By Yuhta Nishio | Published by VIZ Media

In the opening scene of After Hours, Emi Asahina is attempting (unsuccessfully) to meet up with a friend in a loud and crowded nightclub. After a spunky DJ named Kei saves her from a grabby creep, they get to talking. Emi tells her, “I don’t really see what’s fun about places like this.” Much of the rest of the manga is Kei helping her to change her mind about that.

In the opening scene of After Hours, Emi Asahina is attempting (unsuccessfully) to meet up with a friend in a loud and crowded nightclub. After a spunky DJ named Kei saves her from a grabby creep, they get to talking. Emi tells her, “I don’t really see what’s fun about places like this.” Much of the rest of the manga is Kei helping her to change her mind about that.

Emi ends up going home with Kei that night, and they appear to have fooled around to some extent, though that’s left to the reader’s imagination. Instead, the focus is on Emi learning more about Kei’s world. The club scene is a new setting for me where manga is concerned, and imparts a unique feel. Emi is 24 and unemployed and she doesn’t know what she wants to do with her life, but after once getting roped in to providing visuals to accompany Kei’s music, she’s enthusiastic to try it a second time. Kei swiftly provides Emi the key to her apartment, and tells her things about her past that she usually doesn’t talk about, gives her records from her prized vinyl collection, etc. For all of her cool chick persona, Kei is open and honest and pretty awesome. And so, I’m kind of afraid she’s going to get her heart broken.

Because although Emi is having fun with Kei, there’s never really a sense that she’s choosing Kei as opposed to just sampling her lifestyle. After they maybe sleep together, there is not a single scene from Emi contemplating what this might mean about her sexuality. And, at the halfway point of the volume, we learn that she is living with the boyfriend she’s only “kind of” broken up with, and Kei has no idea. Is Emi going to make a decision about what she wants from life that will include Kei, or is this just tourism for her? Granted, the manga itself isn’t amping up the potential for drama here, so perhaps it will all play out in the relatively restrained way it has so far.

One thing I really liked about this volume was a scene in which Kei is showing Emi how to operate some DJ equipment. She explains how the inputs from two separate turntables can be adjusted to mix and segue into each other. Later, this metaphor is applied to their relationship. Kei is sharing a lot while Emi is revealing little. “If it’s all coming from my side, it’s not really mixing, is it?” she says. I thought that was a pretty neat idea. Really, my one complaint so far is that the characters look so young. Kei is supposed to be thirty, but looks fourteen. She still comes off as a vibrant and captivating, but I think her cool quotient would increase if she looked more like an adult.

Definitely looking forward to volume two!

After Hours is complete in three volumes. The second is due out in English next week.

Review copy provided by the publisher.

Although I was originally

Although I was originally

Neri Oishi was a great volleyball player in elementary school, when she was captain of a team that took second place in the national championship. At her prestigious middle school, however, she’s a benchwarmer, often tasked with picking up balls and doing laundry. One of her teammates, Chiyo, is vocally frustrated by the situation, since she played against Neri’s team and knows how good she is. After injuring Chiyo during an argument, Neri must play in her stead in a practice game. Try as she might to suppress them, her aggressive tendencies flare, and she ends up injuring a teammate. Disaster is further assured when her childhood friend/osteopath Shigeru chooses the boys’ bathroom as a treatment venue. Upon discovery (and subsequent misunderstanding), Neri is forced to resign from the volleyball club.

Neri Oishi was a great volleyball player in elementary school, when she was captain of a team that took second place in the national championship. At her prestigious middle school, however, she’s a benchwarmer, often tasked with picking up balls and doing laundry. One of her teammates, Chiyo, is vocally frustrated by the situation, since she played against Neri’s team and knows how good she is. After injuring Chiyo during an argument, Neri must play in her stead in a practice game. Try as she might to suppress them, her aggressive tendencies flare, and she ends up injuring a teammate. Disaster is further assured when her childhood friend/osteopath Shigeru chooses the boys’ bathroom as a treatment venue. Upon discovery (and subsequent misunderstanding), Neri is forced to resign from the volleyball club. Neri is ashamed of the selfish way she sometimes plays, and wants to change. She’s also absolutely certain that anyone trying to be friends with her is going to end up regretting it. To this end, she initially keeps her #1 fan, Manabu Odagiri, at a distance. Neri saved Manabu from bullies when they were kids, and Manabu has never forgotten it. It soon becomes clear that Manabu is now in the one in the position to help, urging Neri to try to talk to people instead of simply interpreting things in the worst way possible.

