The irony this month is thick. I have been reading IKKI magazine for approximately three years and in that time I have not managed to review it. Now that my reason for reading it is gone, I finally am taking the time to review it…just before I stop getting it regularly.

The irony this month is thick. I have been reading IKKI magazine for approximately three years and in that time I have not managed to review it. Now that my reason for reading it is gone, I finally am taking the time to review it…just before I stop getting it regularly.

In fact, part of the reason I have not been able to review it was because I was reading it monthly for a series that is unlikely to make it over here in English, but is nonetheless the best manga I have ever read. It left me emotionally spent with every issue, so I couldn’t just sit down and write about it, or the magazine.

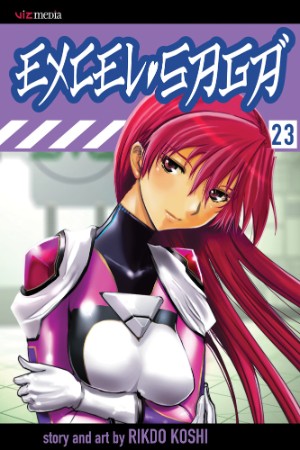

IKKI is relatively well-known to American readers, as Viz Media has an imprint of titles specifically coming from IKKI, known as SigIKKI. These titles include Childen of the Sea (Daisuke Igarashi), Afterschool Charisma (Kumiko Suekane), Kingyo Used Books (Seimu Tsuchida), House of Five Leaves (Nastume Ono), Saturn Apartments (Hisae Iwaoka), Dorohedoro (Q Hayashida) and Bokurano Ours (Mohiro Kitoh). These have been covered by many English-language manga reviewers, so I hope you don’t mind if I skip covering them. Another title that ran in IKKI that might be familiar to the English-reading audience is Iou Kuroda’s Sexy Voice and Robo.

Less well known to western audiences are other currently running series; of note Est Em’s “Golodrina,” about a woman who is being trained to become a matador; “Sex Nyanka Kyouminai” by the team of Kizuragi Akira and Satou Nanki, Banchi Kondo’s manga about baseball “Bob to Yuukaina Nakamatachi 2010,” and the reason I read IKKI at all, “GUNJO,” by Nakamura Ching, among many, many other series.

The general feel of IKKI is not terribly light-hearted. It’s a dark magazine, with dark roots and bits of dark stories popping up all over the place. It’s so dark at times, in fact, that as one reads a relatively innocent story, like “Ai-chan” or “Stratos”, one keeps waiting for the boot to drop and something awful to happen. Post apocalyptic life and murder sit comfortably next to unstable clones and gritty tales of survival in extreme circumstances.

IKKI has a website in Japanese, with sample chapters, featured messages from the manga artists and a list of shops where current volumes are available. SigIKKI also has a website in English where there are previews and downloads available for series that are carried under the imprint. At 550 yen ($6.60 at time of writing) for about 430 pages, IKKI costs just a few cents per page of entertainment.

IKKI is undoubtedy a magazine for adult readers of comics. It’s not that there’s sex, but that the themes are more about life – survival, even – in a variety of circumstances. A fan of Dostoevsky would be comfortable with the level of instrospection and conflict in this magazine. IKKI falls solidly into my “fifth column” of manga, if only for the lack of feel-good, team-oriented heroes fighting the good fight. IKKI is the dark side of seinen, away from the guns and running along rooftops, and closer to the quite desperation of making the best of a bad situation.

IKKI from Shogakukan: http://www.ikki-para.com/index.html