, “I guess that’s my opening to disabuse you of that silly notion!”)

The battle scenes are further encumbered by Shunpei’s self-flagellating outbursts, usually along the lines of “I’m pathetic!” or “It’s all my fault!” Each time Shunpei doubts himself, the action comes to a screeching halt until he can muster the courage to stop whimpering and start fighting. Shunpei is clearly meant to be the kind of average-joe character that readers can identify with, but it’s hard to imagine anyone over the age of ten or eleven finding him sympathetic; after all, his bodyguard is quite handy with a chainsaw. Call me crazy, but I’d find that rather empowering.

If the script is a little creaky, Haro Aso’s artwork is bold, stylish, and suitably sinister. Hyde, by far, is his best creation, with his enormous button eyes, rakishly tilted hat, and jagged seams; he’s the perfect mixture of beloved stuffed animal and thirties gangster, easily transforming from a benign, wide-eyed toy to a glowering menace. (In a nice touch, the stitches on Hyde’s mouth are stretched to their limit whenever he’s spitting dialogue or downing one of his signature drinks: honey on the rocks.) The villains, too, are imaginatively rendered, from the jack-in-the-box with shark-like teeth to the kokeshi with lethal, snaking hair. (Hommage to Junji Ito, perhaps?) The only downside to Aso’s art is his penchant for extreme camera angles. He draws his fight scenes from so many different perspectives — from the floor up, the ceiling down, or directly behind Hyde’s head — that it’s hard to track the characters’ movement through the picture plane; characters have a tendency to pop up in unexpected (and sometimes illogical) places.

Still, it’s hard to deny the appeal of stuffed animal cage matches or teddy bears who swagger like James Cagney, and for those two reasons, I’m going to stick with Hyde & Closer to see where Aso goes with his Fight Club-meets-Winnie the Pooh premise.

HYDE & CLOSER, VOL. 1 • BY HARO ASO • VIZ • 200 pp. • RATING: OLDER TEEN (16+)

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal. The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal.

The emotional core of A Drunken Dream — for me, at least — is Hagio’s 1991 story “Iguana Girl.” Rika, the heroine, is a truly grotesque figure — not in the everyday sense of being ugly or unpleasant, but in the Romantic sense, as a person whose bizarre affliction arouses empathy in readers. Born to a woman who appears human but is, in fact, an enchanted lizard, Rika is immediately rejected by her mother, who sees only a repulsive likeness of herself. Yuriko’s disgust for her daughter manifests itself in myriad ways: withering put-downs, slaps and shouts, blatant displays of favoritism for Rika’s younger sister Mami. As Rika matures, Hagio gives us tantalizing glimpses of Rika not as an iguana, but as the rest of the world sees her: a lovely but reserved young woman. As with “The Child Who Comes Home,” the heroine’s appearance could be interpreted literally, as evidence of magical realism, or figuratively, as a metaphor for the way in which children mirror their parents’ own flaws and disappointments; either way, Rika’s quest to heal her childhood wounds is easily one of the most moving stories I’ve read in comic form, a testament to Hagio’s ability to make Rika’s fraught relationship with her mother seem both terribly specific and utterly universal. When I was fifteen and in the throes of my mope-rock obsession, I fantasized a lot about England, home to my favorite bands. I imagined London, in particular, to be a place where everyone appreciated the sartorial genius of Mary Quant, fashionable ladies accessorized every outfit with a pair of shit kickers, regular moviegoers recognized Eat the Rich as brilliant satire, and — most important of all — teenage boys appreciated girls with dry, sarcastic wits and gloomy taste in music. You can guess my disappointment when I finally visited England for the first time; not only was London dirty, expensive, and filled with tweedy-looking people who found my taste in clothing odd, many of the teenagers I met were fascinated by American pop culture, pumping me and my companions for information about — quelle horror! — LL Cool J. I could have died. Though I’ve gone through similar phases since then — Russophilia, Woody Allenomania — I’ve never been able to abandon myself to those passions in quite the same way, knowing somewhere in the back of my mind that all Muscovites weren’t soulful admirers of Shostakovich and that most book editors didn’t live in pre-war sixes on the Upper East Side.

When I was fifteen and in the throes of my mope-rock obsession, I fantasized a lot about England, home to my favorite bands. I imagined London, in particular, to be a place where everyone appreciated the sartorial genius of Mary Quant, fashionable ladies accessorized every outfit with a pair of shit kickers, regular moviegoers recognized Eat the Rich as brilliant satire, and — most important of all — teenage boys appreciated girls with dry, sarcastic wits and gloomy taste in music. You can guess my disappointment when I finally visited England for the first time; not only was London dirty, expensive, and filled with tweedy-looking people who found my taste in clothing odd, many of the teenagers I met were fascinated by American pop culture, pumping me and my companions for information about — quelle horror! — LL Cool J. I could have died. Though I’ve gone through similar phases since then — Russophilia, Woody Allenomania — I’ve never been able to abandon myself to those passions in quite the same way, knowing somewhere in the back of my mind that all Muscovites weren’t soulful admirers of Shostakovich and that most book editors didn’t live in pre-war sixes on the Upper East Side. Given the sheer number of nineteenth-century Brit-lit tropes that appear in The Name of the Flower — neglected gardens, orphans struck dumb by tragedy, brooding male guardians — one might reasonably conclude that Ken Saito was paying homage to Charlotte Brontë and Frances Hodgson Burnett with her story about a fragile young woman who falls in love with an older novelist. And while that manga would undoubtedly be awesome — think of the costumes! — The Name of the Flower is, in fact, far more nuanced and restrained than its surface details might suggest.

