Have you ever read a review that was so riddled with misspelled words, grammatical errors, or nonsensical phrases that you began to keep a mental tally of the gaffes instead of following the author’s argument? I have. And while it would be easy to make light of such reviews, I feel compassion for the writer. I’ve made more than my share of mistakes online, from misspelling an author’s name to penning a sentence so tortured that, in hindsight, I wasn’t even certain what I meant. The majority of these mistakes can be chalked up to one thing: failing to edit my work carefully. Deadlines, job pressures, and personal commitments can make it easy to neglect editing, but failing to do so can compromise your authority as a writer and a critic, and anger creators who want to see their work treated respectfully; it isn’t pretty to be called on the carpet for writing a negative review that’s as problematic as the book under consideration. (Believe me, I’ve seen it happen. In a word: aaawwwwwwwkward.)

Below, I’ve outlined the steps involved in editing a review. These suggestions reflect the many years I’ve spent honing my own writing as a student, a teacher, an editor, a writer, and a Gal Friday with proofreading chops. This outline is not intended to be a one-size-fits-all proscription for catching mistakes, but a tool to help writers develop their own process for assessing and improving their work. Have an online resource that you think would be helpful for writers? Let me know in the comments and I’ll update the post to include your suggestion.

How Do I Edit My Stuff?

Most writers equate editing with checking their work for cosmetic problems—typos, extra carriage returns, and so forth. And while it’s true that proofreading is an important step in the editorial process, it’s generally the final one. The first—and most difficult—stages require you to scrutinize your prose for clarity, consistency, and economy (namely, can you say something in 10 words instead of 15 or 20?). Here’s a rough outline of the steps entailed in editing an essay or story:

Step One: Set the draft aside for one or two days.

There may be times when this simply isn’t possible, but allowing yourself time between drafting and editing will improve your chances of spotting problems.

Step Two: Read the review out loud, asking yourself the following questions:

Do the sentences flow smoothly? Circle or highlight any sentence that sounds choppy or awkward—the grammar may need correction, the word order may need adjustment, or the sentence may need to be shortened.

Do you use the same words or phrases too often? Circle or highlight those passages, then grab a thesaurus and search for alternatives.

Do you needlessly repeat information or opinions? There’s a fine line between elaborating a point and belaboring it; if you’ve described a book as “exciting,” “pulse-pounding,” and “thrilling” all in the span of a single sentence, you’ve said the same thing three times.

Step Three: Make your first round of corrections, then re-read with an eye towards structural issues. Ask yourself the following questions:

Does my review flow seamlessly from point to point? Look for awkward phrases, abrupt transitions, and weak topic sentences.

Have I achieved an appropriate balance between summary and critique? Generally speaking, reviews should be no more than 50% summary. If in doubt, trim any information that may be viewed as a spoiler, or is not addressed in your subsequent critique of the manga.

Have I substantiated my critique with evidence from the volume(s) I’m reviewing? If you describe a book as “dull” or “irritating,” be sure to explain why you feel that way: is it the dialogue? A particular character? The obvious plot twists?

Does the overall tone of my review match my opinion of the book? If you enjoyed a book, that should be evident from your word choice; the same is true for books that you didn’t like. If you’re ambivalent about a title, it’s OK to say so in the opening or closing of your review.

The Discard File

One of the main reasons we have difficulty editing is that we become attached to a favorite sentence or paragraph. Having crafted something that we like, we’re reluctant to delete it no matter how clumsy or inappropriate it may be in context. I have a remedy for deletion anxiety: cut and paste the offending passage into a separate file. That way, you can retrieve a sentence that, on second judgment, seems useful to your argument. Or you can do the eco-friendly thing and recycle a great turn of phrase in a future article. My own discard file has been a terrific resource for overcoming writer’s block, improving a weak review, and preserving kick-ass sentences that amused me but might never see the light of day.

Proofreading Tips

Allow at least a few hours (if not longer) before you begin proofreading, or you’re bound to miss mistakes. I find it helpful to read the document backwards—the strangeness of the experience forces me to look at the prose more carefully, though the technique might not work for everyone.

