This weekend’s Nor’easter provided me a swell opportunity to finish my long-gestating Best and Worst Manga list for 2023. One of the things that tripped me up was the sheer volume of new work published last year; when I first started reviewing manga in 2006, it was hard to imagine a market that offered a title for every conceivable reader, from the Chainsaw Man enthusiast to the the romantic, the oenophile, the foodie, the soccer fan, the gore hound, the isekai buff, and even the middle-aged manga critic. Though I made a concerted effort to be as thorough as possible, I freely admit that my picks barely capture the sheer quantity and diversity of last year’s new releases. Instead, I focused on the titles that stayed with me weeks and months after I first read them, from the exuberant One Hundred Tales to the unnerving The Summer Hikaru Died. For additional perspective on 2023’s best and worst manga, I encourage you to check out the well curated lists at Anime News Network, Anime UK News, Asian Movie Pulse, The Beat, The Comics Journal, From Cover to Cover, Okazu, and The School Library Journal.

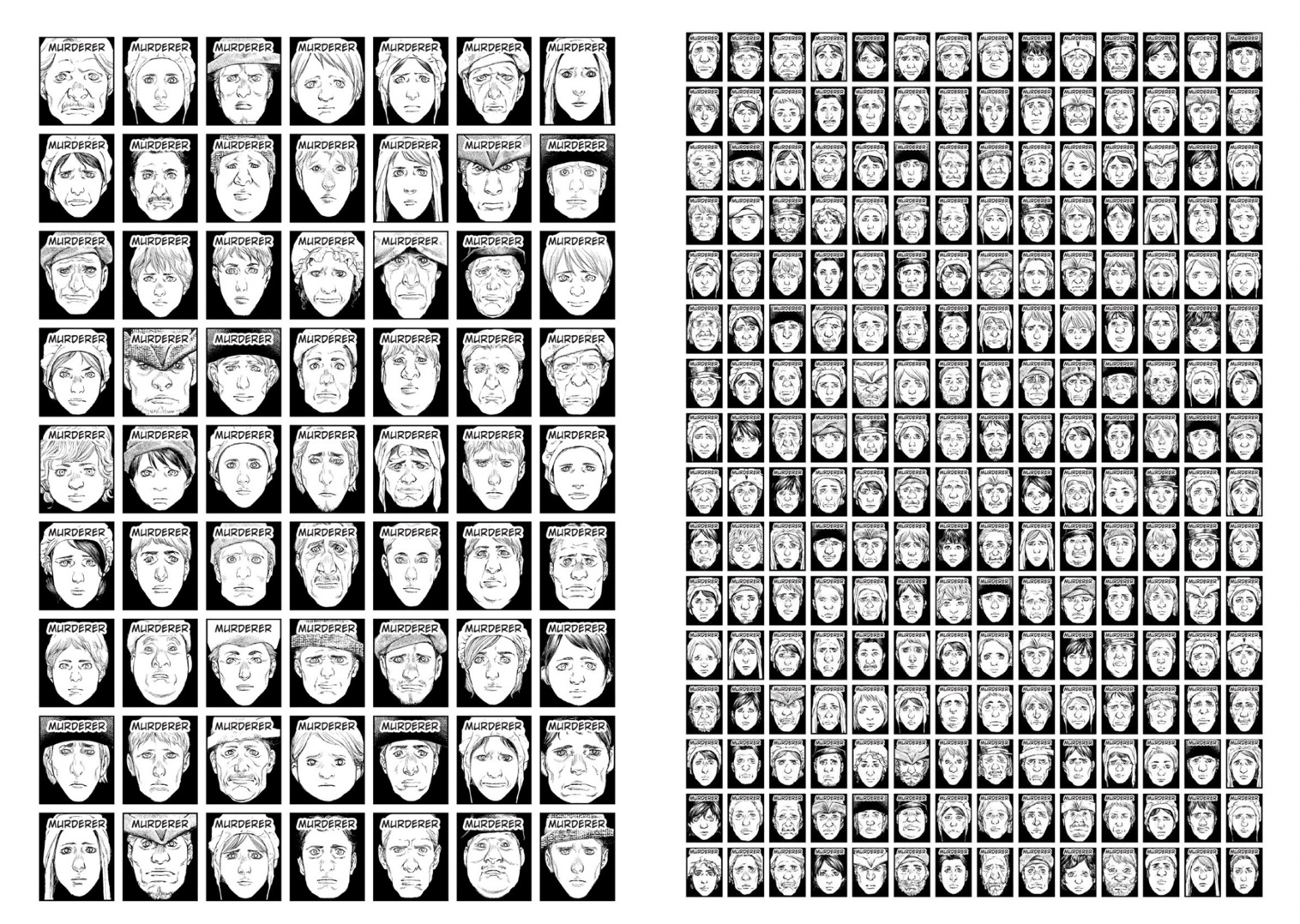

Best New Manga: Okinawa

Best New Manga: Okinawa

Story and Art by Susumu Higa • Translated by Jocelyne Allen • Lettering by Patrick Crotty and Kayla E. • Fantagraphics

There are books that critics like, and books that readers like. I’d put Okinawa squarely in the first category, as it has all the hallmarks of a Serious Manga™: slightly naïve artwork, historically important events seen through the eyes of ordinary people, and detailed footnotes explaining the story’s cultural and linguistic nuances. If I sound a little cynical, I was; I put off reading Okinawa for months after its release because so many reviewers rehearsed the same talking points about how “harrowing,” “heartbreaking,” “complex,” and “haunting” it was. After reading Okinawa, however, I have to admit the critics were right: Okinawa is a deeply moving exploration of the island’s fraught relationship with Japan and the United States. It’s also a tribute to Susumu Higa’s parents, whose memories of World War II pervade many of Okinawa’s most affecting stories; a celebration of Okinawan resilience and spirituality; and the best manga I read in 2023.

Best New Drama: River’s Edge“ Story and Art by Kyoko Okazaki • Translated by Alexa Frank • Vertical Comics

Story and Art by Kyoko Okazaki • Translated by Alexa Frank • Vertical Comics

