Have spirit gun, will travel — that’s the basic plot of Mail, a three-volume collection of ghost stories penned by Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service illustrator Housui Yamazaki.

Have spirit gun, will travel — that’s the basic plot of Mail, a three-volume collection of ghost stories penned by Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service illustrator Housui Yamazaki.

Like Kurosagi, Mail follows a spook-of-the-week formula, pausing occasionally to fill us in on the personal life of its chief exorcist, Detective Reiji Akiba. Akiba initially presents as a Columbo-esque figure, disarming clients with his rumpled coat and penchant for napping on the job, but his true nature is soon revealed in the first story: he’s handy with Kagutsuchi, his trusty pistol, and unflappable in the presence of the undead.

As we learn over the course of the series, Akiba was blind as a child. Medicine restored his sight, but with a side effect: he saw dead people. After years of living in fear of ghosts, Akiba learned to perform exorcisms with Kagutsuchi, a skill he parlayed into a career as a modern-day onmyoji.

If Akiba’s strategies for assisting his clients are decidedly hi-tech — websites, cellphones, GPS devices, bullets — the stories have a pleasantly old-fashioned quality to them. Some are morality plays; in “The Doll,” for example, a toy becomes the vessel for a hit-and-run victim to bring her killer to justice. Others read more like good campfire tales; in “Suppressed,” for example, a young woman begins receiving mysterious calls from a “friend” who’s en route to her home, the last of which appear to be originating from inside her apartment. Still others draw on urban legend for inspiration; “Ka-tsu-mi,” the fifth chapter in the series, focuses on a girl who dies after accidentally photographing a ghost.

I’d be the first to admit that Yamazaki is not a master of suspense. Though Mail is filled with suitably gruesome imagery and creative variations on oft-told ghost stories, the reader is never in doubt about Akiba’s ability to save his clients. The endings have a sameness that becomes more apparent when reading them back-to-back, as Akiba’s only method for banishing the undead is to fire Kagutsuchi. And while Akiba demonstrates remarkable sangfroid when confronting murdered babies, vengeful lovers, and drowning victims, his undeniable coolness doesn’t quite compensate for the predictability of the denounements.

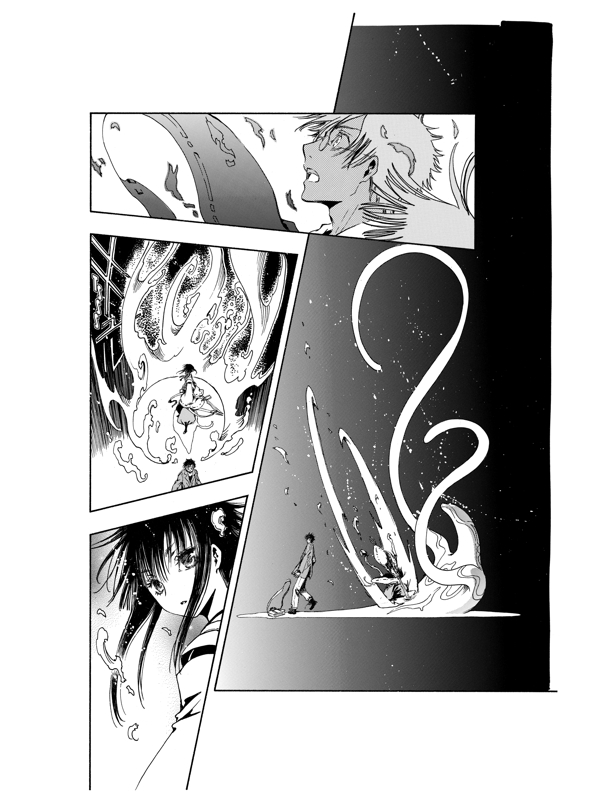

What Mail lacks in suspense it makes up in atmosphere. Yamazaki shows considerable flair for turning ordinary urban environments into unbearably scary places, whether he’s depicting an empty public bathroom or a high-rise building. In one of Mail‘s best stories, for example, a woman receives a letter urging her to move out of her apartment right away. Shortly after reading the letter, she catches glimpse of something moving along the ceiling of the adjacent room:

Though we’re outside the picture plane, viewing the action from a different angle than the hapless apartment dweller, we don’t have any more information about what’s lurking in the other room than she does; Yamazaki is relying on the reader to guess what might be crawling along the ceiling by planting one suggestive detail.

The other thing that makes this image so unsettling is the very mundaneness of the setting. With its square rooms and bland furnishings, this scene could be unfolding in almost any Tokyo neighborhood, in almost any modern apartment complex. (Add a parquet floor, and it could just as easily be taking place in any postwar building in Manhattan.) More unsettling still is that this scene is taking place in broad daylight, not at night; whatever is haunting the apartment isn’t relying on the camouflage of darkness, but is sallying forth at a time of day when spirits are supposed to be hidden and, more importantly, impotent.

Not all of the stories take place in Tokyo; several unfold in the countryside. Mail is at its best in urban settings, however, as the very nature of city living gives Yamazaki ample material to work with, whether he’s spinning a cautionary tale about the anonymity of modern life or simply reflecting on the myriad layers of history buried underneath new roadways and buildings. As a life-long city-dweller, I found stories such as “The Drive” — which takes place on an urban freeway — “The Elevator” — which takes place in a stalled elevator car — and “Hide-and-Seek” — which takes place in a haunted apartment — among the spookiest in the collection, as they tapped into a deep well of fear that all urban folk share: that cities harbor something even bigger and scarier than crime, high property taxes, or gridlock.