By Fumi Yoshinaga | Published by Digital Manga Publishing

When Fumi Yoshinaga sets a series in high school, you just know that she’s not going to do it like anybody else.

When Fumi Yoshinaga sets a series in high school, you just know that she’s not going to do it like anybody else.

Harutaro Hanazono is beginning his first year of high school thirteen months behind schedule due to a bout of leukemia. The manga begins as he introduces himself to his new classmates in a manner that communicates much about his character. He’s an honest, simple, and idealistic soul, so is very forthright with his classmates about his illness because he doesn’t like the prospect of keeping secrets from all of them or having to explain multiple times. What he fails to consider, however, is how this information will affect his classmates’ interactions with him, since they all treat him with more consideration than they might otherwise have done.

Harutaro quickly becomes friends with Shota Mikuni, a gentle, smart, and adorable overweight boy whose main flaw is his timidity. Mikuni is also friends with Kai Majima, an arrogant otaku who is such a fascinating character that he’s going to get his own paragraph later. Harutaro and Majima don’t get along very well, but this doesn’t stop Harutaro from joining Mikuni and Majima in the manga club, where he collaborates with Mikuni and gradually develops the ambition to become a professional manga artist.

Meanwhile, readers become acquainted with the rest of the class in the same organic way any new student would. The homeroom teacher is Shigeru Saito, who at first appears to be an effeminate gay man but who is actually a woman. (Yoshinaga fooled me there, I must admit.) Other classmates include Yamane, a mature student with a love for books; Sakai, a perpetually tardy girl with a knack for English; Aizawa, a girl sensitive to the feelings of others; Jinnai and Isonishi, close friends and nice, normal girls; Ozaki, a rather boisterous fellow; and Tsuji, a guy who looks so much like Ono from Antique Bakery that it’s disconcerting to see him nurturing feelings for a woman.

Meanwhile, readers become acquainted with the rest of the class in the same organic way any new student would. The homeroom teacher is Shigeru Saito, who at first appears to be an effeminate gay man but who is actually a woman. (Yoshinaga fooled me there, I must admit.) Other classmates include Yamane, a mature student with a love for books; Sakai, a perpetually tardy girl with a knack for English; Aizawa, a girl sensitive to the feelings of others; Jinnai and Isonishi, close friends and nice, normal girls; Ozaki, a rather boisterous fellow; and Tsuji, a guy who looks so much like Ono from Antique Bakery that it’s disconcerting to see him nurturing feelings for a woman.

Because Yoshinaga introduces the cast of students in such a natural-feeling way, I found myself caring about them much more than I ordinarily do in a series set in high school. For one thing, I’m not sure there is any other series where I could rattle off the names and personality traits of seven supporting classmates. It doesn’t matter that these characters may not get tons of page time; they’re still fully realized people with their own problems and passions. I’ve written before about my weariness regarding school cultural festivals, but in Yoshinaga’s hands, the festival in the second volume of the series is the best I have ever read, hands down. For the first time, I really engaged with the excitement the characters were experiencing. The same holds true for the Christmas party they hold in volume three. (Plus, that dinky tree was genuinely amusing.)

One of the major things I love about Flower of Life is how Yoshinaga works in some subtle lessons on friendship into the story. Sumiko Takeda is not in Harutaro’s class but becomes friendly with them when her original shoujo manga is circulated around and becomes a hit. Takeda doesn’t care about fashion or clothes, and she’s at a loss when her mother gives her some money to buy an outfit for herself. While shopping, she runs into Jinnai and Isonishi, who decide to come along as consultants. Their first shopping experience is kind of a drag, as Takeda is unenthused by the clothes shopping and Jinnai and Isonishi are bored when Takeda geeks out in an art supply store, but on a second attempt, they’re able to work out an arrangement where everyone can pursue their individual interests and yet still have a good time together. This seems to say “You can like different things and still be friends.” Other lessons that crop up later include “You don’t need to try to impress your friends,” “There can be one-sided feelings even in friendship,” and “You might think it’s nice to be coddled, but is it really good for you?”