River’s Edge offers a gritty portrait of adolescence before chat rooms, cell phones, and social media, focusing on the slackers and misfits at a Tokyo high school. Haruna Wakakusa, the protagonist, is caught between her fierce sense of justice and her ambivalent feelings towards her on-again, off-again boyfriend Kannonzaki, a horny, hot-headed loser who bullies weaker classmates. Over the course of the story, Haruna forges an unlikely friendship with one of Kannonzaki’s targets, an aloof young man whose popularity with the girls belies his true sexual orientation. Okazaki’s spare, stylish linework is ideally suited to the material, as the character’s exaggerated facial features and ungainly proportions remind the reader of how confusing, weird, and uncomfortable it is to be on the physical cusp of adulthood. Okazaki also nails the casual cruelty and cluelessness of adolescence: her characters’ impulsiveness, selfishness, and inexperience often compel them to betray each other in small (and big) ways that feel true to life even when the plot teeters on the brink of melodrama.

Best Classic Title: One Hundred Tales

Best Classic Title: One Hundred Tales

Story and Art by Osamu Tezuka • Translated by Iyasu Adair Nagata • Lettering by Aidan Clarke • ABLAZE

Over the course of his long career, Osamu Tezuka published three series based on the legend of Doctor Faustus, among them One Hundred Tales (1971), which ran in Weekly Shonen Jump. Tezuka takes a few liberties with the original story: his hero is not a brilliant scholar in search of knowledge but a lowly samurai who’s been sentenced to death for his employer’s misdeeds. In a fit of desperation, he sells his soul to a witch and is reborn as Fuwa Usuto, a dashing young man who wants two things: love and power. What follows is a rowdy picaresque, as Fuwo ventures into the lair of an alluring demon, saves his daughter from an arranged marriage, and insinuates himself into the house of a foolish daimyo in his quest to become more worldly and powerful. These episodes provide Tezuka ample opportunity to insert pop-cultural sight gags—Christopher Lee and Astro Boy both make fleeting appearances—but they also showcase Tezuka’s flair for character design and panel structure; the artwork is fluid and playful, equally suited to moments of exquisite silliness and heartbreaking sadness as Fuwo stumbles towards transcendence.

