Most American manga fans know Katsuhiro Otomo as the creative force behind AKIRA and Domu: A Child’s Dream, but Otomo’s catalog also includes works like The Legend of Mother Sarah, in which Otomo penned the script but relinquished the illustration duties to another manga-ka. And while Mother Sarah isn’t quite as visually dazzling as AKIRA or Domu, this post-apocalyptic adventure is every bit as fun to read, thanks to its vivid characterizations and dynamic action sequences.

Set in the not-too-distant future, Mother Sarah begins in space — or, more accurately, space stations, where the survivors of a nuclear holocaust have sought refuge from the Earth’s extreme climate changes. When riots threaten the peace aboard these floating cities, the military evacuates civilians back to the surface, in the process separating thousands of children from their parents. Sarah, the story’s eponymous heroine, is on a quest to find her own family, all of whom disappeared in the chaos aboard the space stations. Traveling with Tsue, a trader, she wanders a desolate landscape of crumbling cities, slave-labor camps, religious compounds, and hardscrabble farms, karate-chopping anyone who threatens the honest folk she meets along the way.

Given its classic premise and cool, resourceful heroine, it’s curious that Mother Sarah had such a short shelf life here in the United States. As tempting as it may be to chalk up fan indifference to sexism, or antipathy towards Otomo’s other (read: not AKIRA) projects, I think the real reason lies with the way Mother Sarah was released. Dark Horse published the series from 1995-98, but only collected the first eight issues into a trade paperback. When read in thirty-page installments, The Legend of Mother Sarah: Tunnel Town is engaging but frustrating. Otomo and artist Takumi Nagayasu’s sense of pacing, in particular, is too leisurely for a stand-alone booklet: they establish a new setting with a dozen wordless panels, luxuriate in an explosion, or depict a fist-fight over five or six pages, gobbling up real estate that might otherwise be advancing the story. Contrast an issue of Tunnel Town with that of a long-running American series and the incompatibility of format and story becomes more apparent. In each issue of The Walking Dead, for example, one important event is dramatized: the characters make a critical discovery about their zombie foes or confront a troublemaker within their ranks. Though the issue may end on a cliffhanger, there’s a sense of closure that’s missing from an issue of Mother Sarah, even though both stories are clearly intended to extend beyond the confines of a single pamphlet.

When read in trade paperback form, however, Tunnel Town has a more satisfying rhythm. Those establishing shots and slow-mo fight scenes draw the reader deeper into the story; we feel like we’re actually part of the scene, rather than passive witnesses to the action. The continuity between events is easier to appreciate as well. Sarah’s skirmishes with authority no longer seem like a string of isolated incidents, but a steadily escalating pattern of violence that demands resolution. And what a finale! Coming at the end of two hundred pages, the denouement is less a cool stunt than a thrilling affirmation of Sarah’s courage and smarts, an emphatic punctuation mark at the end of a long but well-reasoned paragraph.

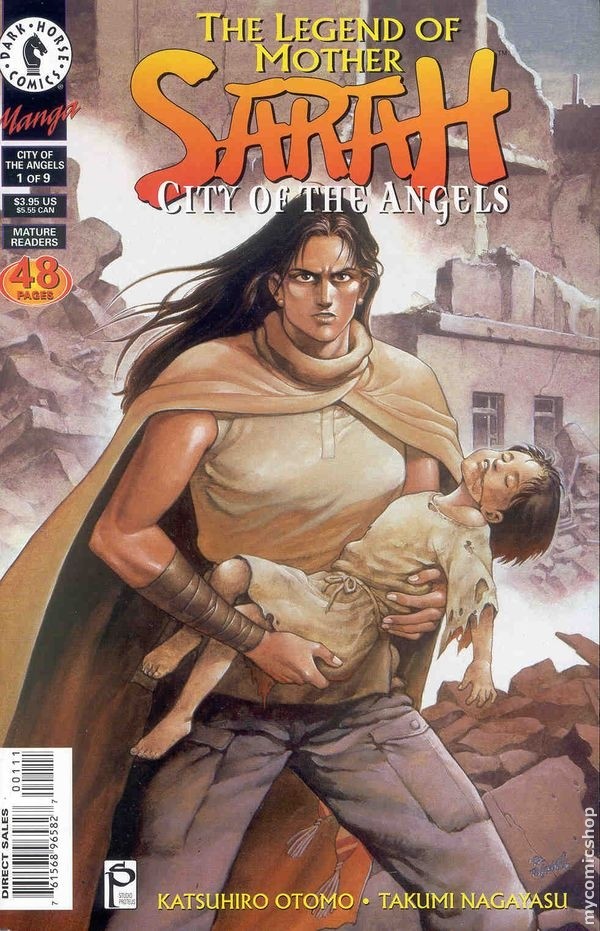

I’m guessing that someone at Dark Horse must have thought Mother Sarah was ill-served by the thirty-page format, as the next two arcs — City of the Children and City of the Angels — were published in forty-eight page installments, a development highlighted on the front covers of each issue:

As a result, the later mini-series are more engaging; we’re treated to a larger, more satisfying chunk of story in each installment, a chunk that I suspect corresponds more closely to the way the manga was serialized in Young Magazine. Alas, neither Children nor Angels were collected in bound form, making it harder for a new generation of manga fans to discover the series for themselves.

For all my grumbling about format and scarcity, however, all three story arcs are worth owning, both for the art and the story. Takumi Nagayasu’s crisp visuals are pleasingly reminiscent of Otomo’s. Nagayasu’s characters are drawn in a naturalistic fashion, with plenty of attention given to hands, facial hair, posture, wrinkles, and muscles; even the most inconsequential soldier or civilian is given a unique face and a thoughtfully constructed costume. Nagayasu also shares Otomo’s love of vehicles and decaying urban landscapes, rendering both in a fine, evocative fashion; one can almost hear the steel structures rusting from neglect.

Otomo’s writing is as strong as Nagayasu’s artwork. Though Sarah is a certifiable bad-ass, capable of kicking and stabbing her way out of a tight situation, she relies on her wits just as frequently as her fists. Her maternal instincts, too, inform much of her decision-making; throughout the series, Sarah is drawn to conflicts involving exploited or abused children, offering her a chance to symbolically “save” the family she lost ten years earlier. In short, Sarah is a woman warrior in the Lt. Ellen Ripley/Sarah Connor mold: fierce, strong, principled, and, above all else, a mama grizzly who sides with the young and the helpless. Oh, and she looks good while dispensing justice, too. Now that’s my kind of escapism, no matter how it’s packaged.

Cross Game, Omnibus Vol. 1 (Japanese vols. 1-3) | By Mitsuru Adachi | Viz Manga app | iPad 2, iOS 4.3 – For quite some time now, I’ve stood by quietly as my esteemed colleagues raved about Mitsuru Adachi’s Cross Game. I meant to catch up, truly I did, but as more time (and more volumes) passed me by, the idea of catching up at $15-$20 a pop seemed more than a bit daunting. Fortunately, the Viz iPad app has changed all that, offering me the opportunity to buy these volumes for half their print price, and on a terrific platform to boot!

Cross Game, Omnibus Vol. 1 (Japanese vols. 1-3) | By Mitsuru Adachi | Viz Manga app | iPad 2, iOS 4.3 – For quite some time now, I’ve stood by quietly as my esteemed colleagues raved about Mitsuru Adachi’s Cross Game. I meant to catch up, truly I did, but as more time (and more volumes) passed me by, the idea of catching up at $15-$20 a pop seemed more than a bit daunting. Fortunately, the Viz iPad app has changed all that, offering me the opportunity to buy these volumes for half their print price, and on a terrific platform to boot! Veronica Presents: Kevin Keller, Issue 2 | By Dan Parent | Archie Comics App | iPad 2, iOS 4.3 – Comic creators who work in a shared universe face specific, conjoined responsibilities when adding a new character to that universe: they have to simultaneously generate interest in the addition while reassuring the existing audience that they aren’t going to go too far off of the ranch. The situation poses some interesting challenges, and success stories aren’t exactly numerous. One noteworthy example is the addition of a gay teen, Kevin Keller, to the wholesome solar system that is Archie Comics.

Veronica Presents: Kevin Keller, Issue 2 | By Dan Parent | Archie Comics App | iPad 2, iOS 4.3 – Comic creators who work in a shared universe face specific, conjoined responsibilities when adding a new character to that universe: they have to simultaneously generate interest in the addition while reassuring the existing audience that they aren’t going to go too far off of the ranch. The situation poses some interesting challenges, and success stories aren’t exactly numerous. One noteworthy example is the addition of a gay teen, Kevin Keller, to the wholesome solar system that is Archie Comics.

MICHELLE: I read a fair bit, but it was takoyaki-free. This included volumes six and seven of

MICHELLE: I read a fair bit, but it was takoyaki-free. This included volumes six and seven of  MJ: Well, I started off my week with the final volume of Kaneyoshi Izumi’s

MJ: Well, I started off my week with the final volume of Kaneyoshi Izumi’s  So, we’ve both read the next selection, and given your opinion of

So, we’ve both read the next selection, and given your opinion of