Since its debut in Bessatsu Shōjo Comic, Moto Hagio’s The Poe Clan has proven almost as enduring as its vampire protagonists, living on in the form of radio plays, CD dramas, a television series, a Takarazuka production, and a sequel that appeared in Flowers forty years after the series finished its initial run. The Poe Clan’s success is even more remarkable considering that Hagio was in the formative stages of her career, having made her professional debut just three years earlier with the short story “Lulu to Mimi.” Yet it’s easy to see why this work captivated female readers in 1972, as Hagio’s fluid layouts, beautiful characters, and feverish pace brought something new to shojo manga: a story that luxuriated in the characters’ interior lives, using a rich mixture of symbolism and facial close-ups to convey their ineffable sorrow.

The Poe Clan‘s principal characters are Edgar and Marybelle Portsnell, the secret, illegitimate children of a powerful aristocrat. When their father’s new wife discovers their existence, Edgar and Marybelle’s nursemaid leads them into a forest and abandons them. The pair are rescued by Hannah Poe, a seemingly benevolent old woman who plans to induct them into her clan when they come of age. The local villagers’ discovery that the Poes are, in fact, vampirnellas (Hagio’s term for vampires) irrevocably alters Hannah’s plans, however, setting in motion a chain of events that lead to Edgar and Marybelle’s premature transformation into vampirnellas.

Though my plot summary implies a chronological narrative, The Poe Clan is more Moebius strip than straight line, beginning midway through Edgar and Marybelle’s saga, then shuttling back and forth in time to reveal their father’s true identity and introduce a third important character: Alan Twilight, the scion of a wealthy industrialist whose confidence and beauty beguile the Portsnell siblings. In less capable hands, Hagio’s narrative structure might feel self-consciously literary, but the story’s fervid tone and dreamy imagery are better served by a non-linear approach that allows the reader to immerse themselves in Edgar’s memories, experiencing them as he does: a torrent of feelings. Furthermore, Hagio’s time-shifting serves a vital dramatic purpose, helping the reader appreciate just how meaningless time is for The Poe Clan’s immortal characters; they cannot age or bear children, nor can they remain in any school or village for more than a few months since their unchanging appearance might arouse suspicion.

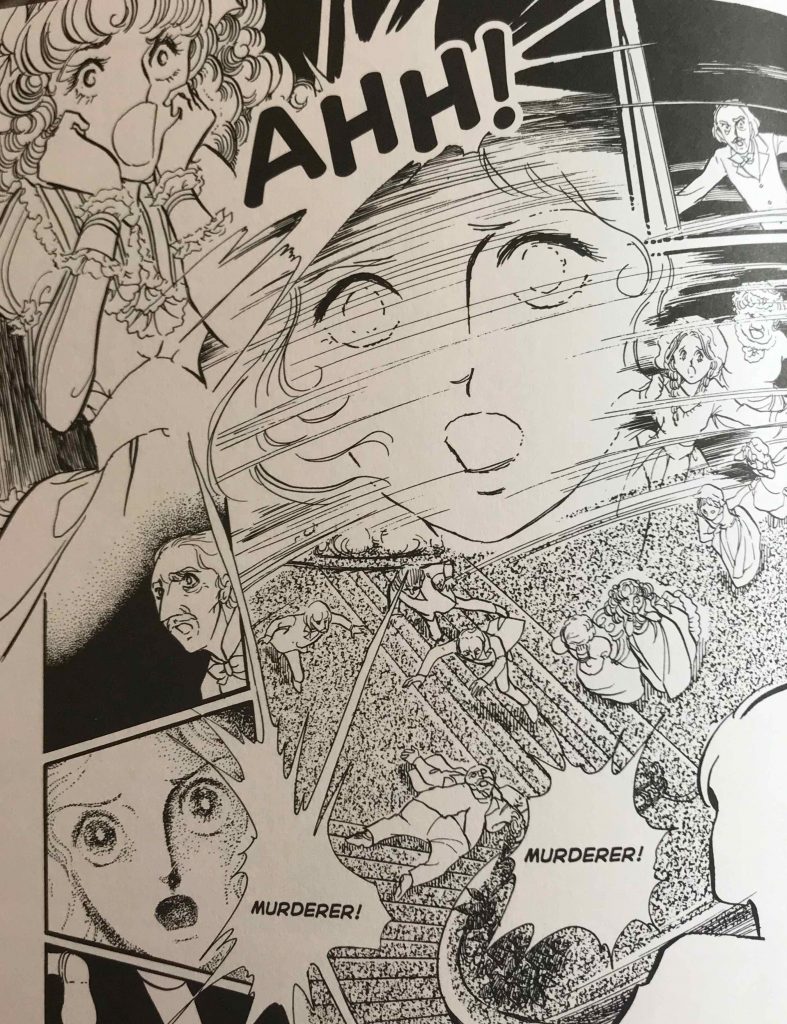

Hagio’s artwork further reinforces the dreamlike atmosphere through inventive use of panel shapes and placement, with characters bursting out of frames and tumbling across the page, freeing them from the sequential logic of the grid. In this scene, for example, Hagio uses these techniques to depict an act of impulsive violence—Alan pushes his uncle down a flight of stairs—as well as the reaction of the servants and relatives who bear witness to it:

While the influence of manga pioneers like Osamu Tezuka and Shotaro Ishinomori is evident in the dynamism of this layout, what Hagio achieves on this page is something arguably more radical: she uses this approach not simply to suggest the speed or force of bodies in motion, or the simultaneous reactions of the bystanders, but to convey the intensity of her characters’ feelings, a point reinforced by the facial closeups and word balloons that frame the uncle’s crumpled body.