Best New Horror Series: The Summer Hikaru Died

Best New Horror Series: The Summer Hikaru Died

Story and Art by Mokumokuren • Translated by Ajani Oloye • Lettering by Abigail Blackman • Yen Press

The Summer Hikaru Died begins with a familiar scene: two high school buddies are clowning around outside a convenience store, trading good-natured barbs. But something’s off, and midway through a seemingly ordinary conversation Yoshiki realizes that he’s talking to an impostor who’s the spitting image of his friend Hikaru. Though the mystery of what happened to the real Hikaru is resolved quickly, many questions remain: is it possible for Yoshiki to befriend “Hikaru” even though he has no real memories of their relationship? And what, exactly, is “Hikaru”? Mokumokuren resists the temptation to provide simple answers, relying instead on suggestion to create a tense, atmospheric story that skillfully blends elements of body horror, BL, and fantasy in a fresh, unsettling way.

Best New Cat Manga: Nights With a Cat

Best New Cat Manga: Nights With a Cat

Story and Art by Kyuryu Z • Translated by Stephen Paul • Lettering by Lys Blakesly • Yen Press

Though there are dozens of great pet manga now available in English, Nights with a Cat has something genuinely new to offer: simple, observational storytelling that doesn’t shamelessly tug on the heartstrings or anthropomorphize our furry companions. The series explores the relationship between Fuuta and Kyuruga, his roommate’s cat. As someone who’s never lived with a cat before, Fuuta is fascinated by Kyuruga, marveling at Kyuruga’s anatomy—his pupils, his sandpaper tongue, his retractable claws—as well as Kyuruga’s ability to silently materialize in surprising places. Kyuryu Z doesn’t play these moments for laughs, choosing instead to emphasize how strange and amazing cats really are with illustrations that capture the fluidity of Kyuruga’s movements and the changeability of his moods. Recommended for new and long-time cat owners alike. (Reviewed at Manga Bookshelf on 5/21/23)

Best Ongoing Series: Go With the Clouds, North by Northwest

Best Ongoing Series: Go With the Clouds, North by Northwest

Story and Art by Irie Aki • Translated by David Musto • Vertical Comics

After a two-year wait, a new installment of Go With the Clouds, North by Northwest arrived in stores this fall, demonstrating once again why this odd, delightful, and occasionally thrilling story deserves a bigger audience. Strictly speaking, Go With the Clouds is a murder mystery, but Aki Irie refuses to observe the basic tenets of the genre, frequently interrupting her story for interesting diversions: a fitful romance between supporting characters, a brief lesson on Icelandic geography, a casual conversation between Kei, the main protagonist, and his trusty jeep. What prevents the story from being twee or mannered is its matter-of-fact tone. In the first chapter of volume six, for example, Kei uses ESP to track a kidnapping victim through the streets of Reykjavik by chatting up parked cars around the city, a goofy gambit that works thanks to Irie’s superb pacing and commitment to character development; Kei’s methodical approach suggests that his ESP is something he uses on an everyday basis, not something that manifests per the plot’s demands. Swoon-worthy art and twisty plotting add to the series’ considerable appeal. (Volumes one and two reviewed at The Manga Critic on 8/30/19).

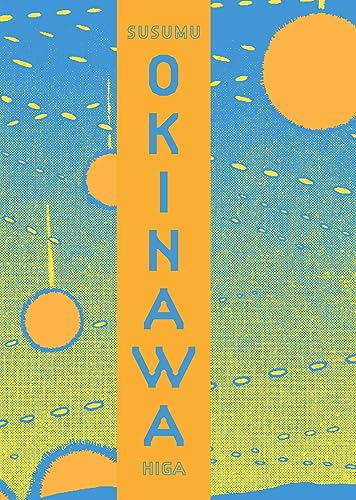

Most Disappointing New Series: #DRCL: Midnight Children

Most Disappointing New Series: #DRCL: Midnight Children

Story and Art by Shin’ichi Sakamoto • Based on Bram’s Stoker’s Dracula • Translation Caleb Cook • Touch-Up & Lettering by Brandon Hull • VIZ Media

