|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MJ: “There is this fish.”

That’s the sentence that first comes to mind when trying to describe Reiko Shimzu’s Moon Child, the subject of this week’s Off the Shelf. I hear it in my head, a la the Boy from Jones & Schmidt’s The Fantasticks. “There is this fish.”

Let me see if I can do a little better. I first became acquainted with Moon Child by way of Shaenon Garrity’s Overlooked Manga Festival, which she begins with the sentence, “How insane does a manga have to be in order to be the insanest manga I’ve ever read?” She goes on to describe Moon Child, and I don’t know whether it was simply due to her delightful writing style or the truly bizarre train of thought behind Moon Child itself, but it was an article that seared itself into my brain forever. I’ve probably shared that link with more people since the first time I read it than anything else I’ve found on the internet, and that’s saying quite a lot.

Eventually, curiosity got the best of me, and I started collecting the series—if only to confirm that what Shaenon had presented to me could really, honestly exist. Result? It does, exactly as she describes it, and though it’s probably one of the most problematic manga I’ve ever read (on quite a number of levels), it’s also one of the most beautiful and one of the most intriguing.

MICHELLE: I am not exactly sure how I started collecting Moon Child. It was probably something along the lines of, “Ooh, look, here’s some more shoujo from CMX. Shoujo from CMX can’t be bad!” I bought the volumes religiously and have actually owned the whole series for a while without ever reading it… until this past week. And yes, indeed, it is quite insane!

MJ: So in the interest of helping our readers better understand all these cries of “Insanity! Insanity!” let me see if I can describe the basics of Moon Child‘s plot.

There is this fish.

No, sorry, I promised better. Okay. So. Art Gile is a former ballet prodigy whose career was abruptly stalled in his youth, thanks mainly to his inability to deal with the success of his partner, Holly, whom he’d helped along on the road to stardom. Now Art is a failed Broadway dancer with anger management issues and a tendency towards domestic violence. Driving back to his apartment after a bad audition, Art strikes a young boy with his car, sending both of them to the hospital. Though the boy appears physically uninjured, he seems to have lost his memory. Feeling responsible for the boy’s condition, Art unofficially adopts him, naming him “Jimmy.”

As it turns out, “Jimmy” is actually an alien mermaid named Benjamin, still in a sort of genderless larval form. Though, by day, he looks like a pre-adolescent boy in a suit and bow tie, moonlight transforms him into a beautiful (female) mermaid with long, flowing hair and soulful eyes and the inability to speak when it counts. We soon learn that these mermaids, scattered all across the universe, return to earth every six hundred years or so to spawn a new generation. We also learn that Jimmy/Benjamin is a descendant of the actual “Little Mermaid,” and that her entire clan is dedicated to making sure that Benjamin, unlike her mother, will appropriately mate with a merman instead of falling for a human, thereby thwarting a prophesied environmental catastrophe certain to wipe out their entire population.

Complicating matters further, Benjamin is left to the care of her two siblings, Teruto and Seth, who have long been instructed that their purpose in life is to see that Benjamin matures into an egg-bearing female and mates properly, at which point they will merely dissolve into foam.

Seeing that Benjamin may potentially defy her duty by falling for the human, Art, her siblings battle (not quite successfully) the desire to remove her from the picture so that one of them can properly take her place.

MICHELLE: But the siblings are unable to actually do anything to Benjamin themselves, so Teruto, the more active of the pair, strikes a deal with the same witch who brokered his mother’s bargain to become human, and ends up possessing Gil Owen, the heir to an influential investment group, which results in the story being all about Chernobyl and Gil’s exceedingly convoluted plans (I am not even sure about this) to get Art to come to Kiev and then drive him so insane with the belief that Benjamin will destroy the world that he kills her. From a story that starts off about mermaids it really is entirely, as Shaenen Garrity wrote, all about water pollution.

MJ: Though there are numerous details we’ve declined to mention so far, as you can see, the series’ plot is fairly… esoteric. Furthermore, as I mentioned in the beginning, the series is problematic on a number of levels, including the visual age gap between “Jimmy”‘s usual form and that of his romantic prospects (Art, of course, and a merman named Shonach who is captivated by Benjamin’s beauty), his cheerful acceptance of Art’s physical abuse, and the highly unfortunate depiction of the mer-people’s prophet, Grandma, as a cross between a minstrel show caricature and a woman from the Burmese Kayan Lahwi tribe. (Click if you really want to know.)