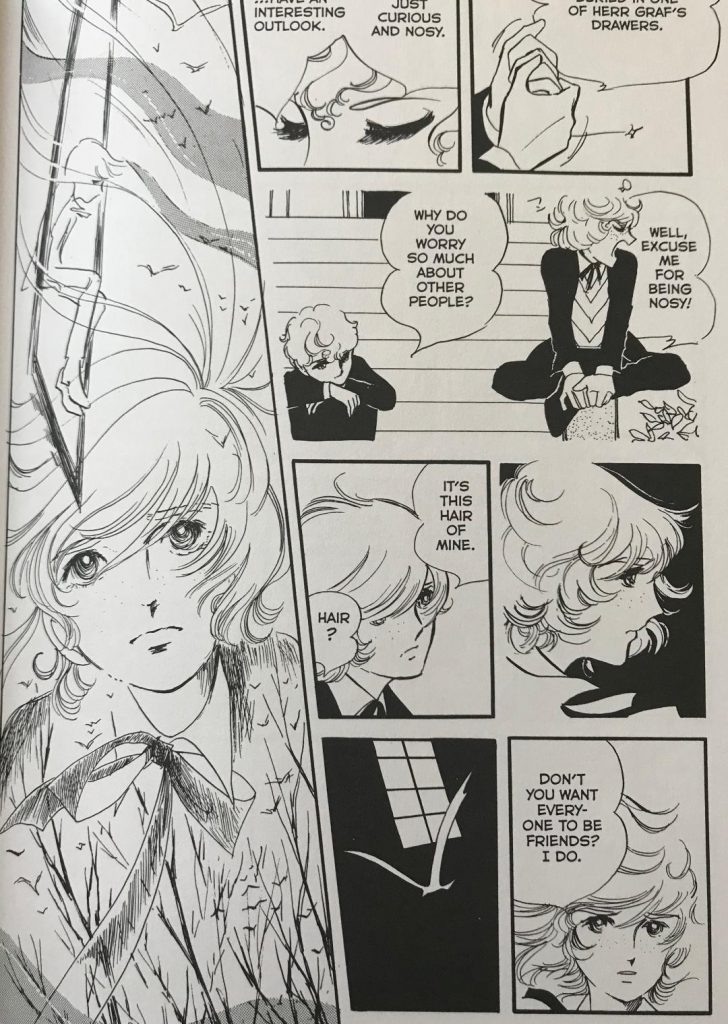

Her method for representing memories is likewise artful. Through layering seemingly arbitrary images, she creates a powerful analogue for how we remember events—not as a complete, chronological sequence but a vivid collage of individual moments and details. In this passage, Hagio reveals why one of Edgar’s schoolmates has confessed to a theft he didn’t commit:

The final frame of this passage reveals the source of Killian’s pain: he witnessed another boy’s suicide. But Killian isn’t remembering how the event unfolded; he’s remembering the things that caught his eye—birds and branches, feet dangling from a window—and his own feelings of helplessness as he realized what his classmate was about to do.

As ravishing as the artwork is, what stayed with me after reading The Poe Clan is how effectively it depicts the exquisite awfulness of being thirteen. Alan, Edgar, and Marybelle feel and say things with the utmost sincerity, so caught up in the intensity of their emotions that nothing else matters. Through the metaphor of vampirism, Hagio validates the realness of their tweenage mindset by depicting their existence as an endless cycle of all-consuming crushes, sudden betrayals, and confrontations with hypocritical, dangerous, or bumbling adults. At the same time, however, Hagio invites the reader to see the tragedy in the Portsnells’ dilemma; they are prisoners of their own immaturity, unable to achieve the emotional equilibrium that comes with growing up.

One final note: Fantagraphics deserves special praise for their elegant presentation of this shojo classic. Rachel Thorn’s graceful translation is a perfect match for the imagery, conveying the characters’ fervor in all its adolescent intensity, while the large trim size and substantial paper stock are an ideal canvas for Hagio’s detailed, vivid artwork. Recommended.

This post was updated on August 23rd with more accurate information about the current status of The Poe Family‘s serialization in Flowers. Special thanks to Eric Henwood-Greer for the correction!