Given the sheer number of nineteenth-century Brit-lit tropes that appear in The Name of the Flower — neglected gardens, orphans struck dumb by tragedy, brooding male guardians — one might reasonably conclude that Ken Saito was paying homage to Charlotte Brontë and Frances Hodgson Burnett with her story about a fragile young woman who falls in love with an older novelist. And while that manga would undoubtedly be awesome — think of the costumes! — The Name of the Flower is, in fact, far more nuanced and restrained than its surface details might suggest. 5. Phoenix: Early Years, Vol. 12

5. Phoenix: Early Years, Vol. 12 4. X-Day

4. X-Day 3. A.I. Revolution

3. A.I. Revolution 2. GALS!

2. GALS! 1. Love Song

1. Love Song Duck Prince

Duck Prince Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales

5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS

5. PHOENIX, VOL. 12: EARLY WORKS 4. X-DAY

4. X-DAY 3. A.I. REVOLUTION

3. A.I. REVOLUTION 2. GALS!

2. GALS! 1. LOVE SONG

1. LOVE SONG DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended)

DUCK PRINCE (Ai Morinaga • CMP • 3 volumes, suspended) SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

SHIRAHIME-SYO: SNOW GODDESS TALES (CLAMP • Tokyopop • 1 volume)

Anthologies serve a variety of purposes. They provide established artists an outlet for experimenting with new genres and subjects; they introduce readers to seminal creators with a representative sample of work; and they offer a window into an early phase of a manga-ka’s development, as he or she made the transition from short, self-contained works to long-form dramas. Himeyuka & Rozione’s Story serves all three purposes, collecting four shojo stories by prolific and versatile writer Sumomo Yumeka, best known here in the US for The Day I Became A Butterfly and Same Cell Organism. (N.B. “Sumomo Yumeka” is a pen name, as is “Mizu Sahara,” the pseudonym under which she published Voices of a Distant Star and the ongoing seinen drama My Girl.)

Anthologies serve a variety of purposes. They provide established artists an outlet for experimenting with new genres and subjects; they introduce readers to seminal creators with a representative sample of work; and they offer a window into an early phase of a manga-ka’s development, as he or she made the transition from short, self-contained works to long-form dramas. Himeyuka & Rozione’s Story serves all three purposes, collecting four shojo stories by prolific and versatile writer Sumomo Yumeka, best known here in the US for The Day I Became A Butterfly and Same Cell Organism. (N.B. “Sumomo Yumeka” is a pen name, as is “Mizu Sahara,” the pseudonym under which she published Voices of a Distant Star and the ongoing seinen drama My Girl.) In Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics, author Paul Gravett argues that female mangaka from Riyoko Ikeda to CLAMP have often used “the fluidity of gender boundaries and forbidden love” to “address issues of deep importance to their readers.” Taeko Watanabe is no exception to the rule, employing cross-dressing and shonen-ai elements to tell a story depicting the “pressures and pleasures of individuals living life in their own way and, for better or worse, not always as society expects.”

In Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics, author Paul Gravett argues that female mangaka from Riyoko Ikeda to CLAMP have often used “the fluidity of gender boundaries and forbidden love” to “address issues of deep importance to their readers.” Taeko Watanabe is no exception to the rule, employing cross-dressing and shonen-ai elements to tell a story depicting the “pressures and pleasures of individuals living life in their own way and, for better or worse, not always as society expects.” THE FOUR IMMIGRANTS MANGA: A JAPANESE EXPERIENCE IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1904 – 1924

THE FOUR IMMIGRANTS MANGA: A JAPANESE EXPERIENCE IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1904 – 1924 The Four Immigrants Manga

The Four Immigrants Manga Parasyte

Parasyte Satsuma Gishiden

Satsuma Gishiden Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms

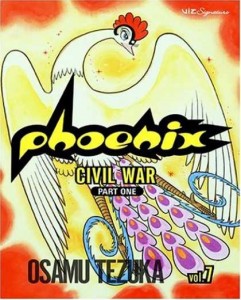

Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War

BONUS PICK: Phoenix: Civil War About two years ago, I reached a tipping point in my manga consumption: I’d read enough just enough stories about teen mediums, masterless samurai, yakuza hit men, pirates, ninjas, robots, and magical girls to feel like I’d exhausted just about everything worth reading in English. Then I bought the first volume of Taiyo Matsumoto’s No. 5. A sci-fi tale rendered in a stark, primitivist style, Matsumoto’s artwork reminded me of Paul Gauguin’s with its mixture of fine, naturalistic observation and abstraction. I couldn’t tell you what the series was about (and after reading the second volume, still can’t), but Matsumoto’s precise yet energetic line work and wild, imaginative landscapes filled with me the same giddy excitement I felt when I first discovered the art of Rumiko Takahashi, CLAMP, and Goseki Kojima.

About two years ago, I reached a tipping point in my manga consumption: I’d read enough just enough stories about teen mediums, masterless samurai, yakuza hit men, pirates, ninjas, robots, and magical girls to feel like I’d exhausted just about everything worth reading in English. Then I bought the first volume of Taiyo Matsumoto’s No. 5. A sci-fi tale rendered in a stark, primitivist style, Matsumoto’s artwork reminded me of Paul Gauguin’s with its mixture of fine, naturalistic observation and abstraction. I couldn’t tell you what the series was about (and after reading the second volume, still can’t), but Matsumoto’s precise yet energetic line work and wild, imaginative landscapes filled with me the same giddy excitement I felt when I first discovered the art of Rumiko Takahashi, CLAMP, and Goseki Kojima. PINEAPPLE ARMY

PINEAPPLE ARMY