But amidst all the crazy plotting, questionable characterization, and possible racism, there is a poignance and a unique beauty to this manga that is difficult to fully convey, though we’ll certainly do our best. And I hate to jump right to the ending, but I’ll admit that the series’ final volume—which provides two different possible endings, without making it fully clear which one is real—pretty much redeemed all its faults for me in one go. How often does that happen?

MICHELLE: The ending is very interesting, indeed! I will say, though, that leading up to it is a lot of stuff that doesn’t make a lot of sense, and for me, once you’ve reached the critical mass for “wtf” it spills over into “whatever,” so there were certain aspects of the conclusion that didn’t affect me as much as they might’ve, though there were a few subplots I liked very much.

MJ: I have a feeling there will end up being a bit of a divide here between us at some points—not because I think things necessarily made sense, but because that doesn’t matter nearly as much to me as it does to you. But I expect the conversation will be lively! So, why don’t we start off with some of the things we most liked, and then move on to the rest later? Where would you like to begin?

MICHELLE: With the twins. Really, I thought they were the most interesting aspect of the story, much more so than crybaby Benjamin who beguiles men purely on the basis of being lovely. I sympathized a lot with Teruto, who was bitter at having sullied his soul to provide for his gentler siblings and was to be rewarded for all that he had done with dissolving into foam. I also really enjoyed Seth’s journey, as after Teruto embarks on his plot for revenge he is given a chance to spread his wings and become more independent. I rooted for his relationship with Shonach from the start and enjoyed just about everything involving them up until the final volume. I didn’t care about Jimmy/Benjamin and her love for Art nearly as much.

MJ: I think I’m sort of half with you and half not. I absolutely agree with you about how fascinating the twins are, and I love the fact that though Teruto is, ultimately, the villain of the story, he’s also one of the most relatable characters by far. It’s pretty much impossible not to understand his resentment over his fate, which seems tragically unjust, and his devotion to Seth is quite moving. Seth’s journey, as you say, is also one of the most interesting aspects of the series, and he ends up being the character we care most about in the end.

On the other hand, I’m not quite with you on either the Seth/Shonach relationship or your feelings about Benjamin/Jimmy. I have to admit that I kind of hate Shonach. Probably he doesn’t deserve it—I realize that—but it really bothers me that his obsession with Benjamin’s beauty (her beauty only—he doesn’t care about her as a person at all, really) keeps him from being able to appreciate the best parts of Seth, to the point that even at the end, when Seth has matured into a female, he can only see her as Benjamin. That the only expression of true affection Seth ever really gets from Shonach is when he believes she is Benjamin really breaks my heart.

Also, I admit I really do care about Jimmy/Benjamin, and I see her as being wronged pretty much throughout the story. She’s not responsible for her pre-destined role as this super-important mermaid who holds the fate of her race in her hands any more than Teruto or Seth are responsible for their pre-determined futures as bubbles of foam. Benjamin doesn’t want to mesmerize men with her beauty. If anything, she wants to be able to live indefinitely as Jimmy, so that she can preserve the relationship she (inexplicably) treasures with Art. But with everyone tugging at her fate from every side, what she’s got is a lot of unwanted attention from Shonach (for all the wrong reasons), a deteriorating relationship with Art (who is incapable of accepting her as an adult woman), and everyone and their mom out to kill or ruin her in one way or another. If I were Benjamin, I’d cry too!

MICHELLE: You know, it never occurred to me that Shonach was to blame for his fixation on Benjamin, but you’re absolutely right in terms of the limits of his feelings and how that blinded him to Seth most of the time. And yeah, I know that Benjamin doesn’t mean to mesmerize men, but… maybe Teruto’s plight just resonated with me extra strongly for various personal reasons, and so I came to regard her much like he does. I certainly didn’t feel this way about her in the beginning!

Also, I think I could’ve liked Benjamin more if I had really seen what she saw in Art, but because I couldn’t it affected the way I perceived her feelings for him. Of course, one can have genuine feelings for shitty people, but I got so irked at various times that my capacity for being thoughtful was impacted. It didn’t help that she—incapable, as Teruto pointed out, of doing anything for herself—eventually seemed to be trying to ruin Art so that he would kill her.

