|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

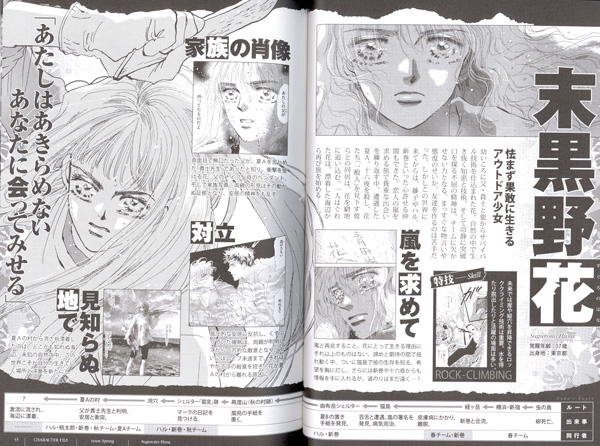

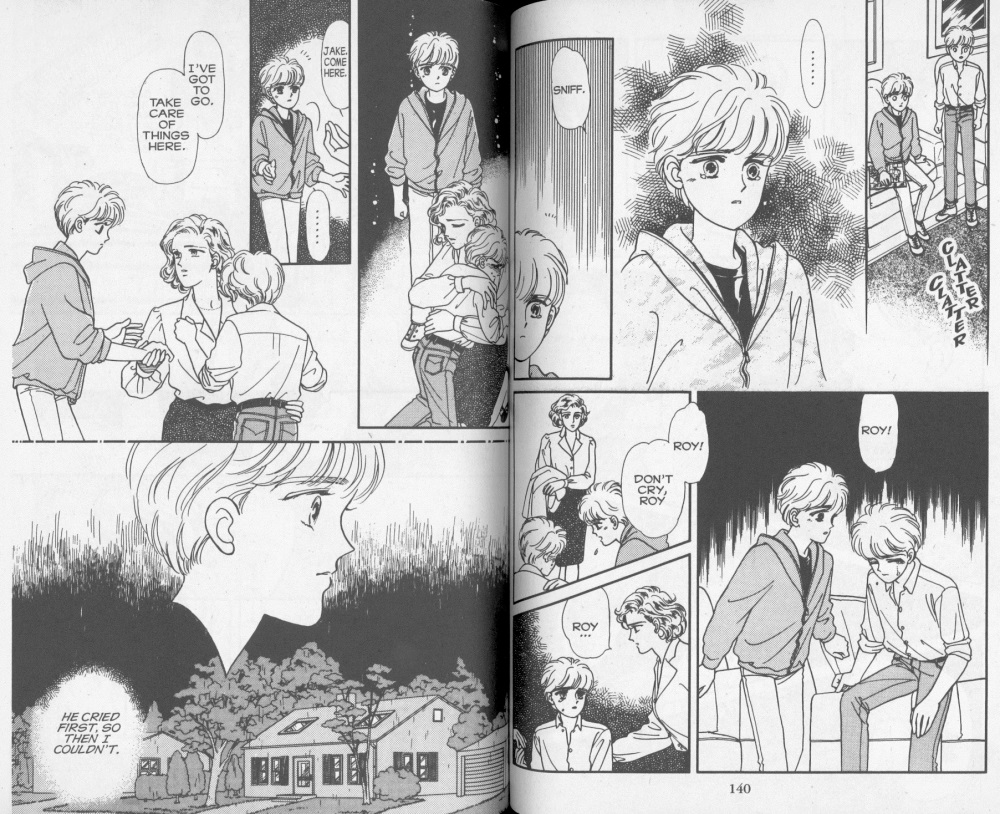

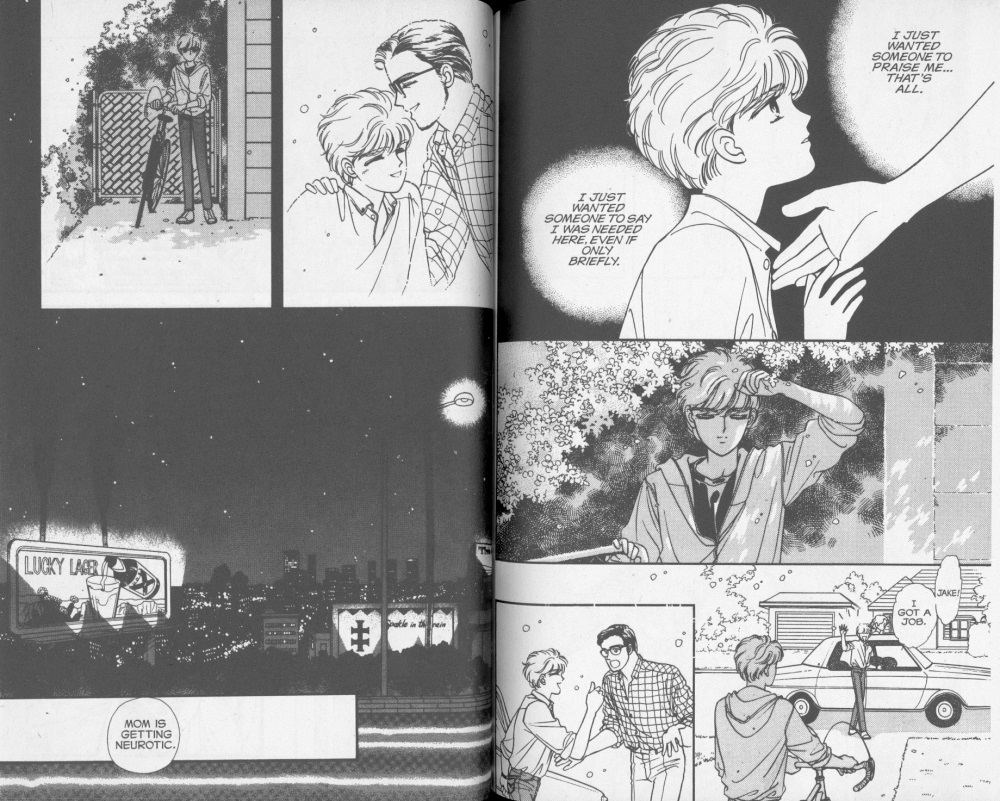

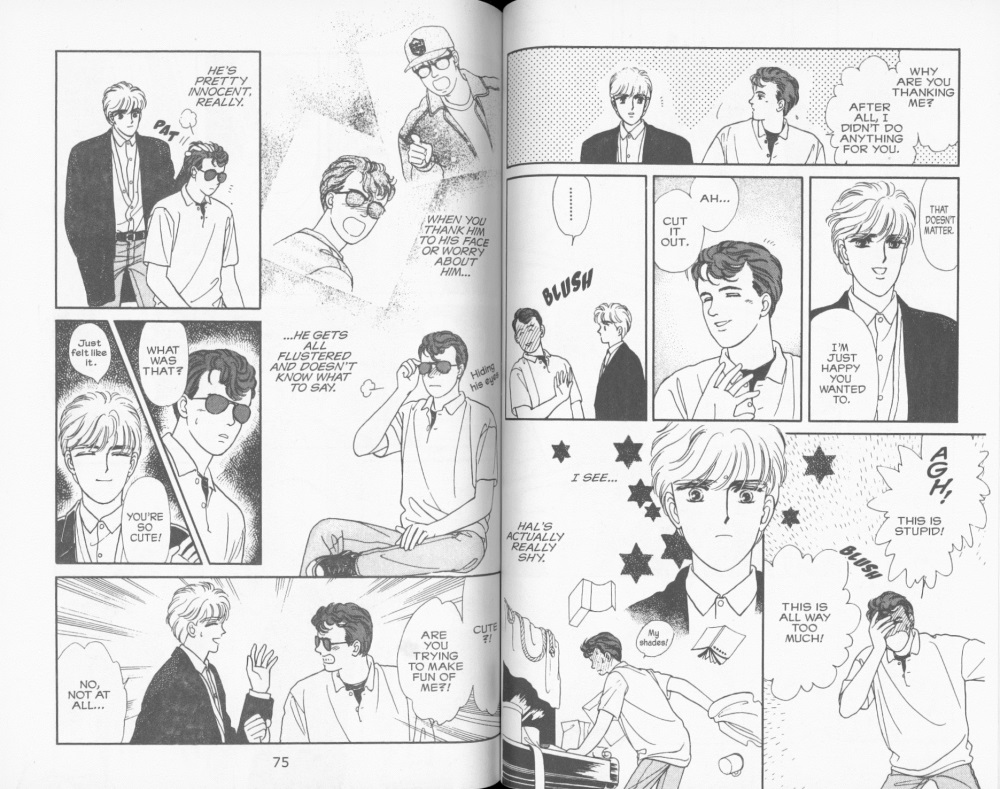

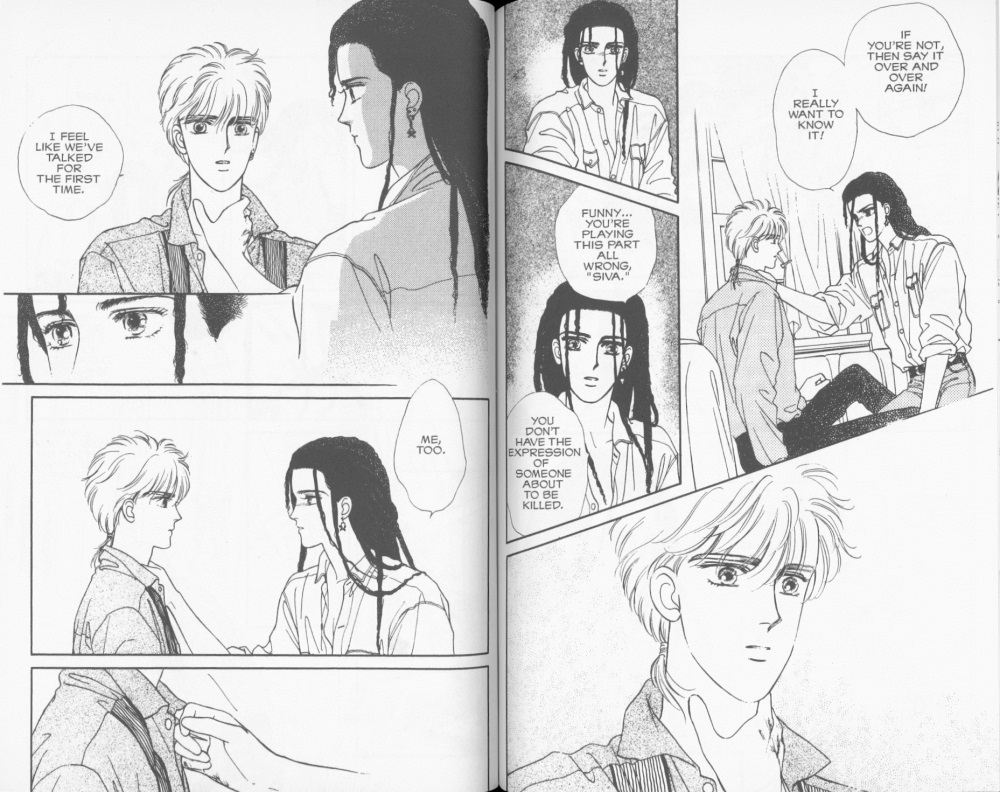

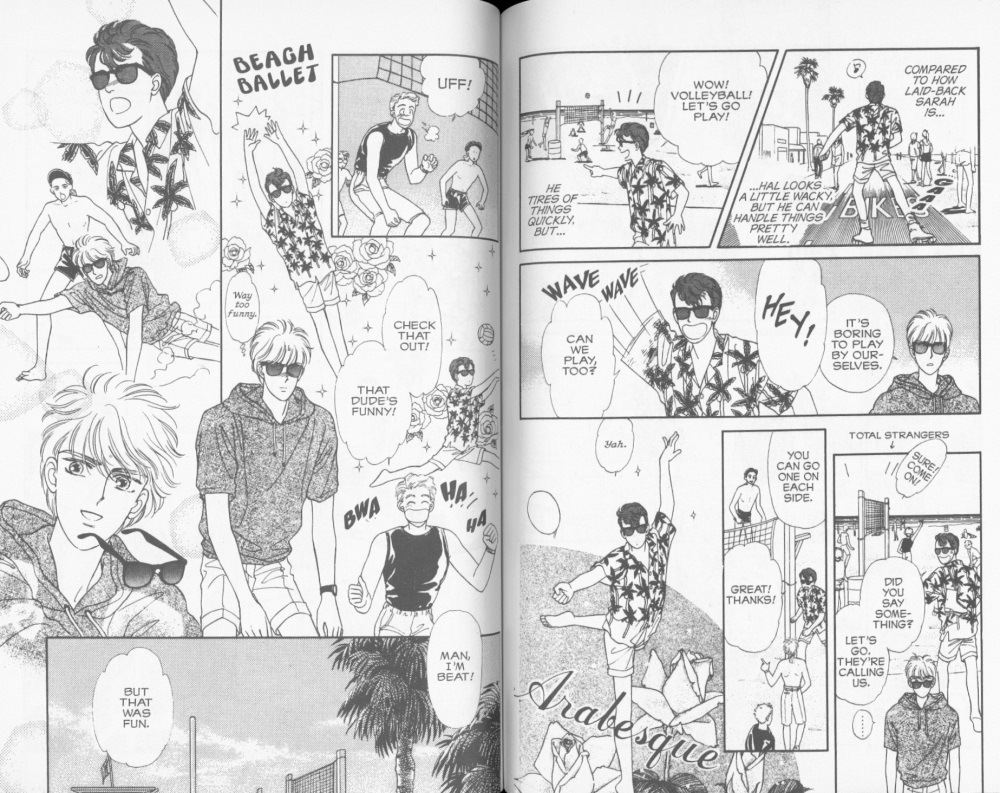

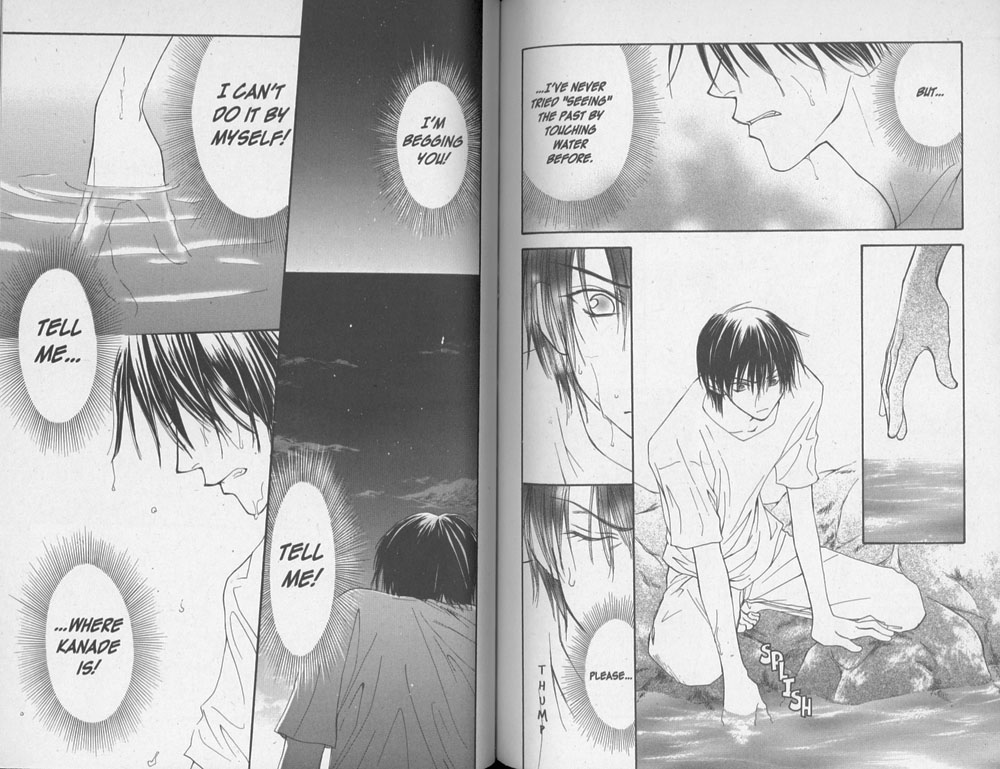

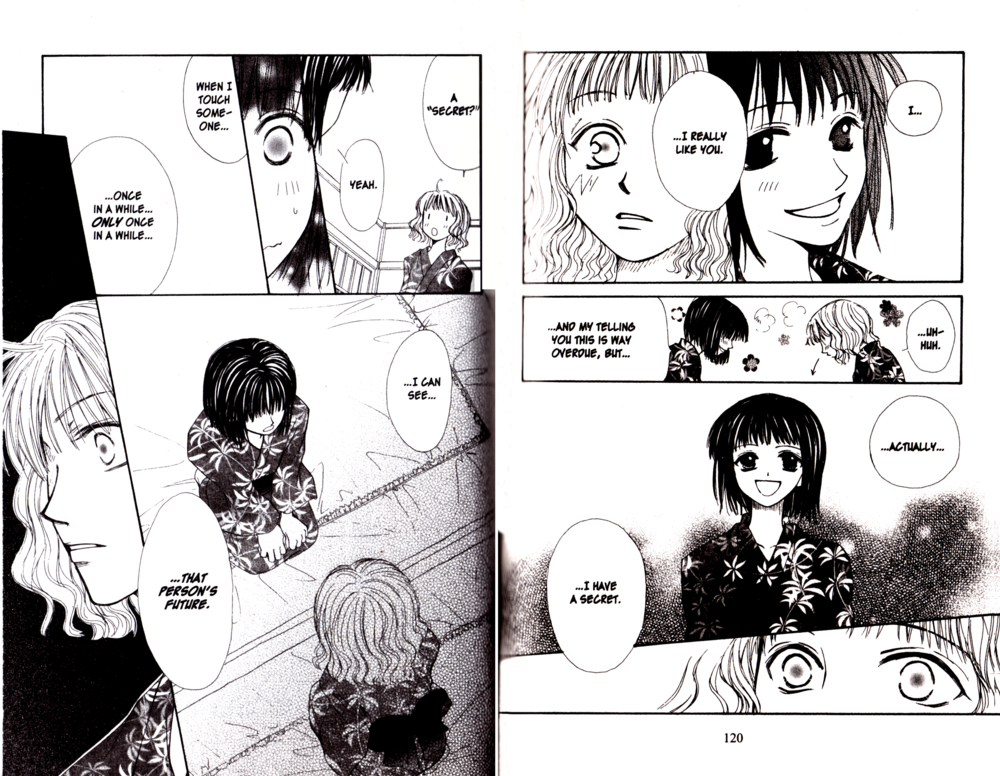

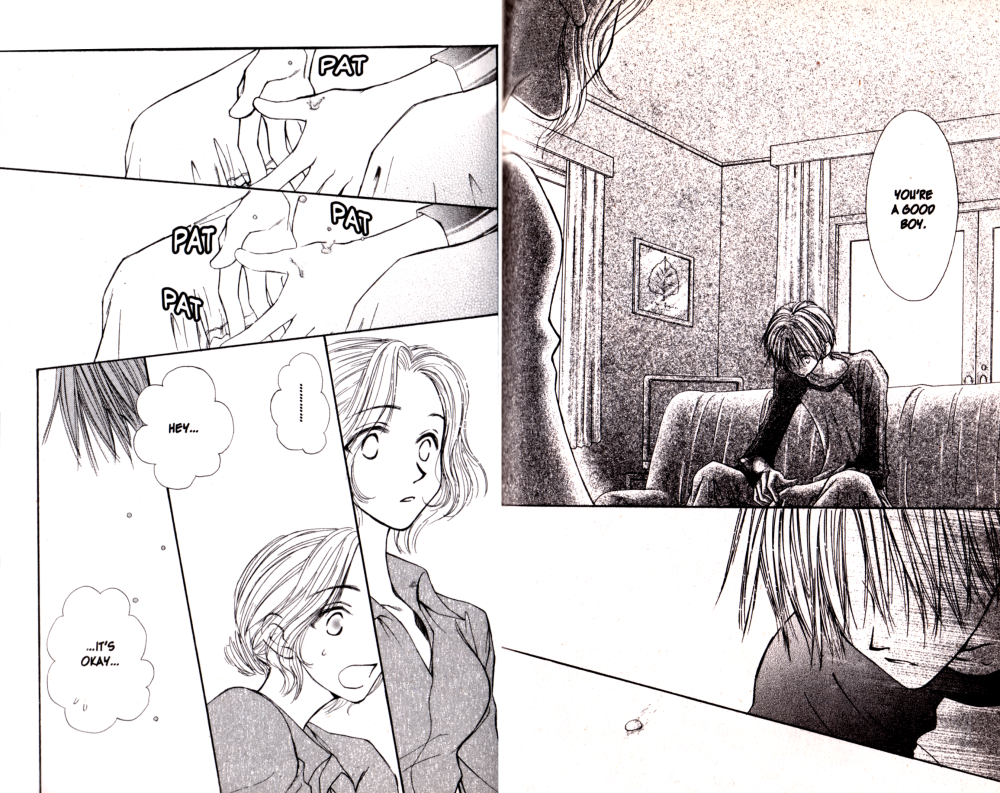

MJ: It’s time once again for the Manga Moveable Feast, this month featuring the works of Yumi Tamura and hosted at Tokyo Jupiter. Though three of her manga have been published in English by Viz Media, Tamura-sensei is best known to English-speaking fans for her 27-volume fantasy series Basara, published by Viz in its entirety between 2003 and 2008. The story—about a fifteen-year-old girl in post-apocalyptic Japan who assumes the identity of her murdered twin brother in order to free her people from the tyrannical grip of a corrupt monarchy— offers up a familiar mix of sword-fighting, military strategy, political intrigue, drama, humor, and romance along with themes less common in high fantasy, like feminism and (I’d argue) social anarchism.

Since Michelle has been a vocal fan of Basara for a long, long time, it seemed only natural that we’d dedicate this week’s Off the Shelf to a discussion of the series. We’ve also invited Anna to join in on the festivities, along with Karen Peck, Michelle’s collaborator on The CMX Project. Welcome, Anna and Karen!

Though Basara was one of the very first series recommended to me when I first began reading manga in 2007, I missed the opportunity to buy most of Viz’s editions when they were actually in print, and it took me years to acquire some of the rarer middle volumes. As a result, though I eventually did find them all, I’d only read through the first ten volumes before planning this roundtable. I suspect I’m the only one coming to the discussion as a (mostly) new reader of the series. Can you each tell me a bit about how you were first introduced to Basara?

ANNA: I think I actually stumbled across Basara fairly close to when it was first coming out. I think I picked up the first half-dozen volumes and then started buying each volume as it was released. One thing I remember was that the manga looked a bit different from the other Viz releases at the time, which definitely piqued my interest.

MICHELLE: Honestly, I’m not sure how I first encountered Basara. In my early days of manga enthusiasm, one of my goals was Buy All the Shoujo, so it’s possible I just snagged it because of its imprint. I also, however, have a distinct memory of reading about the Basara anime, thinking it sounded awesome, and acquiring some fansubs of that. I just can’t remember which came first. What I do have documented is that I read the first volume of the Basara manga in September 2004 and the last in 2008. Although merciless upon my wallet, the Buy All the Shoujo approach did save me some anguish, as I bought each volume as it came out and didn’t have to track anything down.

KAREN: I am a latecomer to Basara, having just finished reading it this weekend. I don’t know why I skipped out on it when it first came out, as I was in a similar BUY ALL THE SHOUJO mode as Michelle was. Years later, I kept hearing how awesome it was—but the idea of collecting it was daunting, as some of the volumes were out of print and fetching crazy prices online.

What really prodded me was reading 7SEEDS, Tamura’s current work, in French, which was one of the best things I’ve ever read. So I decided to go ahead and start buying up all the Basara I could, and import the French-language editions as placeholders, with the hope that prices would one day came down to something reasonable. I was lucky that a generous friend found volumes 19 through 21 for me at a used bookstore and passed them along – thanks Michelle!

MJ: So I’m not the only newcomer! That makes me happy, I admit—mainly because I found the series so exciting that I was worried my n00b squee would be so loud and obnoxious as to drown out all reasonable discussion. I mean, this thing pings pretty much everything I’ve ever loved in manga, beginning with its truly awesome heroine all the way to the simple fact of its length. Which is not to say that I love all long-running series, but I absolutely love a long-running series that is so obviously well-planned as this one was. There isn’t a single extraneous scene in Basara—absolutely everything that happens is essential to its plot line and the growth of its characters. That’s my take on it, at least. Is it just me?

MICHELLE: It isn’t just you. (But first let me express my gladness that you love this series. Maybe this is what you felt like when I was the newcomer to your beloved Fullmetal Alchemist!) Basara is incredibly well planned—though upon this reread I picked up on one subtle, possible mid-story change that I missed the first time, more on this later—and Tamura-sensei juggles the various elements with consummate skill. That’s not to say that there isn’t time for levity, for there surely is, but she’s able to combine some lighter moments with action in a way I really like. Too, there are scenes between supporting characters that are absolutely fascinating. I definitely have more to say about this later, too, but I don’t want to rush ahead before we’ve actually talked about our main characters!

MICHELLE: It isn’t just you. (But first let me express my gladness that you love this series. Maybe this is what you felt like when I was the newcomer to your beloved Fullmetal Alchemist!) Basara is incredibly well planned—though upon this reread I picked up on one subtle, possible mid-story change that I missed the first time, more on this later—and Tamura-sensei juggles the various elements with consummate skill. That’s not to say that there isn’t time for levity, for there surely is, but she’s able to combine some lighter moments with action in a way I really like. Too, there are scenes between supporting characters that are absolutely fascinating. I definitely have more to say about this later, too, but I don’t want to rush ahead before we’ve actually talked about our main characters!

KAREN: I just want to throw in my appreciation of a well-plotted series – she’s juggling a lot of balls, but she keeps the focus primarily on Sarasa and Shuri. There’s room for secondary and tertiary character development, but it never sidetracks the story. Wisely, she leaves longer stories of those characters to the extra chapters – and avoids any of those other characters from taking over in the main story. What is important is how they serve the story and relate to either Sarasa and/or Shuri – they still have their importance but they have their place, too.

I’m glad someone else will be a oh-so-excited newbie over this with me! There’s something about reading these epic series in a compressed amount of time, the drama of the story is more intense because there is no wait – having to go to sleep/work made me downright resentful, I wanted to be back in that world and see what happened.

MJ: Yes, yes, exactly, Karen! I’m a big fan of total immersion when it comes to fiction (or anything, really) and my experience with Basara was a perfect illustration of why. I read it all through in just a few days, and during that time, I really lived there. It was an awesome place to live, that’s for sure.

And that is exactly how I felt when you were the newcomer, Michelle, so I figured it would be a point of personal gratification for you! And speaking of our main characters, why don’t we jump right in? I have a lot of highfalutin thoughts regarding the series’ feminism and so on, but to get to that, we have to begin with Sarasa. Michelle, would you like to start us off?

MICHELLE: Sure!

When Sarasa and her twin brother Tatara were born, Nagi, the prophet of Byakko village, proclaimed, “This is the child of destiny.” ** The assumption was made that the prophecy would obviously pertain to the male child, and so Tatara was celebrated and fêted while Sarasa saw herself as unwanted scraps. After the Red Army attacks her village and Tatara is beheaded by General Kazan, the most loyal of the Red King’s soldiers, the people of the village are confusedly milling about. Knowing that something needs to be done to give them hope so that they might make it to safety, Sarasa transforms herself into Tatara.

She continues to live in that guise most of the time, intent on personal vengeance at first but gradually developing a desire to transform the entire country. She’s only able to be Sarasa in stolen moments with Shuri, a handsome but arrogant fellow whom she believes is a dumpling merchant but who is actually the Red King. (Hello, textbook example of dramatic irony!) Eventually, however, she does come clean about her gender to her followers, who all do not care. “You’re the leader we believe in,” they tell her.

And why believe in her? Because she’s not just idealistic about how the world should be, she acts. It’s this that earns her Shuri’s respect, too. She doesn’t just speak up about injustice, she does something about it. And not something histrionic, but typically something downright clever (though her plans are not immune to failure). One of her followers, Hijiri, puts it this way: “I think I’m starting to understand, Tatara. People don’t come worshipping you as the savior. They don’t come together under you looking for guidance… They can’t bear just to stand back and watch as you run ahead on unsteady feet, bawling your eyes out.”

** Originally, Tamura-sensei depicted Nagi as unaware of which of the children was actually the subject of the prophecy. “Now… I see what I could not,” he says. “Tatara was the sacrifice. Sarasa. You are the one…” Later, though, there’s a very small bit in volume eight where Chigusa, Sarasa’s mother, suggests that Sarasa was specifically the subject and that her parents treated her the way they did for her protection. Which basically means Tatara’s parents were setting him up to be a decoy from the start. I never caught that change the first time around.

KAREN: What I enjoyed about Sarasa is her growth – and she does make mistakes, as Michelle points out. She’s not some Child of Destiny savant, she has a lot to learn and the reader gets to see this happening. And she has to learn it while secretly coming of age as a young woman – no wonder she opens her heart to the one person who only knows Sarasa.

And as she grows, so does the revolution. Avenge her family. Rescue the sword. Each step leads to another, more challenges, more allies. Which all leads to… making a new Japan. And it turns out, as Michelle noted, the revolution was able to go on, even if it was lead by a woman – maybe it could only happen because it was led by a woman.

ANNA: I think the “Child of Destiny” aspect of Sarasa’s life is handled in a very realistic and nuanced manner. Too often, a protagonist with this type of fate ends up serving as a bit of a narrative crutch for the author. In Sarasa’s case while she is clearly destined for great things, she ends up struggling so much and sometimes being aided by random chance so that her destiny feels like it is earned through time, rather than something that was just handed to her.

Shuri, the other star-crossed lover in this equation, ends up being a great foil for Sarasa simply because he is so very different from her. He starts off as extremely arrogant and entitled, but he still cares for his people. His brutality in battle contrasts with his gentleness with Sarasa, as he doesn’t realize that she’s the leader of the rebellion.

MJ: I agree with what all of you have said, and I think what I also really appreciate about the way Sarasa is written is that regardless of whether she’s using her brother’s name or her own, she’s all Sarasa all the time. Though she clearly recognizes that as “Tatara” she has enormous responsibility on her shoulders, it’s not like the Tatara persona gives her anything she doesn’t already possess. When she eventually longs for the opportunity to just be “Sarasa,” it’s not that she isn’t able to be herself or isn’t able to be a woman when she’s calling herself Tatara. It’s that she, like any leader, occasionally longs for the chance to be selfish. She longs to be able to make decisions for her own sake only—just now and then—without having to be responsible for the lives and happiness of everyone else in Japan at the same time. She’s the girl “Sarasa” all the time, but sometimes she wishes to be only that.

Her feelings ring very true to me, and stand in stark contrast to something like Princess Knight, in which the heroine is reduced to a delicate flower anytime her “boy’s heart” is taken away from her. Sarasa couldn’t be anyone else if she tried.

MICHELLE: Very well put! This puts me in mind of a scene from the Okinawa arc in which Sarasa is dressed like Tatara, carrying his sword, and doing something heroic—trying to keep a presidential candidate from attacking a ship carrying his own brother—but all Shuri sees when he looks her way is Sarasa.

Speaking of Sarasa and her growth, one thing I really liked was that her flaws don’t go away automatically. She has a tendency to keep things from her followers, not because she doesn’t trust them but because she doesn’t want to burden them. This happens several times until Asagi (I assume we’ll have a great deal to say about him!) exploits the situation and creates the first serious discord the group experiences. Later, though, Sarasa becomes more assured when issuing commands and is able to put her comrades to use because she finally understands that contributing is important to them.

MJ: I know that Sarasa’s stubborn autonomy is one of her flaws, but I admit that it’s one I find particularly endearing—not so much when it comes to her comrades, who really need her to be willing to share her burdens, but in general as just part of her personality. People’s best and worst traits are usually flip-sides of the same thing, and Sarasa’s instinct to take care of difficult things on her own is, I think, the flip-side of her ability to take care of others when it most counts.

There’s a scene in volume five, when Sarasa and Shuri have been forced into participating in a sick “race” (actually a hunt, where humans—mostly slaves—are the hunted) for the entertainment of the Blue King, in which Shuri offers Sarasa his comfort and protection. “It’s all right. I’m here,” he says, and for a moment Sarasa thinks about how nice it must be to feel protected. “But…” she thinks, “I’m Tatara. If I were alone, I’d have to do something on my own.” At which point, she takes charge of the situation and organizes the group in building what they need to make it to the next part of the race. And y’know, she says, “I’m Tatara,” but that’s the way she is all the time. She puts herself on the front line in any situation, and that includes those that (she thinks) only affect her.

ANNA: One of the things I like about the series is how leadership is explored throughout the story. As Sarasa travels she encounters a variety of leaders in different locations as she seeks to find allies to aid her rebellion. I’m thinking of the brash style of the Pirate Queen Chacha in particular, as she provides an example of what it is like for a female to lead without disguising her gender.

MJ: Oh, I absolutely love Chacha—so much so that I wouldn’t mind at all skipping over Shuri right now and coming back to him later.

MICHELLE: That would be okay with me!

MJ: Chacha is one of those characters who grabbed me in about two seconds. I loved that fact that she was respected and revered by her crew and that there was no fuss made whatsoever about the fact that she was a woman. It was just a matter of fact.

MICHELLE: We glimpse some of her and Zaki’s shared backstory in volume seven, and even from childhood she’s challenging the notion that she won’t be able to take over leadership of the pirate crew because of her gender. She simply proceeded to get stronger than everyone, defeat them publicly, and then she was accepted. And she is definitely womanly, and passionate about her pleasures, etc.

KAREN: Chacha is indeed awesome – but there’s a number of the women of Basara I could say that about. Tamura is one of those writers who shows that women have ways to develop and display their power, in a variety of ways. Kikune, one of the Four Nobles, is the only girl in that group and feels like she has to work harder to measure up – even when she has skills beyond the others and her gender helps her with one of her assignments (such as being a lady-in-waiting to the Purple Queen). Despite her ties to the White King, she seems to be able to be helpful wherever needed – and provides Sarasa a friend her own age.

Then there’s women such as Princess Senju, Shido’s (briefly) wife and later widow, who represents the letting go of the cycle of vengeance that could undermine everything that Tatara is fighting for. Another woman who breaks that cycle is Sarasa’s mother, who devotes herself to tending the wounded of either side of the battlefield, which seems to lead to a larger “Nightingale” movement, which is significant to the healing of a united Japan as well.

MICHELLE: Definitely an impressive list! I’m also fond of Yuna, Dr. Basho’s apprentice, who becomes Shuri’s friend yet doesn’t take any of his crap and talks plainly to him, which is what he needs.

MJ: Since we’re talking about female characters, I can’t help but bring up Tara, a character who appears in one of the many side stories that populate the series’ last couple of volumes. She’s someone we eventually find out is sort of an ancestor to Sarasa, philosophically speaking—and in more ways than one! She’s living a nomadic warrior lifestyle with three men, one of whom she’s very close to (and probably in love with, but that’s a whole other thing). At one point, she’s confronted by the girlfriend of that guy who tries to appeal to her as a woman, “Please… give him back. You’re a woman, too. You must understand. A woman is happiest with the one she loves, having his children, having a family. I hope you can find that life, too.” Tara answers, absolutely befuddled, “I don’t understand. Even an animal can do that. I want to do something only I can do.”

Tamura spends a lot of time rejecting traditional ideas about what it means to be a woman, but I think even more than that, what it means to be a person. She treasures the individuality and autonomy of her characters more than anything else, but not in a self-obsessed Ayn Rand kind of way. Rather, she seems to place the greatest value on an individual’s capacity for unbridled compassion—an ability to do great things in the service of others.

ANNA: I agree, Sarasa starts out as a decent human being and manages to grow in both her capabilities and her compassion as she’s exposed to more people during her travels through post-apocalyptic Japan.

MJ: To bring this back to your discussion of leadership, Anna, one way in which Sarasa grows especially is in her ability as a leader, and it’s this that really caused me to identify Basara as a social anarchist narrative. Sarasa becomes more skilled as a warrior and as a military strategist as the story goes on, and she certainly learns the importance of trusting her comrades. But the place that trust eventually comes from—and what Tamura characterizes as her greatest strength as a leader—is in her ability to take her own ego entirely out of the equation. It’s stated several times throughout the story that the rebellion wouldn’t end if Tatara were to die, because each of Tatara’s followers is personally driven and capable of continuing the fight on his or her own. Sarasa’s a natural leader, and she’s used those skills along with the legend of “the child of destiny” to empower people to rise up against their oppressors, but the secret to her success is in knowing when not to lead—or perhaps in the fact that she leads by example rather than by rule. “Tatara’s army is a marvel,” someone observes late in the series. “Each man moves at his own discretion, but they don’t fragment into chaos.”

And while there is certainly a sense throughout the series that Tamura believes this kind of vision could only have been realized because “Tatara” is a woman, I think the message goes beyond feminism. It’s significant to me that though Tamura portrays certain forms of government in a more positive light than others, Sarasa never tries to establish any government at all. And when, in a later side story, we hear more about the government that did spring up after the rebellion, it’s already begun to sink into corruption.

MICHELLE: I actually have some geekbumps now, thinking of the first time “Tatara” specifically addresses the masses about the type of world she wants to create. It comes during volume thirteen when Renko (another strong woman!) is being persecuted for operating a newspaper critical of Momonoi, the governor of Suo City who’s been appointed by King Ukon in the Red King’s absence. In a very stirring scene, Tatara cinematically stands upon a rooftop and, for the first time, specifically orates about her vision for the future. Killing Momonoi is not the way, she insists, because a new leader will only be appointed in his place and nothing will change.

MJ: And perhaps this is the time to finally come back to Shuri, the Red King, because though Sarasa grows immensely throughout the series, it’s Shuri whose entire worldview must be torn down and rebuilt from scratch.

Our first glimpse of the Red King is as the worst kind of tyrant. When a young Sarasa accidentally runs out in front of his marching army, he—just a child himself—orders her to be killed. Thanks to intervention from Ageha (oh, so much to say about him here at some point), Sarasa’s life is spared, but the king returns just a few years later to remove the potential threat of “the child of destiny,” killing Tatara and pretty much wiping out Sarasa’s entire village.

Sarasa’s next encounter with him is at a remote hot spring, where she’s gone to soothe herself after suffering a wound in her escape as “Tatara.” There, Shuri’s just a guy, a bit too sure of himself, but still just a guy. Sarasa is put off by his arrogance, but after a second encounter, the two start to open up to each other—Sarasa about her plans to avenge her loved ones and Shuri about his plans to take control of his screwed-up family. On one hand, it’s set up as a classic tale of star-crossed lovers, but what Tamura really uses this for is to allow Sarasa to reach Shuri and introduce him to a new way of thinking without her blind hatred for the Red King getting in the way. And while this ultimately forces Sarasa to confront her own hatred, it’s Shuri whose ideas must be completely transformed, not only to be worthy of Sarasa, but also to become worthy of the people of Japan.

I’ll be the first to admit that I really disliked Shuri in those early scenes in the hot springs, and I worried initially that he was going to be just another controlling shoujo love interest I’d be expected to adore. Fortunately, that wasn’t Tamura’s agenda in the slightest.

ANNA: Shuri really changes and evolves. It is a tricky thing to pull off, showing someone so unsympathetic at the beginning only to be completely transformed through their experiences, but Tamura pulls it off. And just as Sarasa manages to surround herself with loyal followers Shuri gradually puts together his own supporters as well.

MICHELLE: Like Sarasa’s, Shuri’s evolution is so well done because it’s hard-earned and gradual. His first chance to spend some significant time with Sarasa occurs when they travel to Seiran (home of the Blue King) together, each secretly thinking to use the other as cover. They end up participating in the sick race MJ mentioned earlier, and during it, they have their first clash about how to treat people. Though Shuri dismissed her views at the time, Sarasa’s words come back to him later, even though he is still unable to admit he’s made any mistakes.

And even after he’s seen Okinawa and been inspired, Shuri really only sees the flaws in Japan and how it could be different, but still nothing wrong about himself or anything he’s done. There’s a telling scene in volume nine where he’s talking about being reborn and one starts to expect some kind of big turning point… except on the next page he reveals that instead of being a king, he’s decided to become an absolute dictator.

It’s clear that while some new thoughts are beginning to percolate in his brain, he still doesn’t truly get it. And really, his overall goals—a united Japan that is peaceful, prosperous, and green—aren’t so very different from Tatara’s. It’s just that his own ego is FULLY in the equation. Dominating the equation, in fact.

ANNA: Shuri’s arrogance is a defining characteristic. I’ve often thought that if he were transplanted into the current times, he’d be an effective CEO of a company. While he has more than enough ego to spare, he also has an uncanny ability to find people who will be loyal to him, and he uses their abilities to further his goals. In addition, Shuri’s confidence may contribute to him being a bit reckless, but his recklessness often leads to success as he often exhibits a certain kind of calculated ruthlessness when making his decisions. It is easy to see how other people would be drawn to him, because his potential for greatness is obvious.

KAREN: Shuri’s growth was exciting to watch because despite its harshness, it really, really took a long time for him to really and truly change. Where Sarasa was The Child of Destiny who was meant to change the world, Shuri really had to overcome his birthright and his destiny to become a better person, and worthy of Sarasa. But wow, how he was broken – his best friend dead, his capital burnt, deposed, forced into death race, sold into slavery – he’s hard to break and even harder to change. The reader roots for him to be a better person because there are glimpses and glimmers of a better person underneath, and what all of that intelligence and charisma could do, if used for good. The relationship between simply Shuri and simply Sarasa was important not just for the sake of romance, but to show a different side to the rebel leader and the Red King.

KAREN: Shuri’s growth was exciting to watch because despite its harshness, it really, really took a long time for him to really and truly change. Where Sarasa was The Child of Destiny who was meant to change the world, Shuri really had to overcome his birthright and his destiny to become a better person, and worthy of Sarasa. But wow, how he was broken – his best friend dead, his capital burnt, deposed, forced into death race, sold into slavery – he’s hard to break and even harder to change. The reader roots for him to be a better person because there are glimpses and glimmers of a better person underneath, and what all of that intelligence and charisma could do, if used for good. The relationship between simply Shuri and simply Sarasa was important not just for the sake of romance, but to show a different side to the rebel leader and the Red King.

Sarasa and Shuri really have to learn to trust others – Sarasa’s worry is that she’s burdening others, a trait probably having to do with feeling like the left-behind sister of the Child of Destiny – while Shuri’s is a matter of pride. He is the son of the king, he is the Red King – as Michelle, said, ego – he clings to that to a point where it could have destroyed him. When he’s deposed and the common folk try to offer their help, he angrily brushes it aside. For this reason I enjoyed seeing his friendships with Nakijin and Yuna develop, although the Shuri/Nakijin bromance wasn’t the most intense one in the series (I would give the Cipher award for Best Bromance to Nachi and Hijiri, although I’m open to other nominations).

Now that we’re into Shuri, how about the other two major players from the royal family – the mercurial Asagi/Blue King and the scheming, deeply damaged Ginko/White King?

MJ: Oh, Asagi… Asagi. I e-mailed Michelle partway through the series to express my surprise that Tamura had made me half-fall for a character like Asagi. Then later, I fell the rest of the way. Kinda pathetic, really, but wow did I find him relatable later on. You could boil his entire character down to the one simple desire: to have someone—anyone—just one person love him best. And seriously, who can’t relate to that?

MICHELLE: I love the notion of Asagi as parasite—that’s the name of the chapter in which he first comes aboard Tatara’s ship, even—because he’s so cold and calculating yet really depends on others more than anyone. At first, his presence among Tatara’s followers really stressed me out because I just hated watching everyone being controlled by him so easily, but once Sarasa gains confidence as a leader she’s able to shut down some of his schemes and manages him more effectively. Of course, by this time he’s begun to be changed by proximity to her, as was the White King’s concern.

MICHELLE: I love the notion of Asagi as parasite—that’s the name of the chapter in which he first comes aboard Tatara’s ship, even—because he’s so cold and calculating yet really depends on others more than anyone. At first, his presence among Tatara’s followers really stressed me out because I just hated watching everyone being controlled by him so easily, but once Sarasa gains confidence as a leader she’s able to shut down some of his schemes and manages him more effectively. Of course, by this time he’s begun to be changed by proximity to her, as was the White King’s concern.

ANNA: Asagi is a fully realized character, but he’s also a bit of a plot contrivance, just because he actively prevents Sarasa and Shuri from finding out the truth about each other.

MJ: It’s interesting that you say that, Anna, because that idea hadn’t really crossed my mind at all. I mean, yes, he deliberately withholds the truth from both of them after he’s figured it out, but his motivations make so much sense, it hadn’t occurred to me to think of him as a contrivance. He’s so jealous of Shuri, and has been for so long (for very relatable reasons, if not good ones) that it seems perfectly natural to me that he’d cling to any power he had (or could imagine he had) over Shuri’s life. And in the end, he really has none at all. Meanwhile, the meaningful friendship he develops with Sarasa (despite his protestations) is one of my favorite relationships in the series.

KAREN: There were certain points with Asagi where I wish he’d grow a mustache so he’d have something to twirl as he plots away. Okay, he wasn’t ever that cartoonish, but he seemed very impressed with his own scheming – he did learn from a master, after all. But he never could quite have the White King’s detachment – and this proves to be his undoing to furthering her plots. Despite all his plans, he liked Sarasa and her group – those friendships humanized him more than he ever intended. He may be selfish, but he’s very salvageable – he thankfully never got as twisted as his mentor/mother/sister. Parasites can sometimes be beneficial, after all.

