I have good news and bad news for CLAMP fans. The good news is that Gate 7 is one of the best-looking manga the quartet has produced, on par with Tsubasa: Reservoir Chronicles and xxxHolic. The bad news is that Gate 7‘s first volume is very bumpy, with long passages of expository dialogue and several false starts. Whether you’ll want to ride out the first three chapters will depend largely on your reaction to the artwork: if you love it, you may find enough visual stimulation to sustain to your interest while the plot and characters take shape; if you don’t, you may find the harried pacing and repetitive jokes a high hurdle to clear.

I have good news and bad news for CLAMP fans. The good news is that Gate 7 is one of the best-looking manga the quartet has produced, on par with Tsubasa: Reservoir Chronicles and xxxHolic. The bad news is that Gate 7‘s first volume is very bumpy, with long passages of expository dialogue and several false starts. Whether you’ll want to ride out the first three chapters will depend largely on your reaction to the artwork: if you love it, you may find enough visual stimulation to sustain to your interest while the plot and characters take shape; if you don’t, you may find the harried pacing and repetitive jokes a high hurdle to clear.

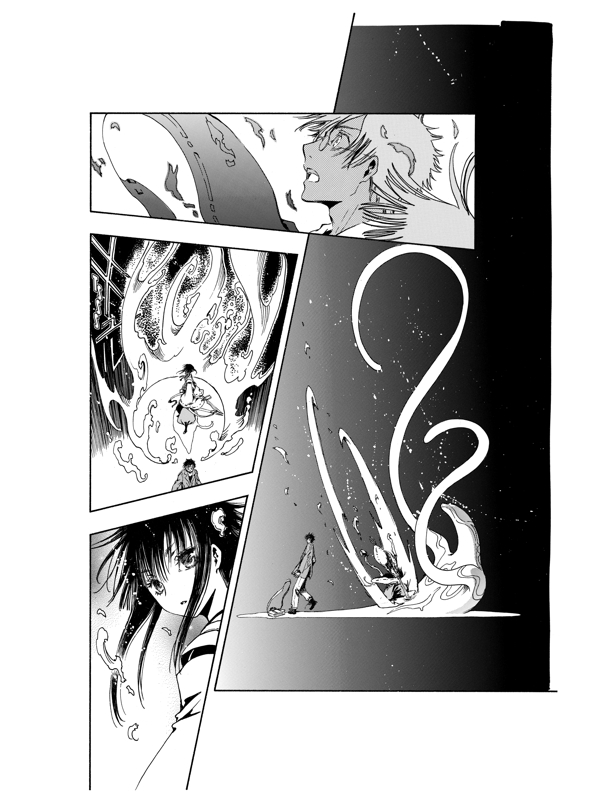

Art-wise, Gate 7 most closely resembles Tsubasa. The character designs are elegantly stylized, rendered in delicate lines; though their proportions have been gently elongated, their physiques are less giraffe-like than the principle characters in Legal Drug and xxxHolic. The same sensibility informs the action scenes as well, where CLAMP uses thin, sensual linework to suggest the energy unleashed during magical combat. (Readers familiar with Magic Knight Rayearth will see affinities between the two series, especially in the fight sequences.) Perhaps the most striking thing about the artwork is its imaginative use of water and light to evoke the supernatural. As Zack Davisson observes in his review of Gate 7, CLAMP uses a subtle but lovely image to shift the action from present-day Kyoto to the spirit realm, depicting the characters as stones in the water, with soft ripples radiating outward from each figure….