MJ: I can definitely agree that it’s really difficult to understand what Benjamin sees in Art. For my own various personal reasons (heh) I can understand her desire to help him rise up out of his professional slump so that he can regain his self-esteem, and he also proves his devotion to her in many ways throughout the course of the series, and I can see why she’d desire that, especially from someone outside the mer-world where she’s valued only as a sort of angel/demon icon. But it’s so difficult for me to swallow his abusive tendencies, that my view of him is ultimately pretty negative.

On a different note, one of the characters I ended up liking most by the end was Holly, who I’d hated early on for her manipulation of Art and her cruelty towards Jimmy. I was actually pretty surprised that I could end up liking her as much as I did, given where we started. But by the end, she was one of the few likable characters left.

MICHELLE: Speaking of Art’s profession, I did wonder whether the parts where we actually see him performing were among your favorites!

I never entirely warmed to Holly, but it did seem that concern over her brother’s fate—he’s in Colombia when an earthquake strikes—tempered her bitchy tendencies in a major way, and she was actually pretty horrified by what Gil was attempting to do, and much more attuned to there being something really wrong than Art, who was basically like, “I’m responsible for my sponsor’s injury so I will do whatever he says, especially if that happens to be touring a nuclear facility.”

Another unexpectedly fun character is Gil’s personal secretary, Rita. I admit, she’s quite a favorite for me. Tall, large, and unlovely, Rita harbors a crush on Gil even before Teruto takes possession of his (secretly terminally ill) body. When Teruto realizes her psychic gifts can amplify his own powers, he makes her his right-hand woman, and quells her questions with sex. I was disappointed that she turned out to be crazy, but her bizarre actions did help ratchet up the tension.

MJ: I loved Rita! I hate that she’s easily manipulated by her interest in Gil, but I can understand it, and really it only made me feel more indignant on her behalf. I suppose I, too, was disappointed that she turned out to be crazy in the end, but she wasn’t any crazier than Teruto/Gil by that point, so I was still rooting for her on some level. I kept sort of hoping she would ultimately prevail, but I’m not even sure what that would have meant. I am sad that she never got to see how her crush on the real Gil might have played out. I suppose she would have had little chance (even if he wasn’t dying) but I really hated the way she was treated by Gil’s overprotective sister, and I would have loved for the sister to have been proven wrong for real. You know. Not just because her brother’s body got taken over by the soul of a vengeful alien mermaid.

And to answer your earlier question, yes I really did love the parts where we saw Art actually performing! I loved all the ballet stuff, actually, including the bits with Artem Zaikov, the Russian dancer who (for his own personal reasons—I guess we shouldn’t spoil everything) has it in for Art, but who ultimately won my heart by way of his charming family.

MICHELLE: Characters who look like Rita are so rare in manga that I think it’s utterly natural to root for them and hope they will prevail. Which… I suppose in a way she did, but not in a way that made her feel any better about herself.

And I was just going to ask you about Artem! When Gil was first introduced, I thought, “Wait, who is this guy?” It soon became clear what his story was, however. Shimizu duplicates this feat near the end, with Artem’s introduction providing another “Wait, who is this guy?” moment that eventually proves pivotal to the climax of the series. I really liked him, and was especially impressed by the way his dancing was drawn—I swear, Shimizu was able to perfectly capture the ways in which his style differs from Art’s.

MJ: Yes, she really does! I feel pretty strongly that Shimizu must be a real ballet fan. Okay, I’m going to end up spoiling things after all, here, but it seems likely to me that she based Art and Artem’s mutual father, “Rimsky” on the legendary Russian dancer Vaslav Nijinsky (despite entirely glossing over his sexuality), right down to the mental illness that ultimately ended his career, and she passed down some of his defining characteristics to Artem.

Among other things, Nijinsky was known for his sensuality and androgynous appearance onstage, which is exactly how she characterizes Artem. There’s a little Nureyev in there, too (which is more appropriate to the time period), but I feel like her real interest is Nijinsky. And despite Artem’s claim that it’s Art who is “the reincarnation of Rimsky,” it’s Artem who most resembles what we know of Nijinsky, body type notwithstanding (Nijinsky was kinda stocky).

MICHELLE: Check out MJwith the ballet knowledge!

I think Shimizu likes the idea of parental characteristics being split between siblings. Rimsky’s look and style are passed down to Artem, but his must-kill-love-interest-she-is-dangerous traits are passed to Art. Meanwhile, Seira’s love for the human prince is inherited by Benjamin, while her love for her original mer-person fiancé is embodied in Seth.