Another lesson, “You can disagree and still be friends,” is vitally important to Mikuni. He begins the series a timid guy, unwilling to stand out by expressing his opinion. When he gets passionate enough about something, though—and it’s usually manga—he will speak out. The first time this happens with Harutaro, Mikuni is worried that he’s damaged their friendship, but Harutaro is actually thrilled that Mikuni was able to express himself so honestly and their friendship deepens as a result. By the end of the series, Mikuni has gained enough confidence to express his vision to Takayama, the manga editor who gives their work a harsh critique, and rebound from criticism with a zeal to improve.

Another lesson, “You can disagree and still be friends,” is vitally important to Mikuni. He begins the series a timid guy, unwilling to stand out by expressing his opinion. When he gets passionate enough about something, though—and it’s usually manga—he will speak out. The first time this happens with Harutaro, Mikuni is worried that he’s damaged their friendship, but Harutaro is actually thrilled that Mikuni was able to express himself so honestly and their friendship deepens as a result. By the end of the series, Mikuni has gained enough confidence to express his vision to Takayama, the manga editor who gives their work a harsh critique, and rebound from criticism with a zeal to improve.

I’ve talked quite a lot about the student characters, but the adults figure into the story in big ways, as well. The manga club members discover early on that Saito-sensei is carrying on an affair with the very married Koyanagi-sensei, who used to be her teacher when she was a student ten years ago. Their troubled relationship dominates her thoughts until she finally calls it off in volume three, saying that she loved him because he was such a good father, and it pains her to see him sneaking around and betraying his family. Koyanagi’s unexpected successor is Majima, whose solution to Saito’s woes is to give her something else to be “moeh” about.

And now we come to Majima. I love that in painting this portrait of an otaku, Yoshinaga didn’t just give us a heavy-breathing perv with a penchant for maid costumes, but really shows us how he thinks and attempts to process the world. He is arrogant and a little creepy, with a large quantity of disdain for his fellow students. He seems to prefer 2-D representations of women with specific physical qualities over real women, whom he appears to resent. And yet… although initially detached and unfeeling in his relationship with Saito, he eventually comes a bit unhinged when her behavior—saying she loves him yet sleeping with Koyanagi—does not follow logical patterns. I don’t think he loves her, or is capable of really loving anyone, but he expected her feelings for him to stay the same—the only thing he knows about relationships he’s learned from manga and dating sims, where you win the girl and then she loves you always—and is completely thrown when this doesn’t turn out to be the case. I think the experience makes him a tiny bit more empathetic to others, and maybe it’ll be what he needs to become a better person, but man, how thoroughly unfair of Saito to embroil this poor kid in an adult love triangle that he was not remotely equipped to participate in. My opinion of her suffered a great deal as a result.

The plight of Harutaro’s homebound sister, Sakura, also plays a major role in the story, furnishing some surprisingly dark moments and eventually culminating in the revelation that Harutaro is not, as he had believed, fully cured. He takes the news hard, but once he’s had the chance to process it, he returns to school for his second year a changed man. For, you see, he has learned to lie. He has learned to consider the feelings of others before he speaks. Gone is the Harutaro that can’t abide secrets. Now we see that he has learned discretion—he might want to tell Mikuni the truth, but he will wait for a time when his friend is ready to hear it. He can keep it to himself for as long as it takes. He has grown up.

The plight of Harutaro’s homebound sister, Sakura, also plays a major role in the story, furnishing some surprisingly dark moments and eventually culminating in the revelation that Harutaro is not, as he had believed, fully cured. He takes the news hard, but once he’s had the chance to process it, he returns to school for his second year a changed man. For, you see, he has learned to lie. He has learned to consider the feelings of others before he speaks. Gone is the Harutaro that can’t abide secrets. Now we see that he has learned discretion—he might want to tell Mikuni the truth, but he will wait for a time when his friend is ready to hear it. He can keep it to himself for as long as it takes. He has grown up.