I have a simple checklist of things to look for when I proofread:

- Extra spaces or carriage returns

- Spelling errors, typos (e.g. extra or missing letters)

- Subject-verb agreement (e.g. “They is” instead of “They are”), switching tense

- Its vs. it’s, which vs. that

- Punctuation and capitalization errors

- Missing words (e.g. forgetting an article, “In this volume, the family gets dog.”)

Two other things on my radar screen are parallelism problems and passive constructions. Most writers don’t realize that when they make a list of items, all of the items of the list need to be structured/phrased in the same manner, e.g. “Among the things she owned were a broken TV, a rotary phone, and a cracked mirror.” Note that all of the items in this list are expressed as article-adjective-noun. The same rule applies to sentences using participles and verbs, e.g. “He enjoys many activities, from playing golf and swimming to gardening and walking the dog.”

One of my other pet peeves as a writer is the kind of vagueness that goes hand-in-hand with passive constructions. Phrases such as “Urasawa is widely acknowledged as a genius” do more harm than good, as they leave your reader to wonder, Who says Urasawa is a genius? His critics? His mother? A better strategy is to rephrase these sentences in the active voice: “Urasawa’s fellow manga artists revere him as a genius.” There are, of course, plenty of times when the passive voice is a perfectly acceptable choice, especially in academic writing, but if it’s possible to identify an agent, do so. Your writing will sound more authoritative.

The final thing to keep in mind when proofreading: be consistent. If you give the name of one city as “Austin, TX,” all the cities in your essay should be formatted that way (as opposed to “Boston, Mass.” or “Yonkers, New York”). If you decide to hyphenate Asian-American, then all occurrences of that word should be hyphenated. And so forth. There are several excellent style manuals on the market (such as The Chicago Manual of Style and The MLA Handbook) that provide the nitty-gritty on hyphenation, capitalization, italicization, etc. Don’t want to shell out the clams for a bound copy? Many universities have posted Cliff Notes versions of these venerable style guides; one that I find useful in a pinch is The OWL (Online Writing Lab) at Purdue.

When Deadlines Loom…

Pressed for time? At a minimum, run the SpellCheck function on your computer, but monitor it carefully—the SpellChecker can add mistakes to your work, especially if you use funky foreign words like fujoshi or gensaku-sha. If these are words you anticipate using in future documents, add them to your SpellChecker’s memory to avoid comically awful substitutions. I’m less enthusiastic about Microsoft Word’s GrammarCheck function. While it seldom misses glaring errors (e.g. “You is my woman”), it may gloss over deeper structural problems or flag a sentence that is, in fact, grammatically acceptable. Use sparingly.

Putting Advice Into Practice

Suppose you’re writing a review of a new series, Dogball D. You’re both bored by and frustrated with the first volume, as the characters’ mannerisms and physical appearance remind you of characters from Dragonball Z. At the same time, however, you recognize that the similarity is intentional. The challenge: how to express that idea effectively.

Version 1: The main problem with Dogball D is that the characters are boring and unoriginal and just like the characters in Dragonball Z. That’s understandable, since Yuki Yamamoto wrote her story for a magazine that was competing directly with the magazine in which Dragonball Z was a big hit for many years before Dogball D came out.

Version 2: Dogball D‘s biggest problem is the characters: they’re pale imitations of the Dragonball Z gang. The similarity is understandable, since Yuki Yamamoto’s story runs in Young Mister, a direct competitor of the magazine in which Dragonball Z was serialized.

In the second version, I’ve compressed the idea of “boring” “unoriginal” characters into a single, more forcefully stated comparison between Dogball D and Dragonball Z. I’ve eliminated several prepositional phrases (e.g. “for a magazine”) and conjunctions, and dropped the phrase “before Dogball D came out,” as the contrast in tenses (“runs” versus “was serialized”) implies that Dragonball Z preceded Dogball D — an impression confirmed by the initial statement that the Dogball D cast is a “pale imitation” of Dragonball Z‘s famous characters. You can only imitate existing models!

Here’s another before-and-after comparison, this one culled from my own writing. The first paragraph comes from my review of Chica Umino’s Honey and Clover; the second comes from the revised version now currently visible on the front page. Changes are highlighted in red:

Original: If you’ve spent any time around an art school or conservatory, you’ve met students like the Honey and Clover gang, a chatty bunch who are eager to share and compare influences, discuss their romantic lives in intimate detail, and wax poetic about their latest enthusiasms. In Honey and Clover, that garrulity reflects the characters’ deep-rooted need for community, both a boundary-drawing exercise — this is what I stand for — and an invitation to join the group. As characters grow closer to each other, however, they often find conversation inadequate to the task of bridging the remaining distance between them, a motif that Chica Umino uses throughout volume eight.

Revised: If you’ve spent any time around an art school or conservatory, you’ve met students like the Honey and Clover gang, a chatty bunch who are eager to share and compare influences, discuss their romantic lives in intimate detail, and wax poetic about their latest enthusiasms. In Honey and Clover, that chattiness reflects the characters’ deep-rooted need to define who they are and how they fit in with their peers. As characters discover common ground, however, they often find conversation inadequate to the task of bridging the remaining distance between them, a motif that Chica Umino uses throughout volume eight.

I decided to revise the paragraph because I found it wordy and, frankly, a little pretentious: “garrulity”? “Boundary-drawing exercise”? The emptiness of those words became even more apparent when contrasted with the review that immediately followed it, as my take on Mixed Vegetables was snappier and easier to follow. So I rolled up my sleeves and made several small but crucial changes by finding five-dollar substitutes for the fifteen-dollar words and eliminating the parenthetical remark from the second sentence. The result: a clearer statement of the same idea.

Conclusion

I’ve learned as much from my errors as I have from my successes, as they remind me just how difficult writing really is. The more I practice drafting and editing my own work, however, the better the final product tends to be. Confronting my own shortcomings keeps me humble, but it also keeps me invested in improving, too — each review presents an opportunity to refine my skills a little more, and a chance to reflect on what constitutes good writing.

The very first Sinfest strips tell you everything you need to know about Tatsuya Ishida’s cheeky yet surprisingly reverential comic. In them, we see a young man seated at a table across from the Devil, negotiating a contract that would enable him to enjoy — among other perks — a “supermodel sandwich” in exchange for his soul. The transaction isn’t taking place in an office or the gates of Hell, however, but, in a hat tip to Charles Schulz, at a jerry-rigged booth that’s a shoo-in for the one Lucy van Pelt used to dispense nickel-sized bits of wisdom to the Peanuts gang.

The very first Sinfest strips tell you everything you need to know about Tatsuya Ishida’s cheeky yet surprisingly reverential comic. In them, we see a young man seated at a table across from the Devil, negotiating a contract that would enable him to enjoy — among other perks — a “supermodel sandwich” in exchange for his soul. The transaction isn’t taking place in an office or the gates of Hell, however, but, in a hat tip to Charles Schulz, at a jerry-rigged booth that’s a shoo-in for the one Lucy van Pelt used to dispense nickel-sized bits of wisdom to the Peanuts gang. From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

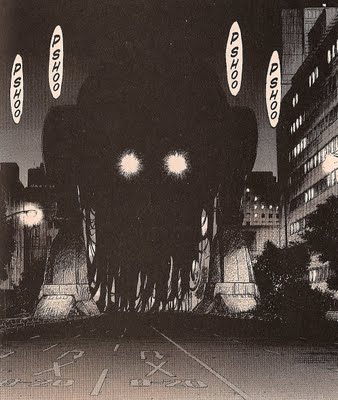

Do you remember those first, glorious seasons of Heroes and Lost? Both shows promised to reinvigorate the sci-fi thriller with complex, flawed characters and plots that moved freely between past, present, and future. By the middle of their second seasons, however, it was clear that neither shows’ writers knew how to successfully resolve the conflicts and mysteries introduced in the first, as the writers resorted to cheap tricks — the out-of-left-field personality reversal, the all-too-convenient coincidence, and the arbitrary let’s-kill-off-a-character plot twist — to keep the myriad plot lines afloat, alienating thousands of viewers in the process. Heroes and Lost seemed proof that even the scariest doomsday scenario would fall flat if saddled with too many subplots and secondary characters.