One character I did love right away was Ageha. I think he has other fans here as well?

MJ: It’s difficult for me to imagine any reader not loving Ageha. He makes an immediate impression by standing up to the Red King on Sarasa’s behalf, and things only go uphill from there. He’s a rare kind of heroic shoujo figure who can spend a major portion of his time crossdressing for a living, and still strike fear into the heart of… well, really anyone. There’s a scene at one point late in the series, when Ageha has become a source of terror for those in King Ukon’s circles, and he passes Shuri on the street, dressed as a woman, strumming lightly on a small stringed instrument. And it’s one of the most menacing things in the world. Only Ageha could pull that off—both the grace of it and the foreboding.

He’s also one of the series’ most sympathetic characters, and the most tragic from my point of view. I couldn’t help half-shipping him with Sarasa, just because he was so entirely worthy of her, unlike any other man in the series, really. And I honestly cried when he sat to have a smoke with the severed head of his dear friend, Taro, who had been executed for being a journalist.

ANNA: Ageha is so larger than life and fascinating! He’s one of my favorite supporting characters in manga of all time. In addition to Basara, I would have happily read a 20+ volume series just about him. I think with Ageha as an example, Sarasa starts to get a sense of how important Tatara is as a symbol, and her use of theatricality in addition to military tactics helps her win confrontations. Ageha is in many ways the perfect mentor, showing up just when Sarasa needs him, and disappearing when it seems like she might rely on him too much.

MICHELLE: I love Ageha very, very much. One thing I was particularly struck by this reread is how he initially keeps some distance in his relationship with Tatara and still acts friendly with some of the people she opposes. It’s not emblazoned brightly, but Tamura does show this how this came to be in a conversation Ageha has with Senju in volume nine. Senju asks, “So now whose side are you on?” Ageha replies, “Now? I can’t say.” His thoughts continue with, “I haven’t heard from Tatara yet. What kind of country do you want to build? How will you change things? I still haven’t heard…”

When Sarasa returns from Okinawa, inspired, she addresses her followers with specific goals for the country’s future for the first time. Ageha looks on, impressed, and from then on suddenly becomes a much more committed ally. Has he chosen his side at last? He’s there for her in a huge way all throughout the Abashiri Prison arc—we must talk about this, which boasts several very painful scenes—and one eventually comes to realize that he’s been hoping this whole time. Hoping she was the one who’d change things, and helping her in any way he could, but maintaining some distance just in case she ended up a disappointment.

MJ: He also manages to be respected by pretty much everyone, including those who oppose Tatara the most. Besides his complicated history with Shuri’s most trusted ally, Shido, one scene that also springs to mind is in the Blue King’s castle, where he’s able to speak plainly, insulting the Blue King (the fake one, not Asagi—that’s a whole thing) who is begging Ageha to become his personal entertainer and somehow getting away with it—in part thanks to Asagi’s intervention, but also just because that’s who Ageha is. He’s not someone who can be dismissed, even in anger.

MICHELLE: I did wonder how he got to be so influential. Perhaps it’s due to his career as Kicho, which allowed him access to people in positions of power, who he was then able to charm with his beguiling dance.

MICHELLE: I did wonder how he got to be so influential. Perhaps it’s due to his career as Kicho, which allowed him access to people in positions of power, who he was then able to charm with his beguiling dance.

MJ: I think that’s got to be a major factor—much is made of the fact that he is beguiling to everyone—and I also think it’s his presence. As a former slave, Ageha went through a lot to recover himself as a person (with the help of the troupe that took him in), and as a result, I think he’s more certain of who he is and who other people really are than anyone else in the story. That alone is a real source of power.

MICHELLE: I can see that. Hence the lack of kowtowing to authority figures.

KAREN: Michelle, I wondered that too! He must be a great dancer.

I loved him most when he took a despondent Sarasa, who was heartbroken over finding out that Shuri was the Red King, away from her supportive cocoon (which also has some less-than-supportive elements) to try to make her deal with everything. I think only Ageha could have done that; she knows that he’s been through much, much worse and I think he’s the one who loves her enough to essentially abandon her when she needs it.

And then he cuts his hair. That devastated me, because his support seemed to be the most important – he seemed to be the only one that got Sarasa and the rebel leader Tarata.

I wondered at that point if he had really given up on her being “the one”. His destiny – that he would one day meet a woman worth dying for – is even heavier than Sarasa’s. Did he know when he sacrificed his eye for her when she was a child? Then he’s in Kyoto, and is it Taro’s death that drives him to his endgame? Or is he realizing, like Sarasa, that he can’t outrun his destiny?

MJ: I love that you brought all this up, Karen, and especially the cutting of his hair, because it seemed so… final. I’m grateful that it wasn’t, and that he came back to Sarasa in the end, but his story is the most painful for me, ultimately, because I have the same questions as you do, and I wonder if he was really sure, even in the end, that she was that “woman worth dying for.”

ANNA: Ageha’s status as a person apart also serves as a contrast to the familial bonds that develop between Sarasa and her companions. It is easy to see that Ageha has plenty of friends, but something about him always remains solitary.

MJ: You know, Anna, I think maybe that’s why the scene where he brings a smoke for Taro’s severed head affected me so strongly. It’s such an intimate moment, really, even though Taro’s gone. We don’t see Ageha showing that kind of personal vulnerability that often.

ANNA: He isn’t often shown that vulnerable, although he does seem to have an immense capacity to endure suffering in addition to his almost super-human personal magnetism. I think it all contributes to his mystique and the way everyone around Ageha responds to him as a larger than life character.

MICHELLE: This reminds me of something he thinks while incarcerated at Abashiri Prison. In order to protect Sarasa, he gives his body to the leader of the cell in which they’re placed. Sarasa is absolutely anguished about this. Ageha tells her to close her eyes and cover her ears, and then narrates, “From birth.. my tarot has been the “hanged man.” It is the card of sacrifice, ordeals, and unrequited love. Yeah, it’s dull. But you know what? You are worth it.”

MJ: Even with all that tremendous mystique, I’ll admit that Ageha’s strong presence in Sarasa’s life actually came as a bit of a surprise to me. It’s Nagi who is the most influential early on, and it’s not that he’s exactly replaced by Ageha, but somehow Ageha comes to understand Sarasa the most thoroughly. In fact, the only person who I think comes close to the same level of understanding is Sarasa’s mother, who isn’t even with her for the bulk of the series.

I have a favorite scene between Sarasa’s mother and Shuri, in which she’s clearly figured out who Shuri is and tells him about her daughter. And it’s amazing how well she knows Sarasa, even though they’ve been separated for so long and though it seemed that Tatara was the focus of their parents’ attention before that. Her honest assessment of Sarasa in that scene reminds me of Ageha somehow, as though Ageha is in some way fulfilling her role in Sarasa’s life in her absence.

Well, her role, but with more killing. And maiming. Much more maiming.

MICHELLE: Sarasa does liken him to a parent at one point!

ANNA: I feel like the discussion of maiming is a good jumping off point to discuss the great action scenes and set pieces in Basara. One of the reasons why I enjoy this series so much is because it invests a ton of emotion in action scenes.

MICHELLE: You’re so right, Anna. What springs to mind immediately is the incredibly intense battle in volume three between Chacha’s crew and the Red King’s forces, who appear to have them surrounded. A desperate yet determined Sarasa stealthily swims through the king’s fleet (using a shark for camouflage at one point), boards a third party’s ship, and then uses their cannon to blow the fleet to smithereens. This is all very exciting, and a huge victory for Tatara, but amidst the carnage, Sarasa spots the silhouettes of soldiers suffering and dying in flames. “Those are red demons,” she tries telling herself. “The red demons that destroyed my village.” But that doesn’t stop her tears from flowing, and from this point on, she’s always cognizant that even her enemies have loved ones that will mourn their passing.

MJ: That’s one of my favorite battle scenes as well, Michelle. Another pretty spectacular sea battle is later in volume nineteen, in which Tatara’s army has reached such a desperate point that they have no choice but to blow up their own ship—one which has become home to so many of their people. It’s an incredibly tense battle, involving enemy armies and a group of assassins who have been sent to kill Tatara. I’m not always big on manga battles, because I often find them difficult to follow, but even with so much going on, Tamura leads us through so expertly. As a result, it’s both exciting and extremely moving on a number of levels. The sinking of the Suzaku flagship feels both tragic and somehow freeing—like it was one last comfort necessary to cast off in order for Tatara’s comrades to be free.

ANNA: I think Tamura always does a great job at making the battles emotionally meaningful and a demonstration of character development. Sarasa learns with each confrontation, and how people fight tells the reader something essential about their personalities.

MJ: At first when you brought up the action scenes in particular, Anna, I thought I would have trouble coming up with favorites, because I’m such an emotionally-driven reader. But as you say, the battles in Basara are so emotionally meaningful, they are really completely essential to my experience with the series and so many of the things about it I hold dear.

Do you have a favorite scene of your own? Or a favorite set piece?