Let’s face it: Bram Stoker’s Dracula sucks, marred by turgid prose and a convoluted form. In the hands of other creators, however, Stoker’s ideas have thrilled, titillated, and shocked six generations of horror buffs. The introduction to #DRCL: Midnight Children suggests that Shin’ichi Sakamoto might be one of those creators, as he offers the reader a claustrophobic, suspenseful riff on Dracula‘s most famous chapter, “The Voyage of the Demeter.” The rest of volume one, by contrast, is a fever dream of short, incoherent scenes that bump up against each other like commuters on a rush-hour train. Anyone familiar with Stoker’s original novel will recognize the characters’ names but wonder why Sakamoto re-imagined Renfield as a nun who’s chained up in a dormitory room or Mina Murray as a short, scrappy redhead who’s an expert wrestler. (Also: a dead ringer for Anne of Green Gables.) It’s a pity that the story is so fragmented and overripe, as Sakamoto has a fertile imagination; the first volume is filled with hauntingly beautiful renditions of Dracula himself that instill a sense of awe and fear that’s missing from the rest of the story.

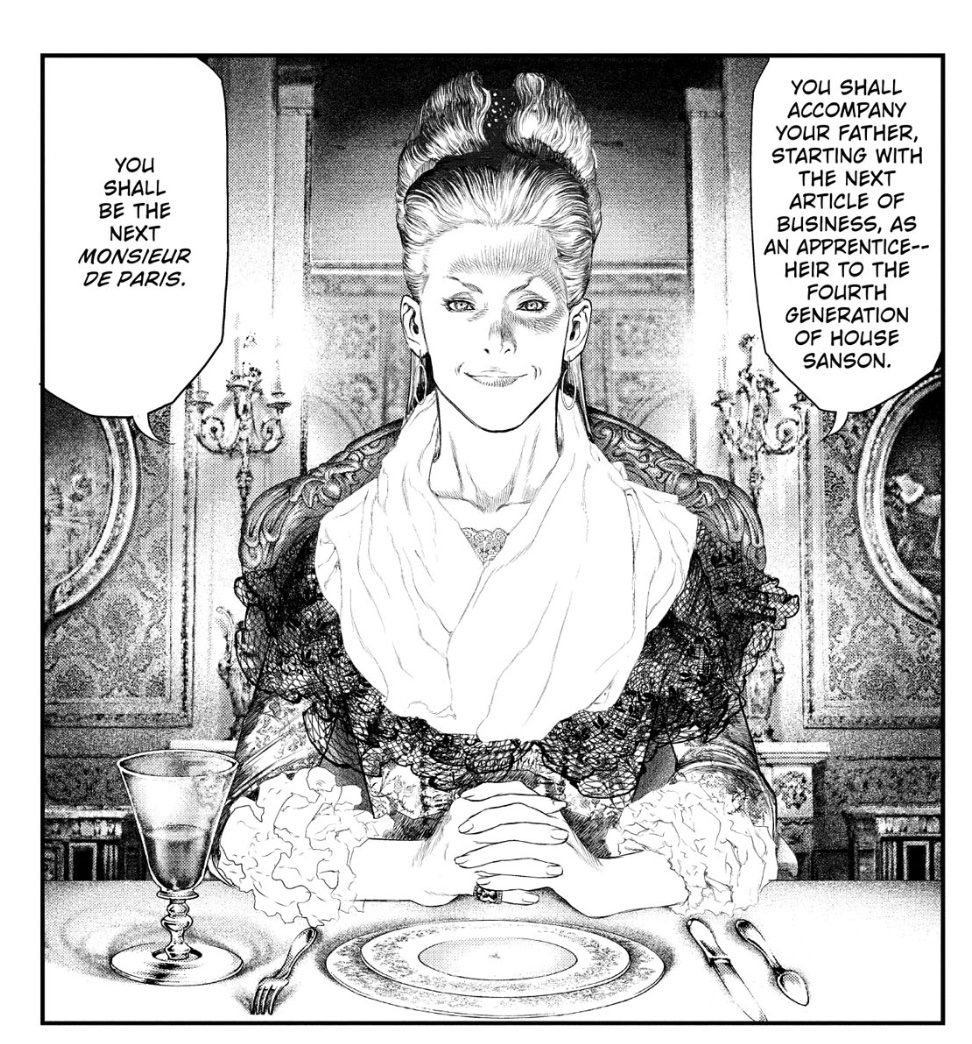

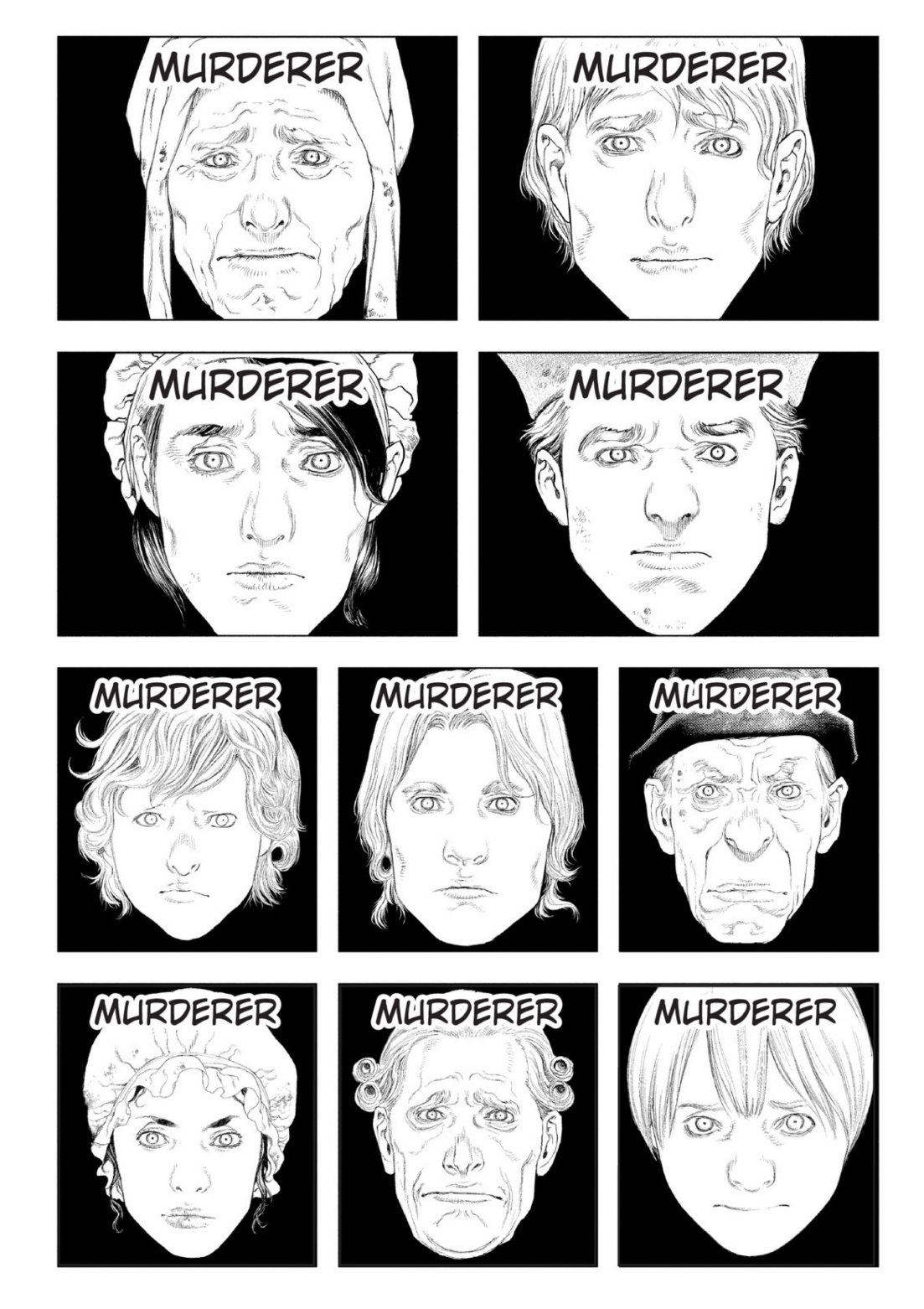

Sakamoto then repeats this motif, adding more and more faces:

Sakamoto then repeats this motif, adding more and more faces: