While reading Comics: A Global History, 1968 to the Present, I encountered a single sentence that particularly caught my attention: “Star Reach was also notable for printing the first Japanese comics to be translated into English, two short pieces by Masaichi Mukaide; the style displayed was not characteristically Japanese, however, and failed to ignite any further interest in importing manga for the time being.”

Masaichi Mukaide. Though at that point I was unfamiliar with Star Reach, I was pretty sure that I had come across Mukaide’s name somewhere before. And so I decided to investigate.

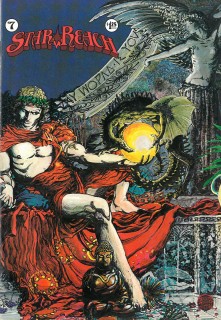

Star Reach was an influential independent American comics anthology that focused on science fiction and fantasy stories. Mike Friedrich, who was once an editor and writer at both DC Comics and Marvel, established his own press in order publish Star Reach, which began in 1974. In 1978, he also started to release Star Reach‘s sister publication Imagine. At one point or another, both of those magazines included short works by Mukaide. Some of the comics were entirely his own creation while others were collaborations with different writers, both Japanese and American–notably Lee Marrs and Steven Grant. The first of Mukaide’s comics to appear in English, “The Bushi,” was written by Satoshi Hirota and was published in the seventh issue of Star Reach January 1977.

In an interview with Friedrich included in the Star Reach Companion, Richard Arndt asked how it came about that Star Reach published the first manga to appear in America. Friedrich replied:

I’ve never met the Japanese artist I published, although we did present a fair amount of his work. Oddly enough, he’s not a comic book artist in Japan. He was basically a fan artist over there. He could not make his living as an artist in Japan because his work was considered too American! If you look at it now, it was probably the first combination of manga and American comics. His work didn’t quite fit anywhere. But, yeah, there’s a book, Manga! Manga!, which certifies that the first appearance of manga in the United States was in Star Reach. I had no idea that was true.

Well, it turns out that technically isn’t true–Ryan Sands has noted that a 1971 issue of Concerned Theatre Japan included three short manga in translation–but for all intents and purposes, Mukaide’s work was the first exposure that the average comics reader in the United States had to manga.

Try as I might, I’ve been unable to find very much information about Mukaide himself. The best clue that I’ve discovered comes from Friedrich’s editor’s note accompanying Star Reach #18, the magazine’s final issue:

A friend of Masaichi Mukaide dropped by the other day and I found out a bit more about our distant Japanese contributor. He’s a law school graduate who opted out of a legal career to enter the publishing world and keep up his art. His wife is also an artist, working on the local comics (I believe I was told).

However, that’s not the last that was seen of Mukaide in English. Sometime between 1980 and 1982 a volume simply called Manga was released. (ISBN 4946427015 for those who are interested in trying to track down a copy.) This collection is the reason that Mukaide’s name seemed familiar to me–his comic, “The Promise,” concludes the volume. He was also the editor of the collection. Looking more closely at Manga‘s credits, there are also some other names that I now recognize: Friedrich served as the consulting editor, Hirota was the associate editor, and Marrs was a contributing writer.

Manga was one of the first collections deliberately crafted in order to introduce Japanese comics to Western audiences: “Our purpose in publishing Manga is to give the non-Japanese reading public a visual taste of Japan and the creative talents that exist there. Nothing would give us greater pleasure, however, if in doing so we are able to boost the cultural understanding in the west about Japan.”

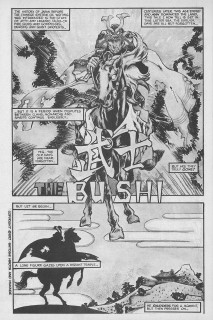

As already mentioned, the first work by Mukaide to appear in English was “The Bushi,” which was written by Satoshi Hirota. Were it not for the historical Japanese setting, there is very little to indicate that the creators themselves were also Japanese. Mukaide’s artwork is not all that different from many of the other comics found in Star Reach. The story is set during the tumultuous time between the age of myth and legends and the age of humans. A young warrior confronts and battles with a demon, seeking revenge for the slaughter of his family, only to become a demon himself.

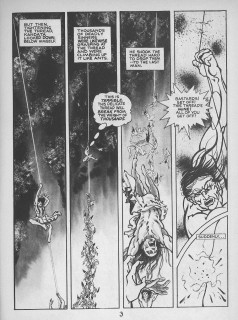

“The Spider Thread” is based on the well-known short story “The Spider’s Thread” written by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa in 1918. In it, a sinner is given the chance to escape hell because he once saved the life of a spider–the only good deed that he ever committed. However, Mukaide gives his own little twist to the tale at the end of the comic. Considering the seriousness and drama of the story–it almost entirely takes place among the tortured souls in hell–the final panel is surprisingly humorous, turning the comic into a joke. “The Spider Thread” also contains what is probably my favorite single page composed by Mukaide.

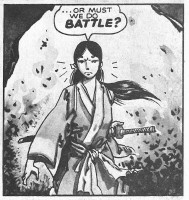

Mukaide’s first collaboration with writer Lee Marrs, “The Awakening of Tamaki,” was apparently intended to be the start of a series which would follow the trials of a young woman named Tamaki. After her family is killed, Tamaki is raised in seclusion by her sole-surviving uncle. When he dies as well she must make her own way in the world, disguised as a boy for the sake of her safety. Thanks to her uncle’s training, Tamaki is an excellent swordswoman with exceptional moral strength. As far as I know, there were never any more installments in the series, which is a shame; I really liked the comic.

“The Mission” was Mukaide’s second collaboration with Marrs. Whereas I was very fond of “The Awakening of Tamaki,” “The Mission” is probably my least favorite of Mukaide’s comics in English. It seems like it should be a something that I would enjoy, but it just didn’t grab me. Despite the numerous twists and turns the story takes within its few pages, despite the lies and betrayals, despite the quick pace and all of the action and fighting, for some reason “The Mission” simply strikes me as somewhat generic ninja adventure. Ninja doesn’t even have a name; he’s just Ninja.

When compared to the rest of Mukaide’s English-language comics, the two-paged “Salvation” stands out because the artwork and story is so simple. Backgrounds are almost nonexistent and the shading and detail of the illustrations are limited as well. The story follows a drunkard who keeps getting kicked out of drinking establishments. He causes a panic by claiming that a doomsday flood is coming in order to sneak back into the bars after everyone else has fled. It’s an amusing and silly short comic that, like most of Mukaide’s other comics, has a bit of a twist at the end.

“The Soldier Who Guards the Gate of the City Freedom” is another two-paged comic by Mukaide, although it is more of a historical allegory instead of a humorous gag like “Salvation.” A young soldier, a man of honor, has the lonely duty of guarding the city gates. He does so willingly, though the eventual enemy attack is a long time in coming. Mukaide’s emphasis on the soldier’s loneliness is the key to the impact of the brief comic. The steady passage of time, too, is important. Mukaide captures this through the use of a very regular progression of narrow panels which are all of the exact same size.

“Crashing,” which was written by Steven Grant, is the only example of Mukaide’s work in the genre of science fiction. All of his other comics published in English are historical in nature, generally with touches of the fantastic. Mukaide’s artwork in “Crashing” is not at all dissimilar to American science fiction comics of the era. It’s a somewhat confusing story, but this is exceedingly appropriate as the comic’s protagonist has gone insane. Mukaide’s artwork supports this as well–the illustrations can be somewhat hallucinogenic and the page layouts are often fragmented.

“The Promise,” the last of Mukaide’s comics to be translated, is his rendition of the legend of the Yuki-onna, or the Snow Woman. Lafcadio Hearn’s telling of the story in Kwaidan is probably the version with which English-language audiences are most familiar. Mukaide’s tale incorporates many of the same elements as Hearn’s, but he adds his own touches as well. “The Promise” also shares some similarities with “The Bushi,” especially in style, although “The Promise” tends to be stronger overall. However, the two comics bookend Mukaide’s excursion into English particularly nicely because of their parallels.

After that, Mukaide seems to disappear. I have no idea what happened to him or if he’s even still creating comics. Perhaps he went back to working in law. Either way, a small corpus of Mukaide’s comics released in English in the late 1970s and early 1980s does exist. What particularly strikes me about these works are the changes and adjustments that he makes to his art style and page layouts to better suit each story being told. Although each comic is definitely its own work, there are some common elements as well. For example, his narratives and artwork frequently draw inspiration from traditional stories, tales, and legends. Interestingly, although many of his comics take place within a vaguely historical Japanese setting, he does not exclusively limit himself to Japanese sources. Instead, Mukaide’s work blends together both Eastern and Western influences, which seems oddly fitting for one of the first Japanese comics creators to be released in English.

Masaichi Mukaide Bibliography

- “The Awakening of Tamaki” written by Lee Marrs and illustrated by Masaichi Mukaide (Imagine #4, October 1978)

- “The Bushi” written by Satoshi Hirota and illustrated by Masaichi Mukaide (Star Reach #7, January 1977)

- “Crashing” written by Steven Grant and illustrated by Masaichi Mukaide (Star Reach #18, October 1979)

- “The Mission” written by Lee Marrs and illustrated by Masaichi Mukaide (Star Reach #15, December 1978)

- “The Promise” written and illustrated by Masaichi Mukaide (Manga, 1980/1982?)

- “Salvation” written and illustrated by Masaichi Mukaide (Imagine #6, June 1979)

- “The Soldier Who Guards the Gate of the City Freedom” written and illustrated by Masaichi Mukaide (Star Reach #18, October 1979)

- “The Spider Thread” written and illustrated by Masaichi Mukaide (Imagine #3, July 1978)

Further Reading

Comics: A Global History, 1968 to the Present by Dan Mazur and Alexander Danner

Early Manga: A Chronology by Ryan Sands

Incredible First-Ever Manga Translated in 1971 by Ryan Sands

Manga and Mega Comics by Jason Thompson

Manga in the USA by Michael Toole

My Life is Choked with Comics #19a: Manga by Joe McCulloch

My Life is Choked with Comics #19b: Manga by Joe McCulloch

Star Reach Companion by Richard Arndt