The next time someone dismisses manga as a “style” characterized by youthful-looking, big-eyed characters with button noses, I’m going to hand them a copy of AX, a rude, gleeful, and sometimes disturbing rebuke to the homogenized artwork and storylines found in mainstream manga publications. No one will confuse AX for Young Jump or even Big Comic Spirits; the stories in AX run the gamut from the grotesquely detailed to the playfully abstract, often flaunting their ugliness with the cheerful insistence of a ten-year-old boy waving a dead animal at squeamish classmates. Nor will anyone confuse Yoshihiro Tatsumi or Einosuke’s outlook with the humanism of Osamu Tezuka or Keiji Nakazawa; the stories in AX revel in the darker side of human nature, the part of us that’s fascinated with pain, death, sex, and bodily functions.

Founded in 1997, AX was a direct descendant of Garo (1964-2002), Katsuichi Nagai’s seminal avant garde manga magazine. As historian Paul Gravett explains in his introduction to A Collection of Alternative Manga, both publications served an essential purpose, providing artists a place to break free of the influence of commercial manga publishing — its rigid house styles, tight deadlines, strong editorial presence, and reader polls — and find more idiosyncratic forms of expression. At the same time, Gravett argues, Garo and AX gave artists a platform for speaking out against the dominant culture, to loudly question the truth that everyone can and should be “doing one’s best” while trying hard to fit in.

The thirty-three stories in A Collection of Alternative Manga nicely illustrate Gravett’s thesis, encompassing a true diversity of styles and subject-matters. At one end of the spectrum are artists such as Yuka Goto, whose work reflects a heta-uma, or “bad-good” aesthetic, with crudely-drawn figures in absurd situations (her feuding neighbors resolve their differences with a judo match), while at the other are artists such as Takato Yamato, whose intricate, naturalistic style becomes a vehicle for juxtaposing pornographically beautiful human bodies with explicit images of decay and rot. Most of the work in AX falls somewhere in between: the magical realism of Akina Kondo (“Rainy Day Blouse and The Umbrella”); the primitivist abstraction of Otoya Mitsusashi (“Sacred Light”); the horror-comedy of Kazuichi Hanawa (“Six Paths of Wealth”); the kawaii-grotesque of Mimyo Tomozawa (“300 Years”). Then there are stories which are parodies in the truest sense, borrowing the visual language of shonen manga for dark farce: Namie Fujieda’s “The Brilliant Ones,” in which an earnest group of students tries to help the class loser find a way to shine — even after his body has exploded into a thousand small parasites — and Tomohiro Koizumi’s “Stand By Me,” a story about a pair of peeping teens caught in the act.

For me, the biggest obstacle to enjoying the collection — as opposed to appreciating it — is that for every story like Ayuke Akiyama’s lovely, folkloric “In the Gourd” or Toranasuke Shimada’s historical phantasmagoria “Enrique Kobayashi’s El Dorado,” there are two that read like stunts, deliberate attempts to provoke, and maybe even disgust, the audience by rubbing its nose in taboo subjects and uncomfortable truths. Such confrontational art can be thought-provoking, to be sure, making us reconsider socially determined categories such as “parent,” “teacher,” and “child”: Yusaku Hanakuma’s “Puppy Love” is one such example, a bizarre, funny, upsetting story in which a woman gives birth to a litter of puppies and resolves to raise them as normal children. The struggles she and her “sons” face remind us of how difficult it is for anyone to raise a child whose behavior or appearance makes others uncomfortable; it’s With the Light, minus the easy sentiment (and with a dollop of David Cronenberg’s perverse sense of humor).

The need to elicit a strong, visceral response from the reader can also inspire puerile excess. Shigiheru Okada (“Me”), Saito Yunosuke (“Arizona Sizzler”), Kataoko Toyo (“The Ballad of Non-Stop Farting”), and Takashi Nemoto’s (“Black Sushi Party Piece”) repeated depictions of body parts and bodily fluids reminded me of sixth graders testing out every permutation of a new swearword to see which ones had the greatest shock value. Other stories, such as Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s “Lover’s Bride,” inspire an immediate ewwwww, and maybe a chuckle, but not much else: what deeper truths could possibly be gleaned from a sad-sack character’s decision to woo a primate instead of a human?

