The oiran, or Japanese courtesan, is a product of seventeenth century Japan. Like the geisha who eclipsed them in popularity, the oiran were not simply prostitutes; they were companions and performers, trained in a variety of arts — calligraphy, music, flower arranging — and prized for their ability to converse with powerful men. Though confined to the official pleasure districts of Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka, they were highly visible, formally parading through the streets in elaborate costumes, attended by a retinue of maids.

The oiran, or Japanese courtesan, is a product of seventeenth century Japan. Like the geisha who eclipsed them in popularity, the oiran were not simply prostitutes; they were companions and performers, trained in a variety of arts — calligraphy, music, flower arranging — and prized for their ability to converse with powerful men. Though confined to the official pleasure districts of Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka, they were highly visible, formally parading through the streets in elaborate costumes, attended by a retinue of maids.

As a potent symbol of the new, hedonistic culture of urban Japan, the oiran were frequent subjects of ukiyo-e, or “floating world” prints. Artists such as Suzuki Harunobou emphasized the oiran’s refinement, the rarefied world in which they operated, and, in their more explicit shunga prints, the bodily pleasures they offered.

Moyocco Anno’s Sakuran presents a less romanticized image of the oiran, documenting one girl’s rise from maid to tayuu, or head courtesan. We first meet Kiyoha as an eight-year-old child: orphaned and undisciplined, she chafes against the strict rules inside Edo’s Tamagiku House, making several unsuccessful attempts to escape. Shohi, Kiyoha’s mistress, is one of the few people to recognize Kiyoha’s potential: not only is Kiyoha quick-witted, she also boasts a porcelain complexion and delicate facial features, both highly prized assets in a courtesan. Shohi’s method for grooming Kiyoha for her new role is less tutoring than hazing, however, a mixture of slaps, insults, and mind games designed to teach Kiyoha to behave in a more dignified fashion.

Anno’s artwork is uniquely suited to the subject matter: it’s both starkly ugly and exquisitely beautiful, capable of conveying the anger and suffering beneath Kiyoha’s carefully manicured appearance. When we first meet Kiyoha, for example, Anno draws her as a “dirty little turnip” with a snot-stained face, unkempt hair, and an ill-fitting yukata. Though Kiyoha undergoes a remarkable transformation over the course of the manga, we are frequently reminded of what she looked like when she first arrived at Tamagiku. Kiyoha’s face contorts into a grotesque, child-like mask whenever she feels wronged or vulnerable, and she frequently reverts to a feral posture when eating, as if her bowl might be snatched from her hands.

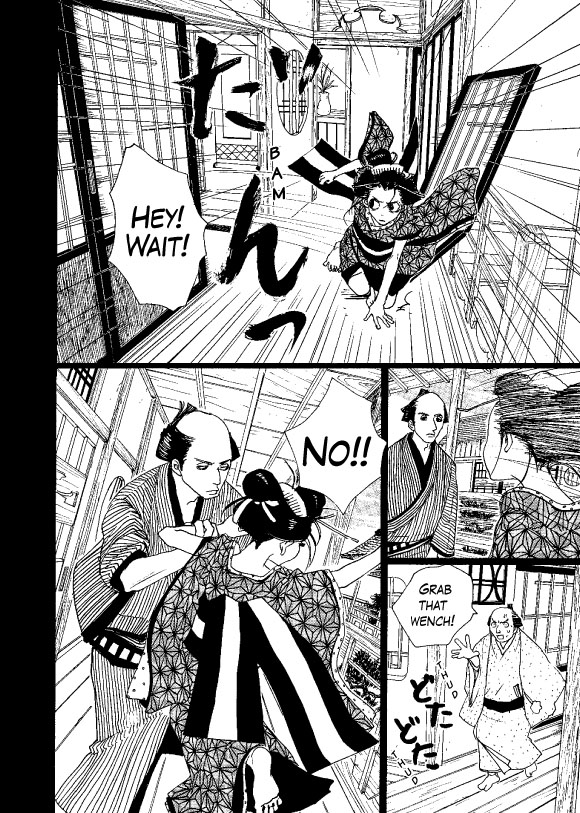

In this sequence, for example, twelve-year-old Kiyoha interrupts a transaction between a shinzu (the lowest ranking courtesan of the house) and a lecherous customer. Kiyoha’s motives for intervening are unclear, since her relationship with the shinzu in question is never carefully delineated. As she tussles with the customer, however, we see Kiyoha’s childhood survival instinct emerge in full force, overriding Shohi’s etiquette lessons:

One of the things this sequence also emphasizes is the discrepancy in power between the low-ranking courtesans and the house clientele; any violation of established protocol could result in severe reprisal. Anno infuses this scene with special urgency by using blunt, contemporary speech in lieu of the archaic language that verisimilitude might demand. It’s a welcome departure from the tortured, Fakespearian dialogue that plagues the otherwise brilliant Ooku: The Inner Chambers, focusing the reader’s attention on visual signifiers of class and gender — eye contact, body language, clothing — rather than honorifics and awkward syntax.

Perhaps Anno’s greatest achievement is her ability to capture her characters’ physical beauty and sensuality without reducing them to objects. Even the most erotic images are carefully framed as business transactions: the dialogue reminds us that the oiran are performing for their customers, creating an illusion of sexual and emotional intimacy for the sake of money, while their customers’ grim expressions and sweaty bodies remind us of their determination to get the most bang for the buck (so to speak).

If Sakuran sounds like a hectoring treatise on prostitution, rest assured it’s not. Anno creates a vibrant, fascinating world, teeming with people from every walk of life. Though her female characters have limited agency, they nonetheless find opportunities to exert influence over their customers, improve their social standing, and choose their own lovers.

Kiyoha embodies all the contradictions and complexities of her environment: she’s impetuous, competitive, and unmoved by her peers’ hardships, yet she has a great capacity for feeling — and transcending — pain. That Kiyoha is, at times, a repellant figure, does not diminish her appeal as a character; we appreciate the mental toughness that her job demands, and admire her efforts to push back against its limits. It seems only fitting that the story ends not with the outcome that a modern reader might choose for this fierce woman, but with one that reflects the heroine’s own clear-eyed understanding of what she is. Highly recommended.

Review copy provided by Vertical, Inc.