Neri is ashamed of the selfish way she sometimes plays, and wants to change. She’s also absolutely certain that anyone trying to be friends with her is going to end up regretting it. To this end, she initially keeps her #1 fan, Manabu Odagiri, at a distance. Neri saved Manabu from bullies when they were kids, and Manabu has never forgotten it. It soon becomes clear that Manabu is now in the one in the position to help, urging Neri to try to talk to people instead of simply interpreting things in the worst way possible. I haven’t read a ton of yuri manga, but even I have encountered the “all-girls school with multiple couples” setup before. Kiss & White Lily for My Dearest Girl is another example of the same.

I haven’t read a ton of yuri manga, but even I have encountered the “all-girls school with multiple couples” setup before. Kiss & White Lily for My Dearest Girl is another example of the same. Volume two introduces still more characters. Ai Uehara doesn’t endear herself to me by whining about the availability of third-year Maya Hoshino—“Mock exams are more important to you than I am!”—and the chapter where she tries to make her friend stay in town rather than going to the university of her dreams and then realizes that this makes her friend sad and then promptly trips and starts blubbering just about had steam coming out of my ears.

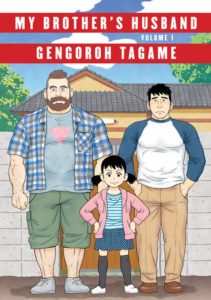

Volume two introduces still more characters. Ai Uehara doesn’t endear herself to me by whining about the availability of third-year Maya Hoshino—“Mock exams are more important to you than I am!”—and the chapter where she tries to make her friend stay in town rather than going to the university of her dreams and then realizes that this makes her friend sad and then promptly trips and starts blubbering just about had steam coming out of my ears.  Yaichi is a single dad who works from home managing the rental property his parents left to him and his brother, Ryoji, after being killed in a car accident when the boys were teenagers. He considers his real job to be providing the best home he can to his daughter, Kana. On the day the story begins, Yaichi is expecting a guest—Mike Flanagan, the burly Canadian whom Ryoji married after leaving Japan ten years ago. Ryoji passed away the previous month and Mike has come to Japan to try to connect with Ryoji’s past and see for himself the many things he’d heard stories about from his husband.

Yaichi is a single dad who works from home managing the rental property his parents left to him and his brother, Ryoji, after being killed in a car accident when the boys were teenagers. He considers his real job to be providing the best home he can to his daughter, Kana. On the day the story begins, Yaichi is expecting a guest—Mike Flanagan, the burly Canadian whom Ryoji married after leaving Japan ten years ago. Ryoji passed away the previous month and Mike has come to Japan to try to connect with Ryoji’s past and see for himself the many things he’d heard stories about from his husband. Although I genuinely, deeply love shounen sports manga, I can’t deny that most follow similar story beats. I knew going in that Giant Killing is actually seinen, but wasn’t prepared for what a breath of fresh air it would be.

Although I genuinely, deeply love shounen sports manga, I can’t deny that most follow similar story beats. I knew going in that Giant Killing is actually seinen, but wasn’t prepared for what a breath of fresh air it would be. In the opening scene of Wave, Listen to Me! we meet Minare Koda, an attractive twenty-something drinking too much and pouring her heart out to a guy she just met forty minutes prior. She’s ranting about her ex, Mitsuo, and after a certain point, she has no recollection of events. To her surprise, when she’s at work the next day (as a waitress in a curry shop), she hears her own voice being played over the radio. Turns out, the guy she met was Kanetsugu Mato, who works for a radio station and recorded their conversation. (One of the things she’d forgotten was drunkenly giving her consent.) Minare is temperamental and feisty, so when she marches down to the station to give him a piece of her mind, she ends up going live on the air and impressing Mato with her facility for impromptu eloquence.

In the opening scene of Wave, Listen to Me! we meet Minare Koda, an attractive twenty-something drinking too much and pouring her heart out to a guy she just met forty minutes prior. She’s ranting about her ex, Mitsuo, and after a certain point, she has no recollection of events. To her surprise, when she’s at work the next day (as a waitress in a curry shop), she hears her own voice being played over the radio. Turns out, the guy she met was Kanetsugu Mato, who works for a radio station and recorded their conversation. (One of the things she’d forgotten was drunkenly giving her consent.) Minare is temperamental and feisty, so when she marches down to the station to give him a piece of her mind, she ends up going live on the air and impressing Mato with her facility for impromptu eloquence. Volume two is where things really get great. Mato has inventive ideas for Minare’s show, and I think I will let readers discover those for themselves. What I really loved, though, was the continued exploration of Minare’s personality. For example, when she has the jitters and receives reassurance, she cries, “I can feel it rushing back! My usual baseless, overflowing confidence!” She might have come off as an unsympathetic and abrasive character, but that line shows that she’s fully aware of her flaws. Later, after a brief (and awesome) reunion with Mitsuo, she displays a knack for more self-analysis, reflecting that while she usually doesn’t take shit from anyone, she has a certain weakness for pathetic guys who need someone to dote over them. I expect that this capacity for reflection will allow her to make the most of the opportunity she’s been given.