ANNA: There are so many great action scenes that the favorites that come to mind are likely to just be centered around whatever volumes I’ve read recently. That being said, I think the scenes when Sarasa is trapped in prison in volumes 11-12 are particularly harrowing and claustrophobic. I’ve just finished rereading volumes 13-16, and the battle in volume 14 where Sarasa and Shuri confront each other as Tatara and the Red King is particularly devastating emotionally. You can see them work through the psychological blocks they inadvertantly inacted about each other’s identity, and they are both just utterly destroyed by their new knowledge finding out that the person they love is their hated enemy. Seeing Sarasa slip into a fugue state as she forces out the commands to kill the Red King made me wonder if this was a blow she’d be able to recover from.

Also, my favorite action scenes would also be anything featuring Ageha, since he is so fabulous.

KAREN: Tamura has the sort of art that works so well for action scenes – its very fluid and lively, but she still manages to make it all personal. These are the characters we’ve grown to care about, after all. The action scene in particular that stands out to me is the battle where Sarasa and Shuri realize who the other is – the battle is rising and then there’s this stunning, shattering confrontation in the middle of it. So much action, but there’s an amazing, emotional heart to it all.

MJ: Anna and Karen, I’m so glad you brought that particular scene up, because I thought of it as well, and I just wasn’t sure how to talk about it. Because what’s so stunning about it is that confrontation you mention—the sudden inaction in the middle of all this action. Everything comes to a complete halt, with the on-screen action matching perfectly the emotional state of the two leads. There, in the midst of their passionate rage, they see each other and their worlds just… stop.

This is something we encounter often in romantic fiction, where two lovers (or soon-to-be lovers) spot each other across a crowded room and their hearts stop and everything else suddenly falls away. Except that convention is nearly always used to illustrate something wonderful—that heart-stopping recognition of true love, the spontaneous creation of a slow-motion universe of two. But in this case, Tamura does something very similar to illustrate two hearts shattering to pieces over that recognition. Everything else falls away, but the universe they’re left with—that universe of two—is the worst thing they can imagine.

MICHELLE: One thing I especially love about the way Tamura has structured her story is that we are privy to how painful this is for both of them. It’s not just the heroine realizing that the one she loves is her enemy, who has dealt her many personal blows. She has also dealt him many personal blows, killing Shido and putting the final nail in the coffin for Suo, the city he and Shido planned together and loved so much.

MJ: Well said, Michelle! I was thinking in particular about that scene that I really appreciated that they were *both* completely ruined by the realization of who they really were. I half expected one of them to attack anyway—to be enraged by the revelation rather than ruined. That they both broke down so completely not only felt entirely refreshing, but it also added depth to the love scene earlier in the volume. It made it clear that their love was real to both of them, and not something that even hate could overcome.

ANNA: I also loved the aftermath of the scene where Asagi is saving Shuri for further torment and he becomes more and more frustrated with Shuri’s utter indifference to him. It was a small moment of comedy after some very emotional events.

MICHELLE: Tamura is positively wonderful at including small moments of levity amidst serious goings-on! I adore the little background reunions between Kagero (Ageha’s owl) and his son, Shinbashi, every time their two humans meet up, for example.

MICHELLE: Tamura is positively wonderful at including small moments of levity amidst serious goings-on! I adore the little background reunions between Kagero (Ageha’s owl) and his son, Shinbashi, every time their two humans meet up, for example.

And there’s another memorable gag in volume fourteen right in the middle of Nachi’s tense espionage mission. Not only is he attempting to recover someone’s body so that he may be buried alongside the woman he loved, but he’s also been tasked with sabotaging the palace’s well. While skulking about he comes across Nakijin, Shuri’s Okinawan ally, and they both immediately are stricken by the resemblance of the other’s hair to a pineapple. This is funny enough on its own, but it happens again in a few pages and still elicits giggles.

I also love the sidebar profile for King Ukon where someone off-panel is hurling a rock at him. I think Tamura-sensei and I must be on the same wavelength, humor-wise.

ANNA: I think the little flashes of humor is one thing that keeps the series from seeming long or tedious, even though it stretches across many volumes.

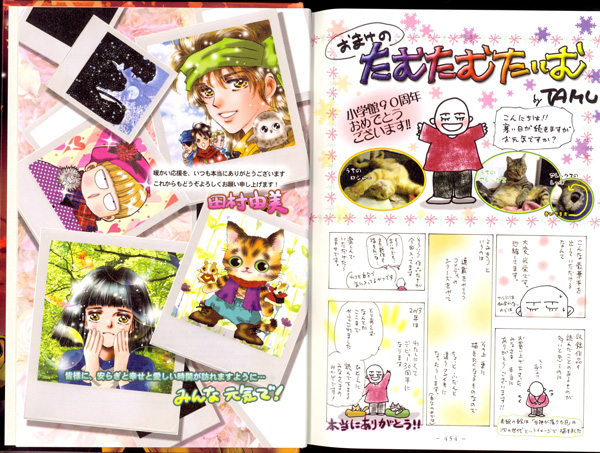

KAREN: I really like Shinbashi – and sometimes his bits are taking place in the background, as if Shinbashi is having his own epic adventure as well. Tamura also does some great side-panels and her “Tam-Tam Time” is really wacky stuff. The extra gag stories are also worth reading – she clearly loves her characters but also loves to mess with them – the high-school and singing contest re-imaginations were a lot of fun.

The other running gag I liked was Shuri’s “bird mouth” moments, which his daughter seems to have inherited.

MJ: I’ll admit that I often skip gag strips in series like these, because I’m usually anxious to get to the next volume and I hardly ever find them funny anyway. But like Hiromu Arakawa (again? I really didn’t expect Fullmetal Alchemist to come up at all in this roundtable, let alone twice—heh) Yumi Tamura is actually funny.

KAREN: MJ, I got a very Hiromu Arakawa vibe in her off-story panels/pages as well. I tended not to skip because unlike other extra stories, I needed the palate-cleanser of offbeat humor some of the dramatic and heart-breaking places where each volume left off.

MICHELLE: I think this may be my cue to unleash the torrent of squee I’ve been holding in: I freaking love Shinbashi SO MUCH. Even though there’s been plenty of horrible things happening since the beginning of the series, the first scene to truly make me bawl happens in volume eleven. Sarasa, Ageha, and Asagi are on their way to Abashiri Prison and when Shinbashi objects to the treatment they receive, he gets thrown out of the cart just as it’s beginning to snow. He can’t fly yet, and we get several just awful pages of Sarasa’s anguish as she pleads for the driver to stop.

Ageha attempts to bolster her spirits, but we don’t see Shinbashi again for a couple of volumes.

When we do, he can fly and has a new home. Sarasa acknowledges that it would probably be better for him to stay there, but he rejoins her and her reaction of pure unadulterated joy at his return is quite literally making me tear up right now just thinking about it.

MJ: Oh, Michelle, YES. I kind of lost my mind with grief when Shinbashi was lost in that volume, even though I felt that it was very likely we’d see him again. And his eventual reunion with Sarasa… GAH. I think you and I had very similar reactions to all of this. In general, I love that fact that Shinbashi is so much a part of everything—even in the love scene I mentioned earlier, he’s around, barely avoiding getting smushed in all the excitement. It means a lot to me that he’s so important.

MICHELLE: Me, too. I mean, in a way, it’s like he didn’t just return to/for Sarasa but chose to be part of the rebellion rather than seize his chance at a cushy life. Like Karen says, he’s having his own epic adventure, too! There’s a great page in volume fourteen too, where he’s just returned from his first solo messenger assignment, then flies back to Sarasa’s side wearing the most adorably determined expression.

ANNA: I think that Shinbashi is the most fully realized animal sidekick that I’ve seen in manga, in terms of him having a distinct personality and adding an essential layer to the story.

KAREN: Anna, I agree with you about how nice it is to have a useful animal sidekick. For communication purposes alone that’s a great contribution – like all of Sarasa’s other allies he’s very useful and, as Michelle pointed out, chose to be there.

MJ: This may sound a bit random, but you know I’ve had Harry Potter on the brain lately, and in some way having Shinbashi around, being so wonderfully written, has helped me get over my seemingly never-ending grief over the death of Hedwig. I never knew I had such a thing for owls, but there it is.

MICHELLE: You are not alone. I thought of Hedwig, too. Of course, now you’re making me ponder which characters in Basara match to which characters in Harry Potter, but while some fit, I think most probably don’t.

MJ: Ha! Well, I’ve already talked at length about Asagi and Draco Malfoy, but I hadn’t really thought further about anyone else. Well, maybe the White King as Voldemort? Though she’s a lot more sympathetic than Voldemort ever is.

MICHELLE: Hayato as Ron? Ageha as Lupin? These are just off the top of my head, but maybe. I guess Nagi and Kaku could be Dumbledore and Hagrid? Hee.

MJ: Ageha’s such a badass, maybe he’s Remus and Sirius all rolled up into one.

KAREN: off-topic, but when mentioning other fantasy franchises, every time Masunaga popped up I totally got a Lee Pace-as-Thranduil-in-The Hobbit image going on, and now I can’t shake it – I think it’s the eyebrows combined with an odd headdress that did that to me.

MJ: I love that imagery, Karen! I don’t know that I had many major fantasy references spring to mind while reading (other than what I mentioned already) though I did at one point mentally compare the fake Blue King to Joffrey Baratheon.

MICHELLE: I guess we ought to try to wrest ourselves back on to Basara itself. One question I wanted to put to the group is pretty broad… do you personally have any favorite scenes that have not been mentioned so far?

