On a brilliant summer day in 1924, British explorer George Mallory began what would be his third and final attempt to climb Mt. Everest. Armed with oxygen tanks and masks, he and fellow mountaineer Andrew Irvine began their approach to the summit on the morning of June 8th, reaching the Northeast Ridge around one o’clock in the afternoon — a potentially fatal mistake, as they had barely enough time to reach the peak and return safely to camp before nightfall. Noel Odell, another member of Mallory’s expedition, spotted the pair ascending the so-called “steps,” three rock formations located 2,000 vertical feet below the top. As he would recall in the 1924 book The Fight for Everest, Odell caught a brief glimpse of his mates through a break in the cloud cover:

I saw the whole summit ridge and final peak of Everest unveiled. I noticed far away on a snow slope leading up to what seemed to me to be the last step but one from the base of the final pyramid, a tiny object moving and approaching the rock step. A second object followed, and then the first climbed to the top of the step. As I stood intently watching this dramatic appearance, the scene became enveloped in cloud once more, and I could not actually be certain that I saw the second figure join the first. (p. 130)

Odell was the last to see either man alive; for the next 75 years, Mallory and Irvine’s fate remained a mystery, though a few tantalizing clues — Irvine’s ice axe, Mallory’s discarded oxygen canister — suggested that neither had reached the top. In 1999, a joint American-British expedition recovered Mallory’s body not far from where Irvine’s axe was discovered, spurring new questions about their climb: had Odell, in fact, watched the men descending the Steps after a successful trip to the summit? Had Irvine and Mallory become separated on the mountain face, or did they fall together to their deaths? And where was Irvine’s body?

The mystery surrounding Mallory’s disappearance forms the core of Yumemakura Baku and Jiro Taniguchi’s award-winning series The Summit of the Gods. Based on a 1998 novel by Baku, Summit focuses on Makoto Fukamachi, a photographer who picks up Mallory’s trail in Kathmandu, where a 1924 Vestpocket Autographic Kodak Special — the camera Mallory supposedly carried up Everest — turns up in a second-hand store frequented by climbers and sherpas. As Fukamachi tracks the camera’s descent from Everest to Kathmandu, he crosses paths with Jouji Habu, a taciturn Japanese climber who knows more about the camera than he’s willing to reveal. Fukamachi begins trailing Habu, interrogating Habu’s acquaintances and climbing partners in hopes of learning what Habu is doing in Kathmandu. Though Fukamachi expects his questions will lead him to the camera’s source, he discovers instead that he and Habu have similarly haunting pasts: Fukamachi watched — and documented — two climbers fall to their deaths on an Everest glacier, while Habu tried — and failed — to rescue a climbing partner who lost his footing and plunged one hundred feet over a cliff in the Japanese Alps.

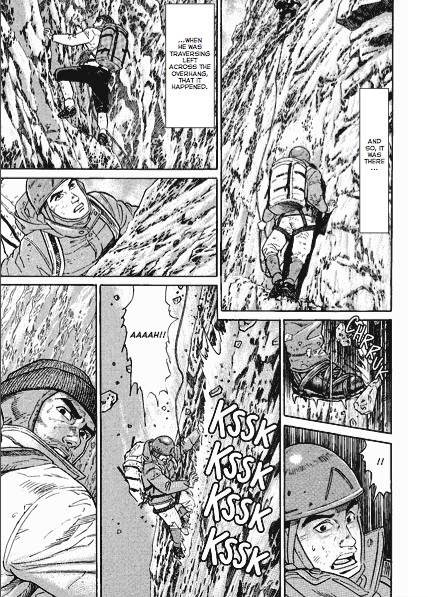

Both characters’ backstories are as harrowing as any passage from Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air, thanks to Taniguchi’s impeccable illustrations. Taniguchi captures the mountains’ desolation and danger with his meticulous renderings of rock formations, glaciers, and quick-changing weather patterns; one could be forgiven for wanting to clip into a securely anchored harness before reading volume one. Taniguchi’s talent for evoking the mood and energy of a landscape is also evident in his depiction of Kathmandu, a maze-like city filled with dead ends, bazaars, billboards, temples, and con artists eager to hustle European tourists. Through intricately detailed backgrounds juxtaposing squalid, overcrowded neighborhoods with sleek, modern buildings, Taniguchi suggests the city’s almost uncontainable energy.

The sheer beauty and power of these scenes distracts from the series’ biggest flaw: the omniscient narrator. In the afterward to volume one, Baku explains that he felt that Taniguchi was “the only artist” who could do justice to “the overwhelming massiveness of the mountains, the details of the climbing, the depictions of the characters.” In adapting his novel for a graphic medium, however, Baku never fully entrusts the artwork with the responsibility of telling the story; too often, Baku inserts unnecessary explanations into gracefully composed panels. In one scene, for example, Fukamachi dreams that he’s trailing a silent, mysterious figure up the summit of Everest, his calls going unheeded. To the reader, it’s obvious that Fukamachi is dreaming about Mallory, as Fukamachi has spent three days locked in his hotel room reading accounts of Mallory’s final climb. Yet the sequence is heavily scripted, with Baku decoding all of Taniguchi’s images rather baldly; it’s as if Baku is narrating the scene for someone who can’t see the pictures.

That Summit of the Gods remains compelling in spite of such editorial interventions is testament both to Taniguchi’s skill as a visual storyteller and to the story’s alluring location; as anyone who’s read Into Thin Air will tell you, the extreme conditions on Everest — the weather, the terrain, the frigid temperatures, the remoteness of the mountaintop — all but guarantee drama, even when the climbers are experienced and the weather cooperative. How Makafuchi and Habu will cope with these challenges remains to be seen, but it’s a sure bet that there will be plenty of nail-biting moments on the way to unraveling the mystery of what happened to George Mallory on that bright June day in 1924.

THE SUMMIT OF THE GODS, VOL. 1 • SCRIPT BY YUMEMAKURA BAKU, ART BY JIRO TANIGUCHI • FANFARE/PONENT MON • 328 pp. • NO RATING