Do you remember those first, glorious seasons of Heroes and Lost? Both shows promised to reinvigorate the sci-fi thriller with complex, flawed characters and plots that moved freely between past, present, and future. By the middle of their second seasons, however, it was clear that neither shows’ writers knew how to successfully resolve the conflicts and mysteries introduced in the first, as the writers resorted to cheap tricks — the out-of-left-field personality reversal, the all-too-convenient coincidence, and the arbitrary let’s-kill-off-a-character plot twist — to keep the myriad plot lines afloat, alienating thousands of viewers in the process. Heroes and Lost seemed proof that even the scariest doomsday scenario would fall flat if saddled with too many subplots and secondary characters. In The Idea of History, author R. G. Collingwood argues that nineteenth-century historians viewed their task in a different spirit than their predecessors. While previous generations of scholars treated history as a simple chain of events, the Romantics wanted to recreate the past through their writings. The Romantic historian, Collingwood explained, “entered sympathetically into the actions which he described; unlike the scientist who studied nature, he did not stand over the facts as mere objects for cognition; on the contrary, he threw himself into them and felt them imaginatively as experiences of his own.”

In The Idea of History, author R. G. Collingwood argues that nineteenth-century historians viewed their task in a different spirit than their predecessors. While previous generations of scholars treated history as a simple chain of events, the Romantics wanted to recreate the past through their writings. The Romantic historian, Collingwood explained, “entered sympathetically into the actions which he described; unlike the scientist who studied nature, he did not stand over the facts as mere objects for cognition; on the contrary, he threw himself into them and felt them imaginatively as experiences of his own.”

5. Pig Bride

5. Pig Bride  4. Zone-00

4. Zone-00  3. Black Bird

3. Black Bird 2. Lucky Star

2. Lucky Star 1. Maria Holic

1. Maria Holic 10. Oishinbo a la Carte

10. Oishinbo a la Carte

4. Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka

4. Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka

I mean no disrespect to Tetsu Kariya or Akira Hanasaki when I say that the Vegetables volume of Oishinbo A la Carte irresistibly reminded me of 1970s television. Back in the day when there were only three networks, hour-long dramas doggedly followed the same formula: they dramatized a problem — say, drinking and driving, or falling in with a bad crowd — then resolved it with a little action and a lot of talking, culminating in a freeze-frame shot of the entire cast laughing at corny situational humor. Oishinbo follows this template to a tee, using hot-button issues such as bullying and pollution to preach the healing power of vegetables. The stories are as hokey and predictable as an episode of CHiPs or Little House on the Prairie, but entertaining in their sincerity.

I mean no disrespect to Tetsu Kariya or Akira Hanasaki when I say that the Vegetables volume of Oishinbo A la Carte irresistibly reminded me of 1970s television. Back in the day when there were only three networks, hour-long dramas doggedly followed the same formula: they dramatized a problem — say, drinking and driving, or falling in with a bad crowd — then resolved it with a little action and a lot of talking, culminating in a freeze-frame shot of the entire cast laughing at corny situational humor. Oishinbo follows this template to a tee, using hot-button issues such as bullying and pollution to preach the healing power of vegetables. The stories are as hokey and predictable as an episode of CHiPs or Little House on the Prairie, but entertaining in their sincerity. Seventeen-year-old Kotoko Aihara is a ditz, the kind of girl who gets easily flustered by math problems, blurts whatever she’s thinking, and burns every dish she attempts to make, be it a kettle of boiling water or beef bourguignon. Though Kotoko’s poor academic performance consigns her Class F — the so-called “dropout league” at her high school — she has her eye on Naoki Irie, the star of Class A. Rumored to be an off-the-chart genius — some peg his IQ at 180, others at 200 — Naoki is an outstanding student whose good looks and natural athletic ability make him an object of universal admiration. Kotoko finally screws up the courage to confess her feelings to him, only to be curtly dismissed; Naoki “doesn’t like stupid girls.” Furious, Kotoko resolves to forget Naoki.

Seventeen-year-old Kotoko Aihara is a ditz, the kind of girl who gets easily flustered by math problems, blurts whatever she’s thinking, and burns every dish she attempts to make, be it a kettle of boiling water or beef bourguignon. Though Kotoko’s poor academic performance consigns her Class F — the so-called “dropout league” at her high school — she has her eye on Naoki Irie, the star of Class A. Rumored to be an off-the-chart genius — some peg his IQ at 180, others at 200 — Naoki is an outstanding student whose good looks and natural athletic ability make him an object of universal admiration. Kotoko finally screws up the courage to confess her feelings to him, only to be curtly dismissed; Naoki “doesn’t like stupid girls.” Furious, Kotoko resolves to forget Naoki.