MJ: Oh, what a smart observation, Michelle! I hadn’t thought of that, but you’re absolutely right. With that in mind, it becomes even easier to understand Teruto’s tragedy. He’s the only one of Seira’s offspring to receive basically nothing from her. I think one of the most poignant moments in the series is the flashback in which Teruto overhears one of their caretakers talking about the fact that it’s really only Benjamin and Seth who are priorities, because Teruto is (essentially) barren. And since these mermaids seem to be valued only for their ability to bear eggs, they might as well be saying that Teruto has no soul. It’s that devastating.

MICHELLE: You can’t see me, but I am nodding emphatically. Teruto’s entire purpose is to protect the other two; he’s not destined to have any future of his own. Really, though, none of the mer-people are, as we learn late in the series (and I can’t tell if this was planned all along or what) that they will all die shortly after spawning. I feel like Shimizu could’ve emphasized the biological imperative a bit more—early on, there are many comparisons to fish, along with visuals of the spacefishies returning to Earth, but at the time we didn’t know that this would also be their final journey. Though, I guess if I were really up on my ichthyology, I might’ve expected it.

MJ: Mostly, I feel that revealing this late in the story was really effective. I thought it was kind of a brilliant way to suddenly change the reader’s perspective and it’s interesting, too, because it simultaneously makes things seem both more and less urgent, in terms of the relationship issues we’ve been following the entire way through. But since we’ve managed to stumble on one of the areas where you feel Shimizu fell down a little, let’s steer our way in that direction. I’m sure you’ve been bursting all along with the need to scream, “BUT IT DOESN’T MAKE SENSE!” Am I right?

MICHELLE: Not exactly bursting, and (perhaps surprisingly) not at all over the general concept itself. Once something crosses that surreal threshold, it becomes easier to accept whatever kooky setup the creator wishes to explore. But certain particulars of the plot did bug me, like “Why do these guys love Benjamin?” or, most significantly, “How does Teruto/Gil doing all this stuff accomplish his goal of having Seth turn into a female and bear eggs?”

MJ: Well, I think the first question we pretty much have to chalk up to Benjamin’s physical allure, which is made out to be pretty spectacular in a very specific, fantasy-driven way. Benjamin is drawn as a classic fairy-tale princess, all wide eyes and golden, billowing hair—a stark contrast to all the sleek, modern women in the series, like Holly. I think we’re supposed to pretty much take it as a given that all men are helpless in the face of that kind of beauty.

The only reaction that is a bit more complicated is Art’s, since he’s more attached to the (in his mind) sexually null Jimmy. By the way, am I the only one who noticed that Jimmy seems to get younger and younger as the series goes on? At first it really bothered me, but after a while I started to think that Benjamin might be achieving that by pure strength of will, in her ongoing effort to try as hard as possible to be what Art most wanted her to be— almost like some kind of automatic defense mechanism. Like a chameleon.

Regarding Teruto/Gil… well, I think it becomes pretty clear after a while that Teruto is much more driven by his need to destroy Benjamin than he is by his desire to put Seth in her place. I mean, the idea is supposed to be that if Benjamin dies, Seth will be the next in line to mature into a female. But it certainly seems like this could have been accomplished much more easily by other means. Somehow.

MICHELLE: Yeah, I don’t think Chernobyl needed to blow up in order for Benjamin to die. A suggestion to Rita would’ve done the trick, I’m sure.

I’m glad you mentioned that about Jimmy, because I definitely noticed it, too! There’s one scene in volume three (pages 86-87) where her size is extremely variable. Sometimes he looks more five than twelve! I wondered if it was intentional on Jimmy’s part, but Art doesn’t react at all, so I suspect it’s a Shimizu issue.

MJ: And when we first see Jimmy, she looks pretty much exactly the same as Teruto and Seth do later on, which is to say maybe mid-to-late teens. Originally, I thought maybe Shimizu changed her mind about Jimmy’s visual age to avoid dealing with any issues regarding Jimmy’s sexuality except when she appears as Benjamin, and maybe to avoid Art having to be confronted by that as well. But I was never really sure.

MICHELLE: Yeah, me neither. Probably “never really sure” is just a state of mind one has to become accustomed to with Shimizu’s works.