My other stumbling block to fully embracing AX is the way in which female characters are depicted in stories such as Yuichi Kiriyama’s “A Well-Dressed Corpse,” Hiroji Tani’s “Alraune Fatale,” and Osamu Kanna’s “The Watcher.” The female characters often seem more like receptacles for male anger, sexual aggression, or disappointment than they do actual human beings. I suppose one could argue that these artists are simply exaggerating a tendency found in manga across the spectrum, making explicit what’s normally implicit in a lot of material directed at male audiences. Yet none of these artists seem to be critiquing the male gaze in any meaningful way; they cast a pitiless, often lascivious eye on their female subjects, reducing them to a monstrous assortment of breasts and mouths and legs. It’s to editor Sean Michael Wilson’s great credit that he includes so many distinctive female voices in the anthology as well, preventing AX from becoming too dourly macho or grossly juvenile.

Yet for all my discomfort and distance from the material, I can’t look away. As a historian, AX excites me, providing a meticulously curated introduction to Japan’s underground comics scene. As a reader, AX challenges me to move beyond my notion of what constitutes manga, helping me understand what artists like Yoshihiro Tatsumi and Yoshiharu Tsuge were trying to do in the 1950s and 1960s with their “manga that isn’t manga”: to push the medium outside its comfort zone, to show us ugly truths, to make us laugh with recognition and discomfort, and to encourage artistic expression that, in Gravett’s words, is “as personalized as handwriting or a signature.” Recommended.

Review copy provided by Top Shelf. AX, Vol. 1: A Collection of Alternative Manga will be released on July 15, 2010.

AX, VOL. 1: A COLLECTION OF ALTERNATIVE MANGA • EDITED BY SEAN MICHAEL WILSON, WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY PAUL GRAVETT • TOP SHELF • NO RATING • 400 pp.

The next time someone dismisses manga as a “style” characterized by youthful-looking, big-eyed characters with button noses, I’m going to hand them a copy of AX, a rude, gleeful, and sometimes disturbing rebuke to the homogenized artwork and storylines found in mainstream manga publications. No one will confuse AX for Young Jump or even Big Comic Spirits; the stories in AX run the gamut from the grotesquely detailed to the playfully abstract, often flaunting their ugliness with the cheerful insistence of a ten-year-old boy waving a dead animal at squeamish classmates. Nor will anyone confuse Yoshihiro Tatsumi or Einosuke’s outlook with the humanism of Osamu Tezuka or Keiji Nakazawa; the stories in AX revel in the darker side of human nature, the part of us that’s fascinated with pain, death, sex, and bodily functions.

The next time someone dismisses manga as a “style” characterized by youthful-looking, big-eyed characters with button noses, I’m going to hand them a copy of AX, a rude, gleeful, and sometimes disturbing rebuke to the homogenized artwork and storylines found in mainstream manga publications. No one will confuse AX for Young Jump or even Big Comic Spirits; the stories in AX run the gamut from the grotesquely detailed to the playfully abstract, often flaunting their ugliness with the cheerful insistence of a ten-year-old boy waving a dead animal at squeamish classmates. Nor will anyone confuse Yoshihiro Tatsumi or Einosuke’s outlook with the humanism of Osamu Tezuka or Keiji Nakazawa; the stories in AX revel in the darker side of human nature, the part of us that’s fascinated with pain, death, sex, and bodily functions. Reading The Times of Botchan reminded me of watching Alexander Sakurov’s cryptic 2002 film

Reading The Times of Botchan reminded me of watching Alexander Sakurov’s cryptic 2002 film

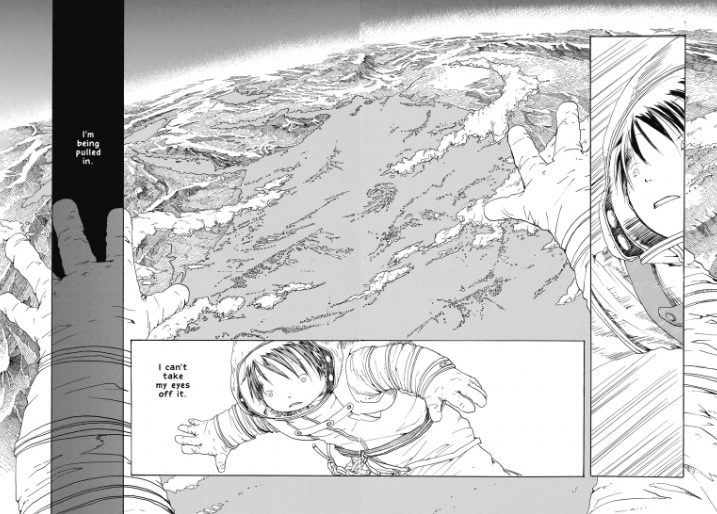

If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again.