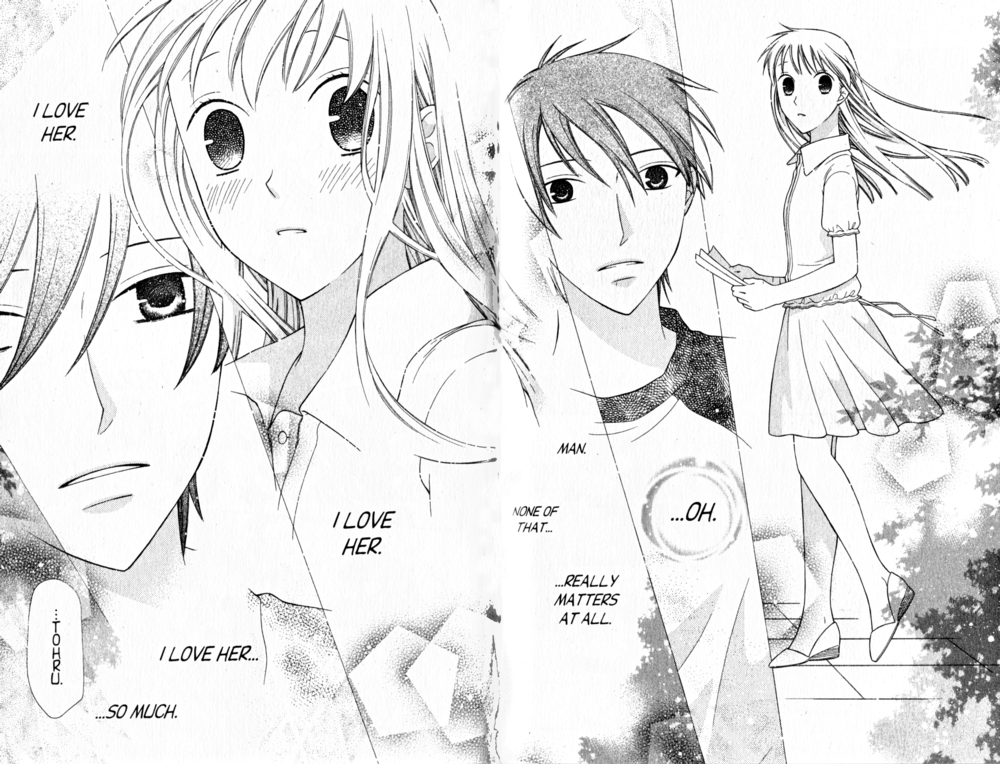

Lastly, I wanted to touch upon the art in the story, especially the nonverbal storytelling that Yoshinaga employs with such aplomb. The page below is from volume three, when Harutaro has gone to the hospital for his monthly exam. He speaks with the nurse about a fellow patient who has since died, and when he emerges from the hospital, he pauses to look up at the sky for a moment then continues on his way. He doesn’t say a thing, but it his thoughts are absolutely clear: “She will never see this sky again.”