Volume two is where things really get great. Mato has inventive ideas for Minare’s show, and I think I will let readers discover those for themselves. What I really loved, though, was the continued exploration of Minare’s personality. For example, when she has the jitters and receives reassurance, she cries, “I can feel it rushing back! My usual baseless, overflowing confidence!” She might have come off as an unsympathetic and abrasive character, but that line shows that she’s fully aware of her flaws. Later, after a brief (and awesome) reunion with Mitsuo, she displays a knack for more self-analysis, reflecting that while she usually doesn’t take shit from anyone, she has a certain weakness for pathetic guys who need someone to dote over them. I expect that this capacity for reflection will allow her to make the most of the opportunity she’s been given. Widowed math teacher Kohei Inuzuka wants to do his best when it comes to raising his daughter, Tsumugi. It’s been six months since his wife passed away, and because he has never had much of an appetite and hasn’t fared well with cooking in the past, he mostly relies on store-bought fare for Tsumugi. However, after they run into one of his students, Kotori Iida, while looking at cherry blossoms, he can’t help but notice how fascinated Tsumugi is by the home-cooked lunch Kotori’s been eating. To make his daughter happy, he ends up taking her to Kotori’s family restaurant, which leads to regular dinner parties where they experiment with making different things together.

Widowed math teacher Kohei Inuzuka wants to do his best when it comes to raising his daughter, Tsumugi. It’s been six months since his wife passed away, and because he has never had much of an appetite and hasn’t fared well with cooking in the past, he mostly relies on store-bought fare for Tsumugi. However, after they run into one of his students, Kotori Iida, while looking at cherry blossoms, he can’t help but notice how fascinated Tsumugi is by the home-cooked lunch Kotori’s been eating. To make his daughter happy, he ends up taking her to Kotori’s family restaurant, which leads to regular dinner parties where they experiment with making different things together. chawanmushi, and some seriously drool-inducing gyoza. Recipes are included, and for the first time, I feel like they’re actually something I might attempt.

chawanmushi, and some seriously drool-inducing gyoza. Recipes are included, and for the first time, I feel like they’re actually something I might attempt. He and Kotori maintain their distance at school, and he frequently worries about inconveniencing her mother. And yet, the gatherings make Tsumugi so happy—and even lift her spirits when she begins to truly comprehend the permanence of her mother’s absence—that he gratefully accepts the Iidas’ hospitality. He behaves professionally at all times. Kotori, however, seems to be developing feelings for him, though it’s all mixed up as she sees him as both a guy and as a father figure. I wouldn’t be surprised if the manga ends with them getting married, but I hope nothing romantic ensues for a very long time.

He and Kotori maintain their distance at school, and he frequently worries about inconveniencing her mother. And yet, the gatherings make Tsumugi so happy—and even lift her spirits when she begins to truly comprehend the permanence of her mother’s absence—that he gratefully accepts the Iidas’ hospitality. He behaves professionally at all times. Kotori, however, seems to be developing feelings for him, though it’s all mixed up as she sees him as both a guy and as a father figure. I wouldn’t be surprised if the manga ends with them getting married, but I hope nothing romantic ensues for a very long time. Fifteen kids—most of them, except for one boy’s kid sister, in 7th grade—are taking part in a summer program called “Seaside Friendship and Nature School.” Chafing at the instruction to go out and observe nature, the kids decide to explore a nearby cave, where they inexplicably discover a computer lab and a strange guy who calls himself Kokopelli.

Fifteen kids—most of them, except for one boy’s kid sister, in 7th grade—are taking part in a summer program called “Seaside Friendship and Nature School.” Chafing at the instruction to go out and observe nature, the kids decide to explore a nearby cave, where they inexplicably discover a computer lab and a strange guy who calls himself Kokopelli. Bokurano is structured similarly, focusing on each pilot as he or she “gets the call.” There are merits and flaws to this approach: obviously, the current pilot receives a lot of attention, and it’s interesting to see how each approaches the responsibility differently. One boy cares nothing for human casualties while another carefully takes the battle out into the harbor to minimize damage. One girl uses her final hours to sew morale-boosting uniforms for the group. Unfortunately, this also means that at any given time there are about a dozen characters relegated to the background, waiting for their turn to contribute to the story.

Bokurano is structured similarly, focusing on each pilot as he or she “gets the call.” There are merits and flaws to this approach: obviously, the current pilot receives a lot of attention, and it’s interesting to see how each approaches the responsibility differently. One boy cares nothing for human casualties while another carefully takes the battle out into the harbor to minimize damage. One girl uses her final hours to sew morale-boosting uniforms for the group. Unfortunately, this also means that at any given time there are about a dozen characters relegated to the background, waiting for their turn to contribute to the story.