If I’ve learned anything from my long love affair with science fiction, it’s this: there’s no place like home. You can boldly go where no man has gone before, you can explore new worlds and new civilizations, and you can colonize the farthest reaches of space, but you risk losing your way if you can’t go back to Earth again. The frog who appears to be a prince is a staple character in romantic comedies: what Jane Austen novel didn’t feature a handsome, wealthy suitor who, in the final pages of the story, turned out to be ethically challenged, penniless, or engaged to someone else? My Girlfriend’s a Geek offers a more up-to-the-minute version of Mr. Willoughby, this time in the form of a nice young woman who looks like a dream and holds down a responsible job, but has some rather unsavory habits of mind.

The frog who appears to be a prince is a staple character in romantic comedies: what Jane Austen novel didn’t feature a handsome, wealthy suitor who, in the final pages of the story, turned out to be ethically challenged, penniless, or engaged to someone else? My Girlfriend’s a Geek offers a more up-to-the-minute version of Mr. Willoughby, this time in the form of a nice young woman who looks like a dream and holds down a responsible job, but has some rather unsavory habits of mind. Asumi Kamogawa is a small girl with a big dream: to be an astronaut on Japan’s first manned space flight. Though she passes the entrance exam for Tokyo Space School, she faces several additional hurdles to realizing her goal, from her child-like stature — she’s thirteen going on eight — to her family’s precarious financial position. Then, too, Asumi is haunted by memories of a terrible fire that consumed her hometown and killed her mother, a fire caused by a failed rocket launch. Yet for all the pain in her young life, Asumi proves resilient, a gentle girl who perseveres in difficult situations, offers friendship in lieu of judgment, and demonstrates a preternatural awareness of life’s fragility.

Asumi Kamogawa is a small girl with a big dream: to be an astronaut on Japan’s first manned space flight. Though she passes the entrance exam for Tokyo Space School, she faces several additional hurdles to realizing her goal, from her child-like stature — she’s thirteen going on eight — to her family’s precarious financial position. Then, too, Asumi is haunted by memories of a terrible fire that consumed her hometown and killed her mother, a fire caused by a failed rocket launch. Yet for all the pain in her young life, Asumi proves resilient, a gentle girl who perseveres in difficult situations, offers friendship in lieu of judgment, and demonstrates a preternatural awareness of life’s fragility. Among the most discussed scenes in the new Kick-Ass film is one that pits a tweenage assassin against a roomful of grown men. To the strains of The Banana Splits theme song, thirteen-year-old Hit Girl dispatches a dozen gangsters with a gory zest that has divided critics into two camps: those, like Richard Corliss, who found the scene shocking yet exhilarating, a purposeful, subversive commentary on superhero violence, and those, like Roger Ebert, who found it morally reprehensible, a kind of kiddie porn that exploits the character’s age for cheap thrills. What’s at issue here is not children’s capacity for violence; anyone who’s run the gauntlet of a junior high cafeteria or cranked out an essay on Lord of the Flies is painfully aware that kids can be beastly when the grown-ups aren’t looking. The real issue is that Hit Girl seems to be enjoying herself, raising the far more uncomfortable question of how children understand and wield power.

Among the most discussed scenes in the new Kick-Ass film is one that pits a tweenage assassin against a roomful of grown men. To the strains of The Banana Splits theme song, thirteen-year-old Hit Girl dispatches a dozen gangsters with a gory zest that has divided critics into two camps: those, like Richard Corliss, who found the scene shocking yet exhilarating, a purposeful, subversive commentary on superhero violence, and those, like Roger Ebert, who found it morally reprehensible, a kind of kiddie porn that exploits the character’s age for cheap thrills. What’s at issue here is not children’s capacity for violence; anyone who’s run the gauntlet of a junior high cafeteria or cranked out an essay on Lord of the Flies is painfully aware that kids can be beastly when the grown-ups aren’t looking. The real issue is that Hit Girl seems to be enjoying herself, raising the far more uncomfortable question of how children understand and wield power. Kobato Hanato has a job to do: if she can fill a magic bottle with the pain and suffering of people whose lives she’s improved, she’ll have her dearest wish come true. There’s just one problem: Kobato is completely mystified by urban life, and has no idea how to identify folks in need of her help. Lucky for her, Ioryogi, a blue dog with a foul mouth and fierce temper, has been appointed her sensei and guardian angel, tasked with helping Kobato develop the the street smarts necessary for completing her mission.

Kobato Hanato has a job to do: if she can fill a magic bottle with the pain and suffering of people whose lives she’s improved, she’ll have her dearest wish come true. There’s just one problem: Kobato is completely mystified by urban life, and has no idea how to identify folks in need of her help. Lucky for her, Ioryogi, a blue dog with a foul mouth and fierce temper, has been appointed her sensei and guardian angel, tasked with helping Kobato develop the the street smarts necessary for completing her mission.