I have a challenge for all you Shonen Jump readers: pick up a copy of Kekkaishi. It may not be as sexy as Death Note, or as goofy as One Piece, or as battle-focused as Bleach, but what it lacks in flash, it makes up in heart, humor, and good old-fashioned storytelling.

I have a challenge for all you Shonen Jump readers: pick up a copy of Kekkaishi. It may not be as sexy as Death Note, or as goofy as One Piece, or as battle-focused as Bleach, but what it lacks in flash, it makes up in heart, humor, and good old-fashioned storytelling.

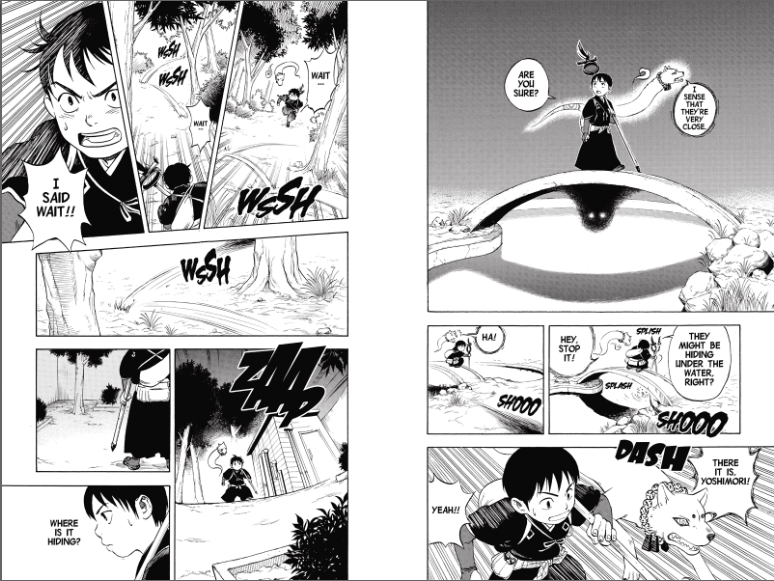

The premise of Kekkaishi is simple: Yoshimori Sumimura, a seemingly unremarkable fourteen-year-old boy, is a kekkaishi, or barrier-master. When he isn’t consuming unhealthy amounts of coffee-flavored milk, dozing off in class, or baking architecturally magnificent cakes (one of his pet obsessions), he’s patrolling the grounds of his school, which sits atop the Karasumori, a locus of magical energy that proves irresistible to ayakashi (demons) looking to augment their power. Yoshimori traps unwanted visitors within cube-shaped barriers, then vaporizes them, barrier and all.

Joining him on patrol are his sixteen-year-old neighbor Tokine Yukimura—a more disciplined kekkaishi whom Yoshimori secretly adores—and a small complement of demons that includes two dog spirits, Madarao and Hakubi, and a half-human, half-ayakashi, Gen Shishio. Further complicating matters are the families themselves: the Sumimuras and Yukimuras detest one another. Though their clans have been tasked with protecting the Karasumori for nearly 500 years, the oldest generation carries on an energetic feud, making it difficult for Yoshimori and Tokine to work together harmoniously. In short, Kekkaishi reads like an entertaining mash-up of Bleach, InuYasha, and Romeo and Juliet. (Or maybe Romeo Must Die. Take your pick.)

Each volume unfurls at a brisk clip, in part because Tanabe doesn’t feel the need to explain the entire mythology of the Karasumori site all at once. Nor does she resort to the kind of lazy, expository dialogue found in many shonen series with complicated backstories. (You know the kind: “As you know, Tokine, we’ve been combating ayakashi together for almost a year, and our faithful demon dog sidekicks have played an indispensable role in helping us rid the site of ayakashi. Don’t you think, childhood friend and neighbor of mine?”) Instead, Tanabe reveals details about the Karasumori site’s past gradually as she introduces new characters and confronts her principal cast members with new demonic challenges. In fact, the kekkaishis’ greatest adversaries—the Kokuburo, a group of powerful demons whose plan for world domination involves taking over the Karasumori site—don’t even appear in the first volume of the series.

What makes Kekkaishi such a joy to read is Yellow Tanabe’s consummate skill as both an illustrator and storyteller. Her artwork is clean and attractive, with bold lines and nicely composed pictures. Though her character designs are immensely appealing—and seem ready-made for the inevitable assortment of lunchboxes, t-shirts, shijikis, and coffee milk drinks that the series inspired—it’s her action sequences that really shine. Kekkaishi is one of the few shonen series where the fight scenes are (a) dynamic (b) thrilling (c) easy to follow (d) essential to the plot and (e) just the right length. There’s also a wonderful sense of play in Tanabe’s combat. Yoshimori and Tokine use kekkaishi not only as traps, but also as aerial stepping-stones that allow them to pursue demons mid-air.