Alas, no others have been licensed in English and aren’t likely to be now that CMX has disappeared. (Please bow your heads for a moment of silence.) I have thirteen volumes of Princesse Kaguya in French waiting to be read, though, and her josei series Top Secret is also coming out en Français.

MJ: I really would like the opportunity to read more of her work. As weird as Moon Child is, it feels really… I don’t know… organic. And I think Shimizu’s omake sections are actually really telling, here. I don’t always read these, but I poked through a few of hers, and my immediate impression was, “Oooooh, this is what it’s like in her mind all the time.”

MICHELLE: Yeah, those are really kooky! The two robot characters who feature in the omake, Jack and Elena, star in a string of stories by Shimizu, beginning with Milky Way, so they’d be familiar to her regular readers. It makes me wonder if, in some subsequent series, there might be similar omake starring the cast of Moon Child!

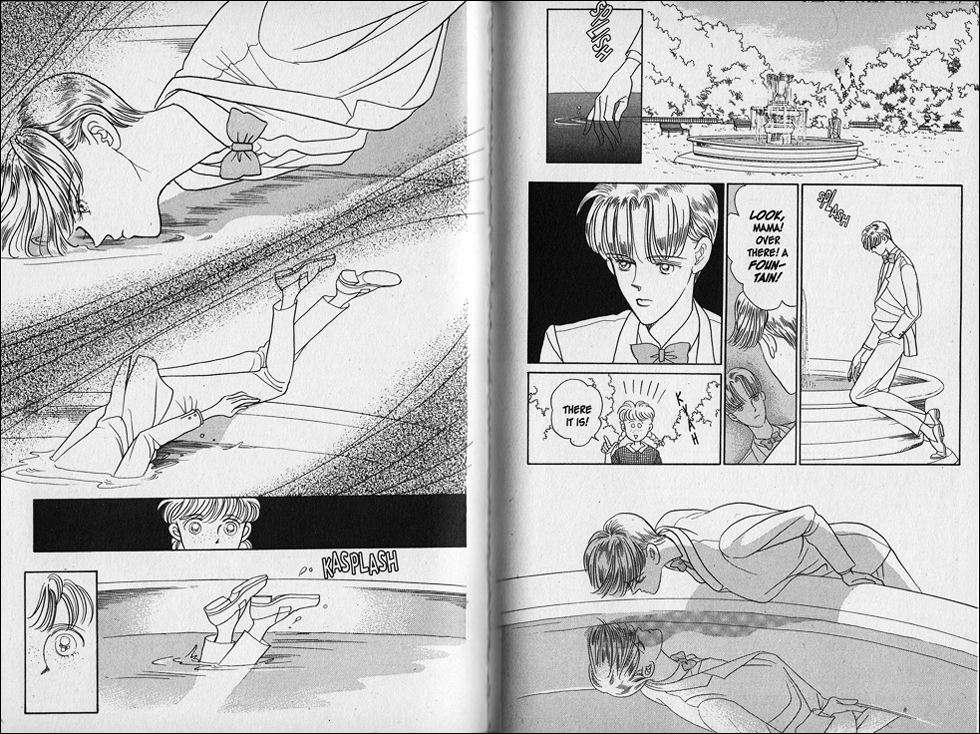

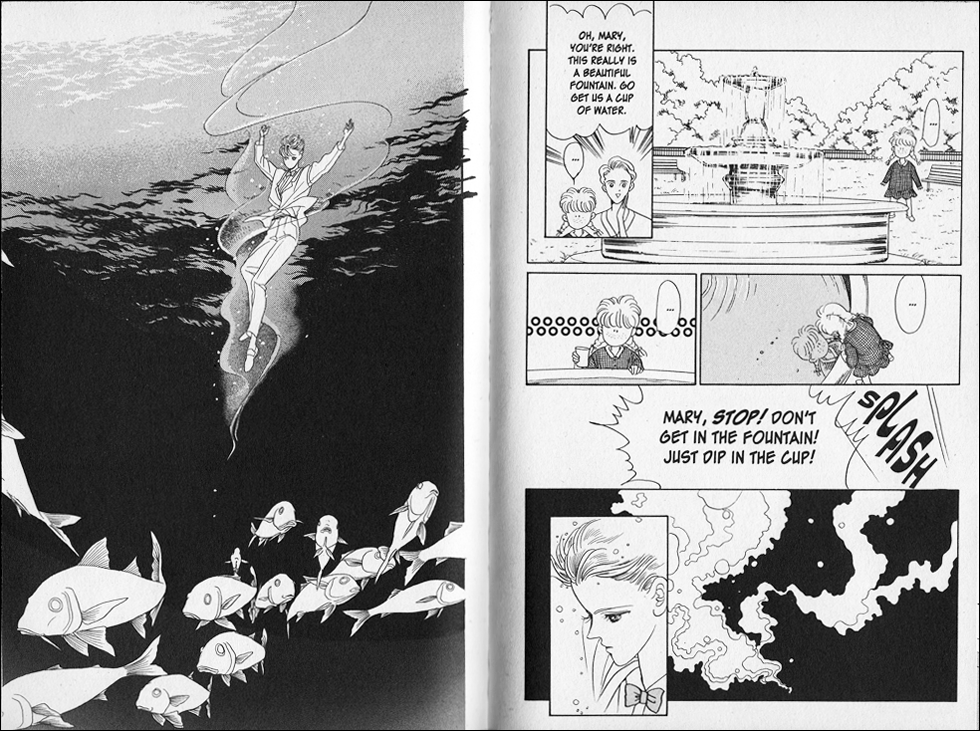

MJ: So, before we wrap up, I just want to gush a little bit about Shimizu’s artwork. You know I’m a huge fan of shoujo from this era, and really, there could be no better example of why that is. I chose a scene from this series back on our Let’s Get Visual column Celebrating the Pretty, and seriously that is still one of my favorite sequences of all time.

Yet, I’m leafing through the books now, and page after page, I’m seeing visuals that just pretty much blow me away with their haunting beauty, like the dream tidal wave in volume seven, or the creepy, creepy fish inquisition in volume eight. In many ways, it’s the series’ weirdness that makes it work so well for me, visually, because it’s so well-suited to Shimizu’s artistic mind.

MICHELLE: That wave! Here’s what I wrote about it in my notes: “A… very trippy sequence with a wave ensues.” There are many strange and lovely sequences in the book.. I was disappointed that we saw less and less of the fishy manifestations as the series went on, but I believe that’s tied in to Benjamin’s form stabilizing as she matured. I also really liked the exquisitely detailed line drawings that frequently appear in between chapters.