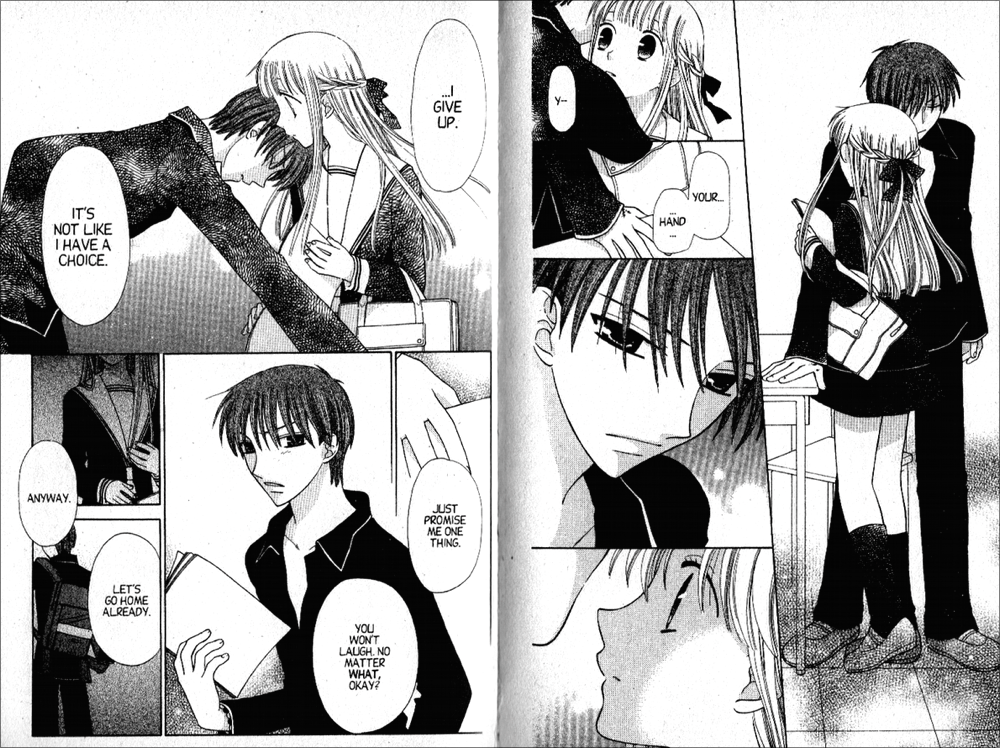

Another trait of Yoshinaga’s art is the repetition of similar panels to highlight the evolution of a facial expression (see MJ’s example from Antique Bakery in a Let’s Get Visual column from last October) or situation. In the example below, from volume four, she not only uses this technique to show Majima as someone not fully invested in the drama of the moment, but also for simple humorous effect.

Flower of Life is really an extraordinary series. When Harutaro and Mikuni are working on their manga, they express the desire to include some universal truths about friendship and growing up in their story, and that is precisely what Fumi Yoshinaga has done. It’s funny, it’s touching, and it’s a classic. Go read it.

Flower of Life was published in English by Digital Manga Publishing and is complete in four volumes. I reviewed it as part of the Fumi Yoshinaga Manga Moveable Feast, the archive of which can be found here.

Review copy for volume four provided by the publisher.

SEAN: It’s a smaller week this time around, but even if there were tons of titles, my pick would likely be the same. I found the first volume of Q Hayashida’s

SEAN: It’s a smaller week this time around, but even if there were tons of titles, my pick would likely be the same. I found the first volume of Q Hayashida’s  MJ: This is a tricky pick for me, with nothing I’m really excited about shipping into Midtown Comics this week. With that in mind, I’m going to go completely off the list and get into the spirit of this week’s Manga Moveable Feast by recommending that everyone pick up something by

MJ: This is a tricky pick for me, with nothing I’m really excited about shipping into Midtown Comics this week. With that in mind, I’m going to go completely off the list and get into the spirit of this week’s Manga Moveable Feast by recommending that everyone pick up something by  DAVID: It might have escaped your notice, but our long, national nightmare is finally over, and the Eisner Awards have finally given a prize to Naoki Urasawa. After an enormous number of nominations, he won a 2011 Eisner for

DAVID: It might have escaped your notice, but our long, national nightmare is finally over, and the Eisner Awards have finally given a prize to Naoki Urasawa. After an enormous number of nominations, he won a 2011 Eisner for  KATE: After reading Bluewater’s unauthorized bio-comic of Lady Gaga, I’m morbidly curious about

KATE: After reading Bluewater’s unauthorized bio-comic of Lady Gaga, I’m morbidly curious about  MICHELLE Sometimes I feel like the only person who likes

MICHELLE Sometimes I feel like the only person who likes

First, I caught up to the end of

First, I caught up to the end of  Anyway, lest I work myself up into a froth over something I haven’t even read, I will instead relate my experience with the first volume of

Anyway, lest I work myself up into a froth over something I haven’t even read, I will instead relate my experience with the first volume of  My second game-based manga this week was the fourteenth volume of