There’s another appealing—and slyly didactic—aspect to these fight scenes as well. Though Yoshimori possesses greater spiritual powers than Tokine, it’s Tokine who frequently saves the day. Why? Because she practices creating barriers with the same diligence as she does her homework. Yoshimori, on the other hand, struggles to master his powers, sometimes embarking on marathon training sessions and other times neglecting to practice at all.

Kekkaishi offers readers more modest pleasures as well. Tanabe creates a colorful cast of supporting characters that include Yoshimori and Tokine’s sparring grandparents, who prove surprisingly spry for a couple of sexagenarians; Yoshimori’s father, who reminds me of James Dean’s apron-clad dad in Rebel Without a Cause; Masahiko Tsukijigaoka, a genial ghost who was a baker in life; Heisuke Matsudo, a nattily-dressed friend of Yoshimori’s grandfather with a specialty in weird science; and Mamezo, the grouchy guardian spirit of the Karasumori site who looks a bit like Kermit the Frog on a bender. Tanabe’s villains are a less colorful and distinctive bunch than, say, Naraku’s various incarnations, but I find that refreshing. For once the hero—and pals—are as vivid and appealing as the bad guys without having sordid or unnecessarily complicated backstories.

Like all shonen series, Kekkaishi suffers from an occasional dry spell. In volumes seven and eight, for example, the series seemed to have lost its mojo; I found the fight scenes tedious and felt Tanabe had fumbled in her depiction of Tokine, who went from being an appealing, competent character to a mere tag-along. But Tanabe quickly righted the ship in volume nine, introducing new characters, fleshing out the Kokoburo’s motives for capturing the Karasumori, staging some ecological intrigue at the Colorless Marsh, and revealing that Yoshimori’s dad has some demon-busting skills of his own. Though volume nine features two dramatic fight scenes, it’s the quieter, character-building moments that really shine, raising the emotional stakes by revealing unexpected facets of the heroes’ personalities; what happens in volume ten is all the more devastating because Tanabe makes us care deeply about her characters’ welfare.

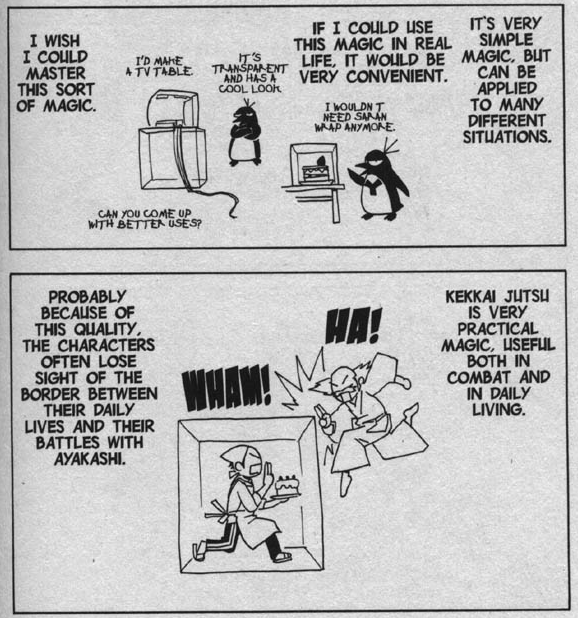

If I still haven’t persuaded you that Kekkaishi is more fun than a barrel of demon monkeys, let me sing the praises of Yellow Tanabe’s omake. I don’t usually read sidebars or gag strips for reasons that David Welsh so aptly summarized in a memorable blog entry:

The content is generally pretty repetitive. They’re working really hard, and they’re sorry they’re behind on their fan mail. This volume isn’t as good as they’d have liked, but they’re trying, and reader support keeps them going. They wish they had a kitty. That sort of thing.

Tanabe’s omake steer clear of the usual bowing and scraping before the fandom. Instead, she depicts herself as a slightly tubby penguin with a perpetual scowl and an implacable panda for an editor. Not much happens in a typical strip, but the back-and-forth between penguin and panda is amusing and, for anyone who’s ever been on the receiving end of editorial criticism, all too true. She also has a lot of fun explaining her creative decisions:

And if you’re still on the fence, let me pull out my trump card: Kekkaishi is complete. Done. Finished. Finito.

After a successful eight-year run in Weekly Shonen Sunday, the series wrapped on April 6th with the publication of its 334th chapter. And by successful, I mean successful in Japan, where the series inspired a 52-episode television series and a robust assortment of video games, and nabbed nabbed the 2007 Shogakukan Award for Best Shonen Series. Here in the US, however, Kekkaishi has barely made a ripple. VIZ has been making a concerted effort to promote the series, featuring sample chapters on its Shonen Sunday website, licensing broadcasting rights to Cartoon Network, and releasing two budget editions: one digital (for the iPad), and one print. (Look for the first three-in-one edition on May 3, 2011.) I’m not sure why Kekkaishi hasn’t caught on with American audiences yet, but now is a great time to jump into this addictive series. I dare you not to like it!

This is a revised version of an essay that originally appeared at PopCultureShock on 5/14/07.