Innocent is hard to pin down. On the one hand, it’s a meticulously researched period drama starring real-life figures such as Charles-Henri Sanson, Casanova, Robert-François Damiens, and Jeanne Bécu, the sort of thing you might see on Masterpiece Theater or HBO. On the other, it’s a lurid portrayal of a young man’s corruption, filled with over-the-top scenes of torture and debauchery that, intentionally or not, recall Justine, or The Misfortunes of Virtue. The tonal mismatch between its historical aspirations and its treatment of the principal character never gel into a coherent story, however, resulting in a handsome but repellant mess that isn’t serious enough to move the reader or ridiculous enough to be enjoyed as camp.

The series opens in 1793, then jumps back in time to reveal how Sanson evolved from a sensitive young man into the Royal Executioner of France. In making Sanson his protagonist, author Shin’ichi Sakamoto has a major hurdle to overcome: Sanson executed almost 3,000 people and championed the guillotine as a more efficient, humane tool for dispatching convicts. To ensure the reader’s sympathy lies firmly with Charles-Henri, therefore, Sakamoto commingles fact and fiction, depicting Sanson as a beautiful, raven-haired teen with flowing locks and trembling lips, the epitome of a guileless young man. Everything makes Charles-Henri’s enormous eyes glisten with tears: the cruel comments of boarding school classmates, the sound of a flute, the sight of a beautiful young aristocrat. He’s also prone to outbursts of teenage indignation and fits of nausea, unable to stomach his father’s lessons on how to decapitate a person with a single blow.

For all the feverish dialogue and graphic violence, there’s almost no meaningful character development, as Sakamoto seems more intent on demonstrating Charles-Henri’s capacity for suffering than in depicting a flesh-and-blood person’s efforts to resist his destiny. In one of the most egregious examples of this tendency, Père Sanson tortures his son with techniques cribbed from the Book of Martyrs: he shackles Charles-Henri to a chair, deprives him of food and water, pierces his skin, and pulverizes his legs with a sledgehammer in an effort to bend Charles-Henri to his will. The true horror of the scene, however, is undercut by the way in which Sakamoto luxuriates in Charles-Henri’s wounded body with same fervid zeal as Titian painted the Crucifixion; Charles-Henri is stripped to waist and strapped to a pole, his hands tied above his head as he cries out in bewilderment. And if those Baroque flourishes aren’t enough to ruin the scene’s emotional authenticity, the cartoonishly evil Père Sanson is; he’s less a fully-realized character than a foil for Charles-Henri’s innocence, prone to making over-the-top pronouncements that would be right at home in a Nicholas Cage flick.