THE POE CLAN, VOL. 1 • ART AND STORY BY MOTO HAGIO • TRANSLATED BY RACHEL THORN • FANTAGRAPHICS • 512 pp. • NO RATING

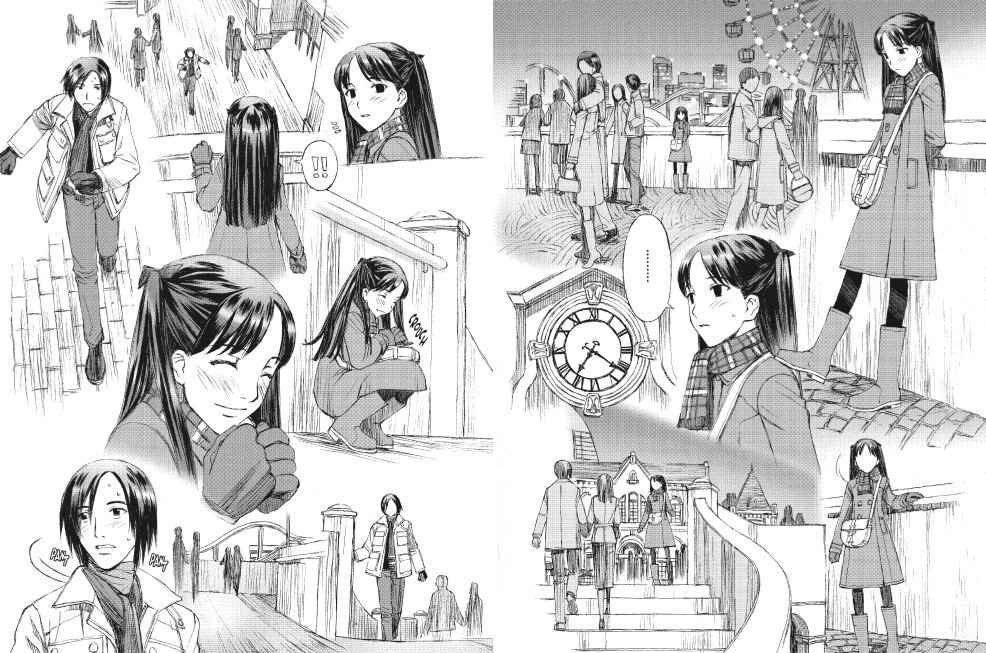

The eponymous heroine of Canon is a smart, tough-talking vigilante who’s saving the world, one vampire at a time. For most of her life, Canon was a sickly but otherwise unremarkable human — that is, until a nosferatu decided to make Lunchables™ of her high school class. Canon, the sole survivor of the attack, was transformed into a vampire whose blood has an amazing property: it can restore other victims to their former human selves. She’s determined to rescue as many human-vampire converts as she can, prowling the streets of Tokyo in search of others like her. She’s also resolved to find and kill Rod, the handsome blonde vampire whom she believes murdered her friends. Joining her are two vampires with agendas of their own: Fuui, a talking crow who’s always scavenging for blood, and Sakaki, a half-vamp who harbors an even deeper grudge against Rod for killing his family.

The eponymous heroine of Canon is a smart, tough-talking vigilante who’s saving the world, one vampire at a time. For most of her life, Canon was a sickly but otherwise unremarkable human — that is, until a nosferatu decided to make Lunchables™ of her high school class. Canon, the sole survivor of the attack, was transformed into a vampire whose blood has an amazing property: it can restore other victims to their former human selves. She’s determined to rescue as many human-vampire converts as she can, prowling the streets of Tokyo in search of others like her. She’s also resolved to find and kill Rod, the handsome blonde vampire whom she believes murdered her friends. Joining her are two vampires with agendas of their own: Fuui, a talking crow who’s always scavenging for blood, and Sakaki, a half-vamp who harbors an even deeper grudge against Rod for killing his family. Forget what you know about the Russian Revolution. The real cause of the Romanov’s demise wasn’t growing unrest among the proletariat, the intelligentsia, or the military; nor the high cost of World War I; nor the famines of 1906 and 1911, but something far more sinister: vampires. At least, that’s the central thesis of Blood+ Adagio, a prequel to the popular anime/manga series about an immortal, vampire-slaying schoolgirl and her handsome, enigmatic handler. The first volume of Adagio transplants Saya and Hagi from the steamy jungles of present-day Okinawa and Vietnam — where they’ve battled US military forces and the myserious Cinq Flèches Group — to the chilly halls of Nicholas II’s Winter Palace in St. Petersburg — where they discover a nest of Chiropterans (a.k.a vampires who are more beast than bishie) as well as a host of schemers, sycophants, and crazy folk in the tsar’s orbit. Let the slayage begin!

Forget what you know about the Russian Revolution. The real cause of the Romanov’s demise wasn’t growing unrest among the proletariat, the intelligentsia, or the military; nor the high cost of World War I; nor the famines of 1906 and 1911, but something far more sinister: vampires. At least, that’s the central thesis of Blood+ Adagio, a prequel to the popular anime/manga series about an immortal, vampire-slaying schoolgirl and her handsome, enigmatic handler. The first volume of Adagio transplants Saya and Hagi from the steamy jungles of present-day Okinawa and Vietnam — where they’ve battled US military forces and the myserious Cinq Flèches Group — to the chilly halls of Nicholas II’s Winter Palace in St. Petersburg — where they discover a nest of Chiropterans (a.k.a vampires who are more beast than bishie) as well as a host of schemers, sycophants, and crazy folk in the tsar’s orbit. Let the slayage begin!