MJ: There are a thousand moments in the series proper that I love with my whole heart—too many to even sift through, really. But for some reason, my mind keeps bringing me back to one of the side stories in the final volume called “Black Story: Cherry.” It’s a bit of backstory involving Masunaga and Tamon, two of the characters we first met in the Abashiri Prison arc. Both were among four boys chosen as potential wielders of the Genbu sword—one of the four swords passed down through generations that become central to Sarasa’s quest for allies to join her rebellion.

The four are sent into ceremonial test to see which of them is worthy to inherit the sword. Masunaga is frustrated that Tamon—by far the best sword fighter among them—lacks the aggression required for a warrior, but when the get into the test, it’s only Tamon who is able to see that “foes” they are fighting are actually each other. In the end, he is given the Genbu sword, which as it turns out, is made of bamboo.

Partly, I like this story because I like gentle Tamon, who wants nothing more than to spend his days fishing. But I also like the Genbu sword as a symbol—as a warning against the thirst for blood that consumed the original sword and its wielder.

ANNA: For me really most of the scenes in volume 25 that concluded the story were incredibly effective. The last time we see Ageha, Sarasa’s final choice, all of it added up to a tremendously satisfying ending.

MICHELLE: I mentioned before about scenes between supporting characters being fascinating, and one relationship that I just could not get enough of was the one that developed between General Kazan and Chigusa, Sarasa’s mother. Shortly after Chigusa was captured (and subsequently abused by the Red King’s men), she comes under Kazan’s protection. He’s clearly in awe of her beauty and dignity, and she lives for a time as his guest, unbeknownst to the Red King. Asagi sees to it that this secret eventually comes out, and though Shuri gives Kazan several chances to claim that this apparent treachery was all a clever ruse, loyal Kazan refuses to take the offered way out, because doing so would sully his feelings for Chigusa. Chigusa is stunned. Despite what Kazan did to her son, he’s still clearly an honorable man. I just love that so much.

I’m also haunted by a particularly indelible sequence of pages at the end of volume 22, but I’m not going to spoil them!

KAREN: It’s hard to pick just one! But if I must… it would be from volume 16, where Sarasa finally meets with her mother again after so long. I’m glad that Michelle mentioned Chigusa and Kazan, I think that experience gave her some of the wisdom that she was able to use to counsel her daughter. “I can’t do it… I can’t hate anyone anymore.”

It took other people to bring Sarasa back from the shock of finding out that Shuri was the Red King – as I mentioned before, Ageha, but her mother is able to bring her some peace yet gives her permission to feel the pain she’s been carrying. Only after she lets go of the pain and guilt that she bears, Sarasa is not just functional again – she is able to articulate her vision of the Japan she’s fighting for – and she’s also able to want to see Shuri again, to see what his dreams are for Japan. It’s the first step in reconciling Shuri as the Red King, her lover and her enemy, which will all lead up to the final battle and its outcome, as we will see in volume 25. That ending couldn’t have been as satisfying and justified without the groundwork being laid – in this case, with simple acts of compassion to dying men on a frozen mountain.

MJ: Another scene that springs to mind comes near the end of the series. Tatara has brought her army into a final battle with the Red King, who appears to be fighting on behalf of the royal family. She’s been confused the entire time, though, because Shuri’s been fighting in an oddly extravagant manner—with showy effects, expensive equipment—even a freaking elephant. Finally, as the battle reaches its climax, Shuri reveals that he’s deliberately collected all the wealth and old relics of the royal regime to be destroyed in battle.

What’s spectacular to me about this scene, is that it simultaneously demonstrates Shuri’s new commitment to a different way of life for the people of Japan, while also showcasing his still-enormous pride. Shuri’s so proud of himself for pulling this off right under the noses of the aristocracy, he practically radiates it. I just love the fact that Tamura was careful not to change his personality regardless of his shift in political philosophy.

Thank you so much, Anna and Karen, for joining us in this discussion! And thank you, Michelle, for inspiring me to working to collect all these volumes. I expected to love Basara, but I’m not sure I was prepared for just how much I’d love it. I finished the last volume just a couple of weeks ago, and I’ve wanted nothing more than to start from the beginning and read it all again.

I dearly hope that Viz will be able to offer this series digitally someday soon, but I simply have to say that if you’re a manga fan, a fantasy fan, a or even just a fan of extraordinary storytelling, it’s worth trying to hunt down all 27 print volumes. It’s that good.

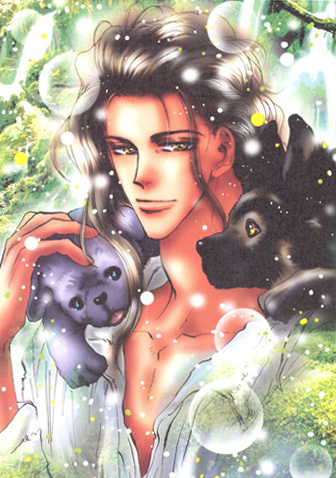

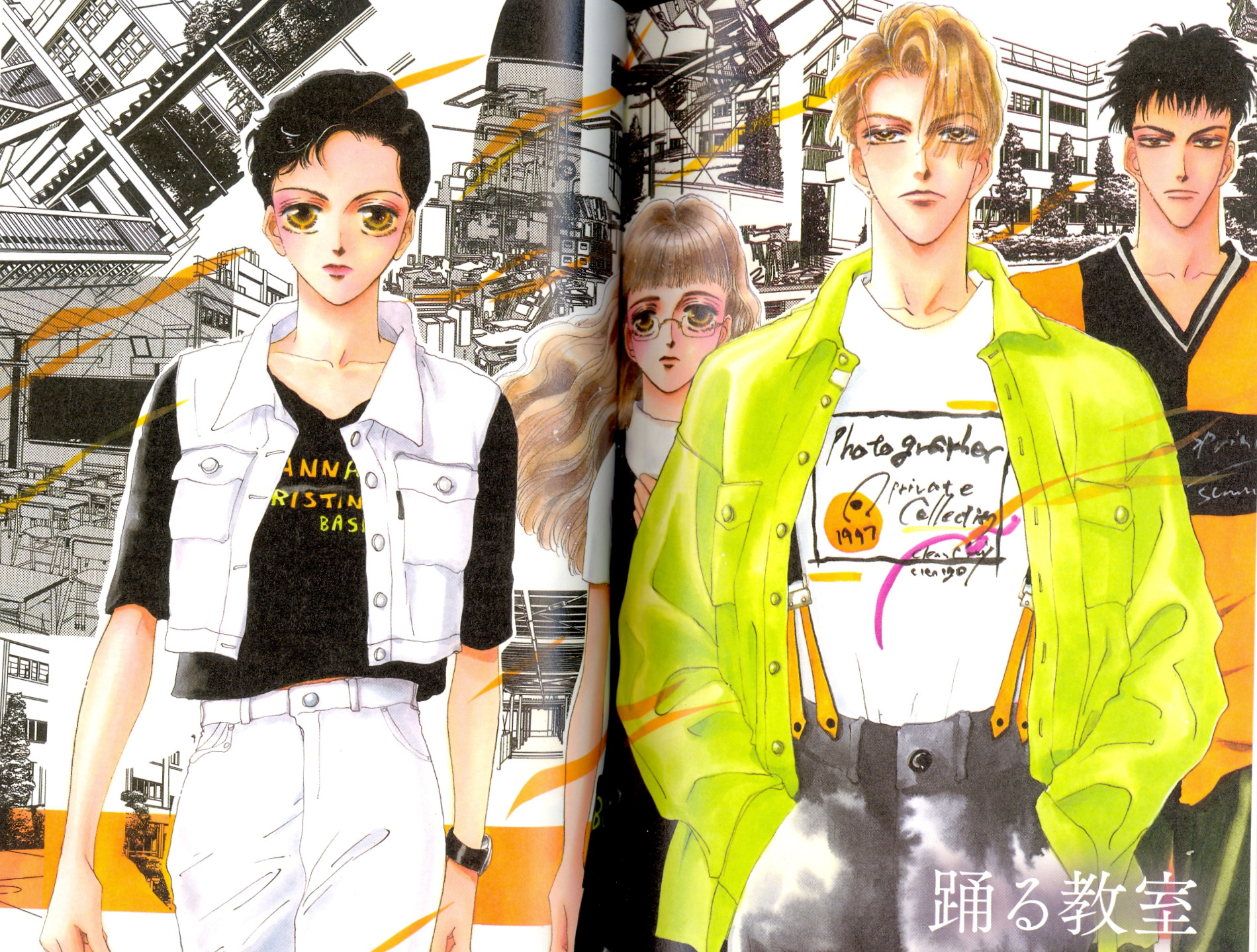

All images © Yumi Tamura/Shogakukan, Inc. New and adapted artwork and text © Viz Media. Color images from the Basara Postcard Calendar Book. This article was written for the Yumi Tamura Manga Moveable Feast. Check out Tokyo Jupiter for more!

More full-series discussions with MJ & Michelle:

The “Color of…” Trilogy | One Thousand and One Nights | Please Save My Earth

Princess Knight | Fruits Basket | Chocolat

Wild Adapter (with guest David Welsh) | Tokyo Babylon (with guest Danielle Leigh)

Full-series multi-guest roundtables: Hikaru no Go | Banana Fish | Gerard & Jacques | Flower of Life