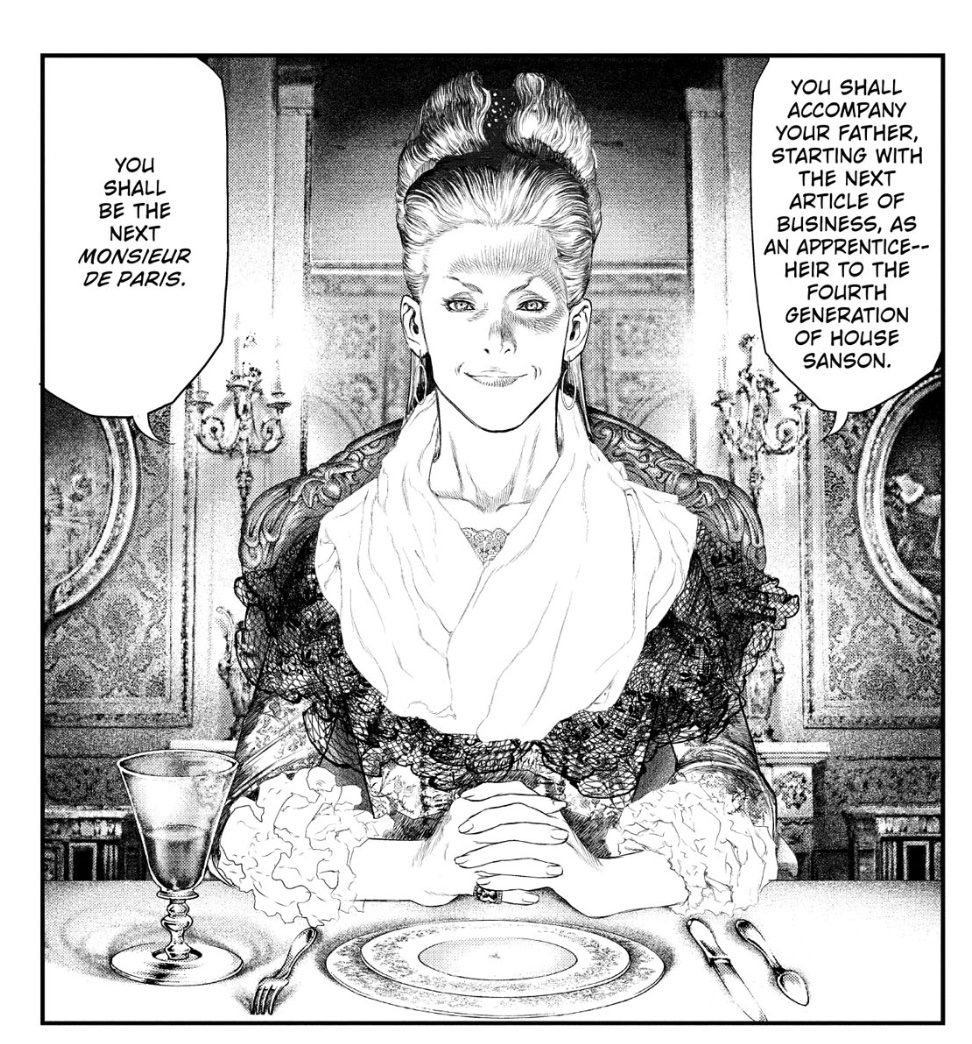

If the narrative disappoints, the artwork does not. Sakamoto draws sumptuous costumes and grand estates, lavishing considerable attention on small but historically meaningful details—a china pattern, the buckle of a shoe—in a meticulous effort to evoke the material culture of eighteenth century France. His real gift, though, is making obscure historical figures come to life on the page. Anne-Marthe Sanson, the matriarch of the Sanson clan, is a prime example: she looks like a bird of prey with a piercing stare and sharp nose, an impression reinforced by the way her fichu drapes across her chest like a ruff. In several key scenes, Sakamoto illuminates her from below, casting her face into shadowy relief to reveal the full extent of her hawkish vigilance:

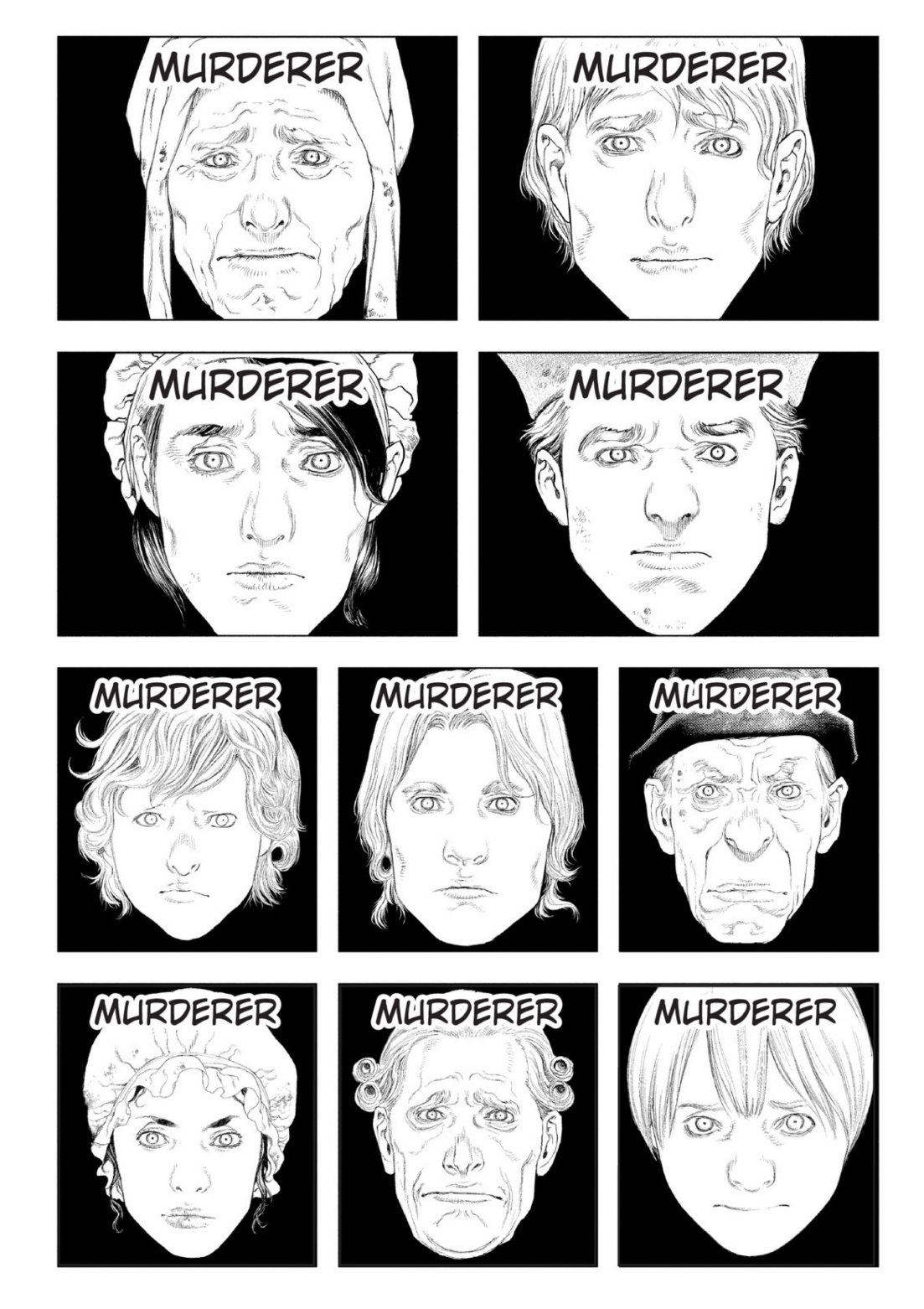

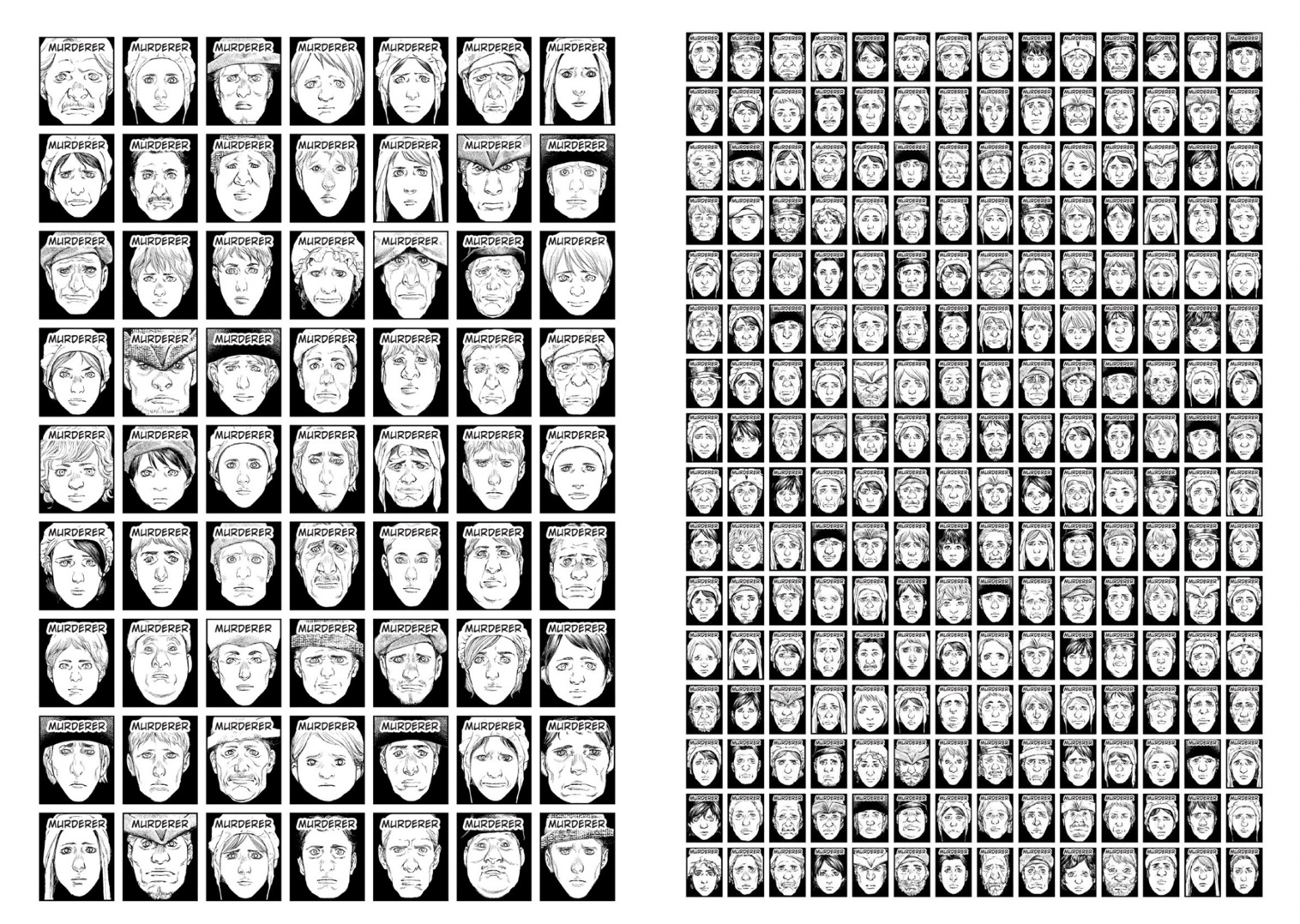

Sakamoto also has a flair for using abstraction, fantasy, and non-sequiturs to reveal his characters’ innermost thoughts. Not all of these gambits work; in one visually jarring moment, for example, Sakamoto depicts Charles-Henri in modern streetwear, an image that serves no obvious dramatic purpose. Other scenes, however, are devastatingly effective in conveying the full extent of Charles-Henri’s paranoia and loneliness. After botching the execution of an acquaintance, Sanson looks out at the crowd and sees a motley assortment of faces staring at him: Sakamoto then repeats this motif, adding more and more faces:

Sakamoto then repeats this motif, adding more and more faces: It’s a simple but powerful sequence: we feel the collective weight of the crowd’s revulsion and the individual opprobrium of everyone who witnessed Sanson’s orgiastic display of violence. At the same time, however, we feel Sanson’s growing sense of terror and confinement, imprisoned in a role he loathes and unable to escape the scrutiny of commoners and noblemen alike.

It’s a simple but powerful sequence: we feel the collective weight of the crowd’s revulsion and the individual opprobrium of everyone who witnessed Sanson’s orgiastic display of violence. At the same time, however, we feel Sanson’s growing sense of terror and confinement, imprisoned in a role he loathes and unable to escape the scrutiny of commoners and noblemen alike.

These kind of emotionally resonant scenes are few and far between, however, as Sakamoto is more interested in showing Charles-Henri’s martyrdom than making him into a real person; you’d be forgiven for thinking that Sanson was a real-life saint and not someone who’s remembered today for his enthusiastic embrace of the guillotine. Not recommended.

INNOCENT, VOL. 1 • STORY AND ART BY SHIN’ICHI SAKAMOTO • TRANSLATED BY MICHAEL GOMBOS • LETTERING AND RETOUCH BY SUSIE LEE AND STUDIO CUTIE • DARK HORSE • 632 pp. • RATED 18+ (Violence, nudity, language)