Another thing that impressed me was Seth’s female form, who was so very beautiful—more than Benjamin, even—and entirely feminine, and yet everything about her mannerisms still made it clear that she is Seth. She actually appears on the cover before she appears in the manga, and I blinked for a second in puzzlement and then got geekbumps when I figured out who it was.

MJ: Oh, you’re absolutely right! Honestly, I felt chills through the entire scene in which Seth finally transforms. Not only is she so completely, utterly Seth, but the way Shimizu reveals the transformation, in rapid, chaotic spurts, just as Seth must be experiencing it, is absolutely stunning.

MICHELLE: I just got geekbumps again thinking about it. Although I admit, I have to squash the logical part of my brain that’s demanding to know how she and Shonach did the deed when she was in her neither male nor female state.

MJ: I feel that adolescent mermaid sex is one of those things we’re just better off not really thinking about.

MICHELLE: I cannot help but concur.

MJ: You don’t know this yet, but I’ve been going pretty much crazy here with scanning in artwork. There’s just so much I want to share with our readers. I know that Moon Child is in many ways a great big mess, but honestly this is the kind of series I most long to see more of in English. It’s just so beautiful and so unique. There are a lot of current shoujo series that I love very much, but it’s this stuff that I really hunger for as a reader. It’s something I can’t get in any other medium. Not like this.

MICHELLE: I wish I could be hopeful that we’ll see more manga like this in the future, but taking chances in this business doesn’t seem to pay. Every series has its faults, and Moon Child is not an exception, but that doesn’t mean I’m not infinitely grateful to CMX for making it possible for us to read it.

MJ: I most certainly am. And yes, I know that historically these series have not been strong sellers. I guess all we can really do is to continue to write columns like this, in hopes of getting more readers interested in the kind of manga we wish we could see more of.

More full-series discussions with MJ & Michelle:

Princess Knight | Fruits Basket | Wild Adapter (with guest David Welsh)

Full-series multi-guest roundtables: Hikaru no Go | Banana Fish | Gerard & Jacques | Flower of Life

Fans of Kazuya Minekura’s unfinished BL action series

Fans of Kazuya Minekura’s unfinished BL action series