My second game-based manga this week was the fourteenth volume of  MICHELLE: That does make me feel better. And speaking of disciplines in which long hours of practice pay off (hopefully) in a competitive realm, my final pick tonight is Takehiko Inoue’s

MICHELLE: That does make me feel better. And speaking of disciplines in which long hours of practice pay off (hopefully) in a competitive realm, my final pick tonight is Takehiko Inoue’s  MICHELLE: Although VIZ Media and others make a decent showing on this week’s release list from Midtown Comics, the majority of the titles hail from Yen Press. Unfortunately, most of them are the latest volumes in series I don’t personally follow, but there is one shining gem, the eighth volume of the quirky and fun manhwa,

MICHELLE: Although VIZ Media and others make a decent showing on this week’s release list from Midtown Comics, the majority of the titles hail from Yen Press. Unfortunately, most of them are the latest volumes in series I don’t personally follow, but there is one shining gem, the eighth volume of the quirky and fun manhwa,  SEAN: I already pimped Book Girl and the Captive Fool on my Manga The Week Of post, so will stop myself doing so again, even though it’s a fantastic novel series that everyone should be getting. Instead, I’ll go for the 4th and last of

SEAN: I already pimped Book Girl and the Captive Fool on my Manga The Week Of post, so will stop myself doing so again, even though it’s a fantastic novel series that everyone should be getting. Instead, I’ll go for the 4th and last of  doorstep. It’s just that charming. SangEun Lee has managed to create a heroine who really is just an “ordinary” girl, while reminding us how idiosyncratic and genuinely relatable “ordinary” can be. Also, as Michelle mentioned, it’s the first time ever I can recall actively ‘shipping someone with a cactus. I wholeheartedly recommend 13th Boy.

doorstep. It’s just that charming. SangEun Lee has managed to create a heroine who really is just an “ordinary” girl, while reminding us how idiosyncratic and genuinely relatable “ordinary” can be. Also, as Michelle mentioned, it’s the first time ever I can recall actively ‘shipping someone with a cactus. I wholeheartedly recommend 13th Boy. KATE: Though I also share the group’s enthusiasm for Blue Exorcist and 13th Boy, I’m going to recommend the latest omnibus of

KATE: Though I also share the group’s enthusiasm for Blue Exorcist and 13th Boy, I’m going to recommend the latest omnibus of

MICHELLE: Indeed I have! I decided to make it a CLAMP week, and first up is volume four of

MICHELLE: Indeed I have! I decided to make it a CLAMP week, and first up is volume four of  MJ: Well, earlier this week, I dug into the first issue of

MJ: Well, earlier this week, I dug into the first issue of  MICHELLE: My second CLAMP selection is the

MICHELLE: My second CLAMP selection is the  MJ: Well, It’s a bit of a strange one, or at least strange for me. While I’m used to receiving a variety of manga for review from Viz, I admit to being quite surprised when my latest review package contained volume one of

MJ: Well, It’s a bit of a strange one, or at least strange for me. While I’m used to receiving a variety of manga for review from Viz, I admit to being quite surprised when my latest review package contained volume one of

KATE: After last week’s meager offerings, this week’s new arrival list has something for everyone: robots, magical girls, hoop fanatics, mad surgeons, cross-dressing samurai. Though I’m looking forward to reading Tank Tankuro: The Pre-War Years, 1934-1935, my heart belongs to

KATE: After last week’s meager offerings, this week’s new arrival list has something for everyone: robots, magical girls, hoop fanatics, mad surgeons, cross-dressing samurai. Though I’m looking forward to reading Tank Tankuro: The Pre-War Years, 1934-1935, my heart belongs to  eighteen, which leaves me pretty worried for the fate of the series. This is not a case where releases have slowed down because we’ve caught up to Japan—volume 30 just came out there—but simply due to low sales. So, please check out Kaze Hikaru! Even if you think you don’t like shoujo.

eighteen, which leaves me pretty worried for the fate of the series. This is not a case where releases have slowed down because we’ve caught up to Japan—volume 30 just came out there—but simply due to low sales. So, please check out Kaze Hikaru! Even if you think you don’t like shoujo.